Zimbabwean dollar

However, the ESAP caused widespread poverty and unemployment, since many of the lost jobs depended on formerly-subsidised exports with reduced global demand.

[11][12]: 6–13 The widespread poverty and unemployment, combined with impromptu spending to support veterans of the Rhodesian Bush War, resulted in a major currency crash on 14 November 1997.

[13] The currency's official and parallel rates continued to plummet in the context in falling incomes from exports, the chaotic redistribution of land to inexperienced farmers, and Zimbabwe's involvement in the Second Congo War.

During the same month, the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe declared inflation illegal, outlawing any raise in prices on certain commodities between 1 March and 30 June 2007.

Officials arrested executives of some Zimbabwean companies for increasing prices on their products,[17][18] and economists reported that "chaos had started to reign and people in the public sector became frantic".

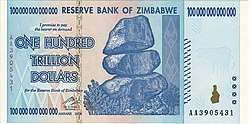

[26][27] Despite redenomination, the RBZ was forced to print banknotes of ever higher values to keep up with surging inflation, with ten zeros reappearing by the end of 2008.

[failed verification][34] Despite the introduction of the fourth dollar, however, the problems were not eliminated, and the economy continued to be almost completely dollarised.

[36] In late January 2009, acting Finance Minister Patrick Chinamasa announced that all Zimbabweans would be allowed to conduct business with any currency, as a response to the hyperinflation crisis.

[37] On 12 April 2009, media outlets reported that economic planning minister Elton Mangoma had announced the suspension of the local currency "for at least a year", effectively terminating the fourth dollar.

[38][39] All four issues of the Zimbabwean dollar experienced high rates of inflation, although it was not until the early 2000s that Zimbabwe started to experience completely unsustainable hyperinflation.

[47] The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe responded to the dwindling value of the dollar by repeatedly arranging the printing of further banknotes,[48][49][50][51][52] often at great expense from overseas suppliers.

[53][54] By late 2008, inflation had risen so high that automated teller machines for one major bank gave a "data overflow error" and stopped customers' attempts to withdraw money with so many zeros.

[56] It was reported that on 1 July 2008 the company's management board decided to cease delivering banknote paper to the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe with immediate effect.

The decision was in response to an "official request" from the German government and calls for international sanctions by the European Union and the United Nations.

[58] The move led to a sharp drop in the usage of the Zimbabwean dollar, as hyperinflation rendered even the highest denominations worthless.

On 29 January 2014, the Zimbabwe central bank announced that the US dollar, South African rand, Botswana pula, pound sterling, Euro, Australian dollar, Chinese yuan (renminbi), Indian rupee, and Japanese yen would all be accepted as legal currency within the country.

[61][62] This move was meant to stabilise the economy and establish a credible nominal anchor under low inflation conditions.

The exercise brought closure to the outstanding issue on the Zimbabwe dollar, further confirming the government's position that the local unit will not return anytime soon.

[63] Similar to the Iraqi dinar scam, some promoters claim that a future "revalue" (RV) event will cause Zimbabwe dollar notes to regain some nonzero fraction of their original value.

