Economy of Zimbabwe

The new occupants, mainly consisting of indigenous citizens and several prominent members of the ruling ZANU-PF administration, were inexperienced or uninterested in farming, thereby failing to retain the labour-intensive, highly efficient management of previous landowners.

The contemporary lack of agricultural expertise triggered severe export losses and negatively affected market confidence.

The country has experienced a massive drop in food production and idle land is now being utilised by rural communities practising subsistence farming.

Production of staple foodstuffs, such as maize, has recovered accordingly – unlike typical export crops including tobacco and coffee.

[32] Uncertainty around the indigenisation programme (compulsory acquisition), the perceived lack of a free press, the possibility of abandoning the US dollar as official currency, and political uncertainty following the end of the government of national unity with the MDC as well as power struggles within ZANU-PF have increased concerns that the country's economic situation could further deteriorate.

Land in Zimbabwe was forcibly seized from white farmers and redistributed to black settlers, justified by Mugabe on the grounds that it was meant to rectify inequalities left over from colonialism.

[53] As other southern African countries, Zimbabwean soil is rich in raw materials, namely platinum,[54] coal, iron ore, and gold.

[58] This followed former South African President Thabo Mbeki’s warning days earlier that Zimbabwe needed to stop its "predatory elite" from colluding with mining companies for their own benefit.

Despite poor infrastructure and a lack of both human and financial resources, biotechnology research is better established in Zimbabwe than in most sub-Saharan countries, even if it tends to use primarily traditional techniques.

As the intensity of the strikes grew, the government was forced to pay the war veterans a once-off gratuity of ZWD $50,000 by December 31, 1997, and a monthly pension of US$2,000 beginning January 1998 (Kanyenze 2004).

Many interventionist moves were undertaken to try to reverse some of the negative effects of the Structural Adjustment Programs and to try to strengthen the private sector that was suffering from decreasing output and increasing competition from cheap imported products.

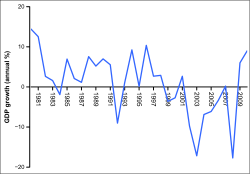

[27] Following the Lancaster House Agreement in December 1979, the transition to majority rule in early 1980, and the lifting of sanctions, Zimbabwe enjoyed a brisk economic recovery.

However, depressed foreign demand for the country's mineral exports and the onset of a drought cut sharply into the growth rate in 1982, 1983, and 1984.

However, it slumped in 1986 to a zero growth rate and registered a negative of about 3% in 1987, primarily because of drought and the foreign exchange crisis faced by the country.

Many western countries argue that the Government of Zimbabwe's land reform program, recurrent interference with, and intimidation of the judiciary, as well as maintenance of unrealistic price controls and exchange rates has led to a sharp drop in investor confidence.

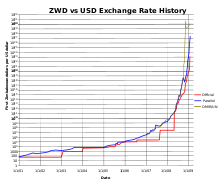

Between 2000 and December 2007, the national economy contracted by as much as 40%; inflation vaulted to over 66,000%, and there were persistent shortages of hard currency, fuel, medicine, and food.

[76] [citation needed] The Mugabe Government attribute Zimbabwe's economic difficulties to sanctions imposed by the Western powers.

that the sanctions imposed by Britain, the US, and the EU have been designed to cripple the economy and the conditions of the Zimbabwean people in an attempt to overthrow President Mugabe's government.

Terms of the sanctions made it such that all economic assistance would be structured in support of "democratisation, respect for human rights and the rule of law."

[78] As of February 2004, Zimbabwe's foreign debt repayments ceased, resulting in compulsory suspension from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

In December 2005 Zimbabwe made a mystery loan repayment of US$120 million to the International Monetary Fund due to expulsion threat from IMF.

On 30 July 2008, the Governor of the RBZ, Gideon Gono announced that the Zimbabwe dollar would be redenominated by removing 10 zeroes, with effect from 1 August 2008.

Dollarization also had other consequences, including: In January, 2013 Finance Minister Tendai Biti announced that Zimbabwe's national public account held just $217.

"[94] In August 2014, Zimbabwe began selling treasury bills and bonds to pay public sector salaries that have been delayed as GDP growth weakens while the economy experiences deflation.

Despite serious internal differences this government made some important decisions that improved the general economic situation, first of all the suspension of the national currency, the Zimbabwean Dollar, in April 2009.

That stopped hyperinflation and made normal forms of business possible again, by using foreign currency such as the US American Dollar, the South African Rand, the EUs Euro or the Botswana Pula.

Although legislation dealing with the indigenisation of the Zimbabwean economy has been in development since 2007 and actively initiated by ZANU-PF in 2010 the policy has continued to be accused of being unclear and a form of "racketeering by regulation.

[109] This prompted the Zimbabwean government to limit cash withdrawals from banks and change exchange-control regulations in order to try to promote exports and reduce the currency shortage.

[109][110] In June and July 2016, after Government employees had not been paid for weeks, police had set up road blocks to coerce money out of tourists and there were protests throughout Zimbabwe,[111][112] Patrick Chinamasa, the finance minister, toured Europe in an effort to raise investment capital and loans, admitting "Right now we have nothing.

[114][115] In mid-July 2019 inflation had increased to 175% following the adoption of a new Zimbabwe dollar and banning the use of foreign currency thereby sparking fresh concerns that the country was entering a new period of hyperinflation.