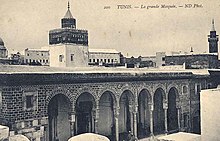

Al-Zaytuna Mosque

[2] Ibn 'Arafa, a major Maliki scholar, al-Maziri, the great traditionalist and jurist, and Aboul-Qacem Echebbi, a famous Tunisian poet, all taught there, among others.

[citation needed] Another account, transmitted by the 17th century Tunisian historian Ibn Abi Dinar,[3] reports the presence of a Byzantine Christian church dedicated to Santa Olivia at that location.

[2][3] Archeological investigations and restoration works in 1969–1970 have shown that the mosque was built over an existing Byzantine-era building with columns, covering a cemetery.

[3] A more recent interpretation by Muhammad al-Badji Ibn Mami suggests that the previous structures may have been part of a Byzantine fortification, inside which the Arab conquerors built their mosque.

[6] The saint is particularly venerated in Tunisia because it is superstitiously thought that if the site and its memory are profaned then a misfortune will happen; this includes a belief that when her relics are recovered Islam will end.

[8] In 1402 king Martin I of Sicily requested the return of Saint Olivia's relics from the Berber Caliph of Ifriqiya Abu Faris Abd al-Aziz II, who refused him.

The 11th-century writer Al-Bakri wrote that Ubayd Allah ibn al-Habhab, the Umayyad governor of Ifriqiya, built a Friday mosque (jāmīʿ) in Tunis in 114 Hijri (732–733 CE).

[4] However, al-Bakri also mentions a mosque (masjid) being built by Hasan ibn al-Nu'man, who led the conquest of Carthage, in 79 Hijri (circa 698 CE).

[4] Lucien Golvin, a 20th-century French scholar, argued that Ibn al-Habhab was the founder but that the construction took place in 116 Hijri (734–735 CE).

[13] The mosque owes its current overall form to a reconstruction under the Aghlabids, the dynasty that ruled Ifriqiya on behalf of the Abbasid caliphs in the 9th century.

[14]: 38–41 A contemporary inscription at the base of the dome in front of the mihrab gives the date of this construction and names three individuals: 1) the Abbasid caliph al-Musta'in Billah, identified as the main patron;[6] 2) Nusayr, a mawla of the caliph and probably the overseer of the works;[6] and 3) Fathallah or Fath al-Banna', the architect and chief builder.

[14]: 86–87 [6] The dates for these works are provided by a series of inscriptions around the Qubbat al-Bahu, but the names of the patrons themselves were erased at a later period,[6] possibly when the Zirids declared independence from the Fatimids in the 11th century.

[2] Significant restoration work was carried out by the Hafsid rulers, under al-Mustansir in 1250 and under Abu Yahya Zakariya in the early 14th century, adding features such as ablution facilities and replacing some of the woodwork.

[2][6] Its appearance is known from old photographs: it had a cuboid shape (having a shaft with a square base) and was crowned with an arcaded gallery and a polygonal turret or lantern at its summit.

[15] This shift in power helped al-Zaytuna to flourish and become one of the major centres of Islamic learning, and Ibn Khaldun, the first social historian in history was one of its products.

Along with disciplines theology – such as exegesis of the Qur'an (tafsir) – the university taught fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), Arabic grammar, history, science and medicine.

The manuscripts covered almost all subjects and sciences, including grammar, logic, documentations, etiquette of research, cosmology, arithmetic, geometry, minerals, vocational training, etc.

In 1896 new courses were introduced such as physics, political economy, and French, and in 1912 these reforms were extended to the university's other branches in Kairouan, Sousse, Tozeur, and Gafsa.

Some prominent members of the Algerian nationalist movement studied here, such as 'Abd al-Hamid ibn Badis, Tawfiq Madani, and Houari Boumédiène.

[14]: 39–40, 220 The adjoining rooms and structures around the rest of the mosque's perimeter include shops, libraries, and maqsuras (areas reserved for specific individuals or groups during prayer).

The ornamentation includes carved moldings, decorative blind arches and niches, pilasters, and polychrome mosaic or ablaq stonework in red, white, and black stone.

[6] The hypostyle prayer hall is divided into 15 aisles by rows of columns, 6 bays long, supporting horseshoe arches running perpendicular to the southeastern qibla wall.

[6] Inside the mihrab is a marble plaque covered in gold leaf and carved with an Aghlabid Kufic inscription with religious formulas such as the shahada.