City Investing Building

The bulk of the building was 26 stories high above Church Street and was capped by a seven-story central portion with gable roofs.

The narrowness of the gap was a result of a design choice by the Singer's architect, Ernest Flagg.

The stonework came from William Bradley & Sons; the ornamental ironwork from Hecla Iron Works; the terracotta and other tilework from the National Fireproofing Company; the plumbing from Wells and Newton; and the marble work from J. H. Shipway and Bros.[15] The City Investing Building's facade was divided into three horizontal sections: a base with four stories and a raised basement; a shaft with 21 stories and a full-height cornice; and a capital with six stories and an attic.

[8][17] The Real Estate Record and Guide described the building as rising 33 stories, as counted from Church Street, but excluding the attic.

[19] The City Investing Building was largely shaped in an "F", with the two northward "prongs" of the "F" flanking a 40-by-65-foot (12 by 20 m) light court on Cortlandt Street.

[3] The central section of the building, recessed from the light court on Cortlandt Street, rose six additional stories into the capital, with an ornate gable roof made of copper.

[3] The five-story base was clad with light stone, while the shaft and capital were decorated with white brick and terracotta.

The fourth floor was topped by a large cornice that was at the same level as the roof of the six-story Gilsey Building.

[3] Robert E. Dowling, the building's developer, hired Vincenzo Alfano to design sculptural groups for the facade.

[8][15] As completed, the building used 9.1 million bricks, 25,000 lighting fixtures, 3,000 short tons (2,700 long tons; 2,700 t) of terracotta, about 2,600,000 square feet (240,000 m2) of plaster, about 1,870,000 square feet (174,000 m2) of hollow tile, 8,170,000 pounds (3,710,000 kg) of marble, and about 21.8 million mosaic cubes.

Also included in the building was many miles of plumbing, steam piping, wood base, picture molding, conduits, and electrical wiring.

[3] The floors consisted of hollow-tile flat arches or concrete with cinder filling, and were surfaced with mosaic or terrazzo tiles.

The south wall was generally 32 inches (810 mm) thick at the base, tapering to 12 feet (3.7 m) just below the 25th floor.

Sections of the masonry basement floors from the previous buildings on the site were also removed in the process.

[8] The caissons supported foundation piers that were topped by plates with grillages of transversely laid I-beams.

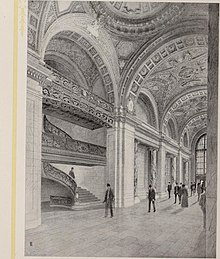

[32] The entrance arch on Broadway led to a limestone vestibule about 30 feet (9.1 m) deep, which contained the main doors.

[10] The upper floors typically had a west–east elevator hallway along the southern wall, with the other areas being used for rental space.

[17] A 32,000-square-foot (3,000 m2) cellar extended under the Broadway sidewalk, and contained the building's boiler room.

[15] The elevators were placed in three banks the south side of the building, along the section facing the Singer Tower.

[4][10] The City Investing Company bought the Coal and Iron Exchange Building[c] at Church and Cortlandt Streets in January 1906.

[42] The next month, there circulated rumors that the City Investing Building would rise to 39 stories—one less than the Singer Tower to the south, which was simultaneously being erected as the world's tallest building—but this modification did not happen.

The Coal and Iron Exchange Building took five months to destroy, because of the extremely thick materials it used; it was demolished by October 1906,[44] although its cornerstone was not retrieved until June 1907.

Hoisting engines were installed to place the beams for the foundation, while the piers were sunk into the ground under their own weight.

[12] In December 1919, London banker Grigori Benenson bought the City Investing Building for $10 million in cash.

[53] During the 1920s, the Benenson Building gained tenants such as the Chemical Bank[54] and advertising agency Albert Frank & Company.

[55] Benenson also brought adjacent property to the north, intending to construct a supertall skyscraper on the site, but these plans were canceled due to the Wall Street Crash of 1929.

[56] Benenson's company suffered financially from the Wall Street Crash and defaulted on its mortgages in the years afterward.

[64][65] 165 Broadway, the Gilsey Building, and 99 Liberty Street were sold in 1947 to N. K. Winston and George Gregory for $11 million.

[75] The situation led to New York City's 1916 Zoning Resolution, which required buildings to be set back above a certain height.

[6][30] Photographs of the building almost always showed its northern side on Cortlandt Street because its primary elevation to the east along Broadway was excessively narrow.