More detailed data can be found in the table below: 700 to 800 (8 September – high volume transactions);[70] 850 (14 September);[71] 1,200 to 1,300 (28 Sep) or 1,500 (29 September – high volume transactions)[72] 1,500 (12 October);[73] 1,700 (6 November);[74] 2,000 (19 November);[75] 2,400 (29 November);[76] 3,000 (25 December)[77] 3,200 (11th[78]); 3,500 (18th[79]); 4,000 (20th[80]); 4,200 (23rd[81]); 6,000 (26th[82]) 4,800 (2nd[83]); 5,000 (12th[84]); 6,600 (23rd[85]); 7,000 (27th[86]) 7,500 (1st[87]) 8,000 (2nd[88]); 10,000 (8th[89]); 11,000 (11th[90]); 12,000 – 17,500 (16th[91]); 16,000 (19th[92]); 20,000 (21st[93]); 24,000 (22nd[94]); 25,000 (27th[95]); 26,000 (29th[96]) 30,000 (1st[97]); 15,000 (7th[98]); 20,000 (8th[99]); 25,000 (11th[100]); 35,000 (15th[101]) 28,000 (10th[103]); 32,000 (18th[104]); 38,000 (20th[105]); 40,000 (22nd[106]); 45,000 (24th[107]); 50,000 (29th[108]) 55,000 (3rd[109]); 60,000 (12th[110]); 75–100,000 (13th[111]); 120,000 (16th[19]); 205,000 (20th[112]); 300,000 (22nd[113]); 400,000 (23rd[114]) 270,000 (5th[115]); 300,000 (14th[116]) 200,000 (21st[117]) 250,000 (7th[118]); 280,000 (14th[119]); 340,000 (18th[120]); 500,000 (26th[121]); 600,000 (29th[122]) 750,000 (17th[123]); 1,000,000 (19th[124]) 1,200,000 (1st[125]); 4,500,000 (14th[126]) (not confirmed); 1,400,000 (24th[127]); 1,500,000 (30th[128]) 1,800,000 (1st[129]); 4,000,000 (3rd[130]) 1,900,000 (3rd[131]); 2,000,000 (4th[132]); 3,000,000 (8th[133]); 4,500,000 (19th[134]); 5,000,000 (21st[134]); 6,000,000 (24th[135]) The Old Mutual Implied Rate (OMIR) is calculated by dividing the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange price of the Old Mutual share by the London Stock Exchange Price for the same share.

By 23 May 2008, Bloomberg[158] and Oanda[159] began publishing floating rates based on Zimbabwe's formally regulated domestic bank market, while Yahoo Finance started using the updated official rate in July, albeit with a decimal point shift of 6 places.

[160] On 3 October 2008, the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe temporarily suspended the Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) system, halting electronic parallel market transfers,[161] but it was reinstated on 13 November 2008.

ZSE chief executive Emmanuel Munyukwi revealed that a large number of multi-quad-, quin-, and sextillion cheques had bounced.

[191] 22.00 (3rd); 24.51 (4th) 28.54 (5th); 32.19 (6th) 35.34 (9th); 38.80 (10th) 42.32 (11th); 46.07 (12th) 49.87 (13th); 53.00 (16th) 58.04 (17th); 62.70 (18th) 66.49 (19th); 71.21 (20th) 76.22 (23rd); 81.58 (24th) 86.15 (25th); 91.39 (26th) 95.42 (27th) 300 (2nd)[30] 150,000 (3rd) 99.67 (2nd); 103.29 (3rd) 108.01 (4th); 113.12 (5th) 117.26 (6th); 121.85 (9th) 126.11 (10th); 131.00 (11th) 134.92 (12th); 138.58 (13th) 143.42 (16th); 150.52 (17th) 156.69 (18th); 163.34 (19th) 170.39 (20th); 177.25 (23rd) 186.61 (24th); 193.52 (25th) 199.76 (26th); 206.74 (27th) 209.62 (30th); 213.07 (31st) 221.29 (1st); 225.83 (2nd) 230.68 (3rd); 238.94 (6th) 244.81 (7th); 245.21 (8th) 249.40 (9th); 255.19 (14th) 259.10 (15th); 263.94 (16th) 266.64 (17th); 271.04 (20th) 294.18 (24th); 306.68 (29th) 309.31 (30th) 315.23 (4th); 319.13 (5th) 328.36 (6th); 320.02 (7th) 326.26 (8th); 329.65 (11th) 332.26 (12th); 336.46 (13th) 345.12 (14th); 350.30 (15th) 354.58 (19th); 357.48 (20th) 360.64 (21st); 363.14 (22nd) 363.48 (16th) 371.39 (16th) 361.62 (28th) Shortly after the Zimbabwean dollar was discontinued, they were purchased as curiosities, or in quantity as novelty gifts, for example to financial advisers' clients to show why they should invest in diverse assets instead of cash, which loses its value over the long term.