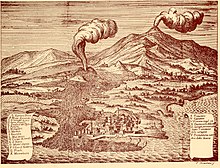

1669 eruption of Mount Etna

After several weeks of increasing seismic activity that damaged the town of Nicolosi and other settlements, an eruption fissure opened on the southeastern flank of Etna during the night of 10–11 March.

Several more fissures became active during 11 March, erupting pyroclastics and tephra that fell over Sicily and accumulated to form the Monti Rossi scoria cone.

Lava disgorged from the eruption fissures flowed southwards away from the vent, burying a number of towns and farmland during March and April, eventually covering 37–40 square kilometres (14–15 sq mi).

News of the eruption spread as far as North America and a number of contemporaries described the event, leading to an increased interest in Etna's volcanic activity.

[3] Etna is one of the most iconic and active volcanoes in the world; its eruptions–including both effusive and explosive eruptions from flank and central vents–have been recorded for 2,700 years.

[16] Early activity that lasted until 9 March reflects the ascent of deep magma within the mountain while subsequent earthquakes were associated with the opening of the eruption fissure.

[17] After midnight on 11 March, the first fissure opened up on Etna[1] between the Monte Frumento Supino cinder cone[18] and Piano San Leo.

During the afternoon of the same day, a second fissure opened and erupted lithics and ash clouds; historical records vary on the number of vents that became active.

[1] An alternative reconstruction of events envisages the development of several fissure segments between 950–700 m (3,120–2,300 ft) elevation, most of which underwent brief explosive and effusive eruptions.

[20] At 18:30, the main vent became active and lava began to flow from the second fissure[13] from east of the Monte Salazara cone,[1] close to Nicolosi,[21] at 800–850 m (2,620–2,790 ft) elevation[13] in Etna's southern rift zone.

[26] These deposits reached a thickness of 12 centimetres (4.7 in) 5 km (3.1 miles) from the vent;[27] roofs in Acireale,[1] Pedara, Trecastagni and Viagrande collapsed under the weight of the tephra.

This sulfur may have risen into the upper troposphere, causing changes in the chemistry of the regional atmosphere and environmental hazards.

[20] Almost a century after the eruption, Sir William Hamilton reported the lava flows had shifted an otherwise undamaged vineyard by over 0.5 km (0.31 miles).

[38] The southeastern branch of the flow, which was fed by lava tubes and ephemeral vents, continued to advance and destroyed farms close to Catania.

[44] Beginning on 30 April,[40][45] some flows overtopped the walls[24] and penetrated Catania, pushing aside weaker buildings and burying sturdier ones[46] but did not cause much damage.

Authorities in Catania requested assistance from the then-viceroy of Sicily Francisco Fernández de la Cueva, 8th Duke of Alburquerque and took care of about 20,000 refugees.

[54] These refugees sought out the city as a safe haven because it was distant from the eruption at that time and they were received with great hospitality.

[62] Fifty inhabitants of Pedara led by priest Diego Pappalardo[11] attempted to divert a lava flow by breaking up the margins with axes and picks while protecting themselves from the heat through water-soaked hides.

This effort worked initially until 500 inhabitants of Paternò put a stop to it because their town was threatened by the redirected lava flow.

[65] There were religious objections to diverting lava flows; such an intervention was viewed as sacrilegious in the context of the relationship between God, man, and nature.

[13] The 1669 eruption has been defined as the starting point of a century-long cycle of activity that continues to this day[76] and Etna's volcanic products are subdivided into pre-1669 and post-1669 formations in Italy's geological map.

[14] Approximately fourteen[85] villages and towns[g] were destroyed by the lava flows or by earthquakes that preceded and accompanied the eruption.

[35][h] South of the volcano, ash and tephra fallout destroyed large but unclearly stated quantities of olive groves, orchards, pasture, vineyards, and mulberry trees that were used for silkworm rearing.

[14][89][90] Contrary to common reports, not all of Catania was destroyed[45] but its outskirts,[55][i] and the western part of the city sustained damage.

[95] The reconstruction costs, damages caused by the eruption,[88] and a population decrease during the events depressed both industrial and commercial activity in the city.

[97] The noted Canary Islands poet Juan Bautista Poggio y Monteverde may have drawn inspiration from the eruption.

[111] Lava was used to pave roads, for constructions, and later for architectural elements, the production of bituminous conglomerate, concrete, and statues[21] such as the Fountain of the Elephant in Catania.

[124] Italian scientist Giovanni Alfonso Borelli (1608–1679) in his 1670 publication Historia et Meteorologia and the British ambassador in Constantinople Heneage Finch, 3rd Earl of Winchilsea (1628–1689) in a report to King Charles II of England[l] wrote about the eruption.

Aetna, 1669, communicated by some inquisitive merchants now residing in Sicily and A chronological account of several Incendiums or fires of Mt.

[126] Apart from the lava, tephra and lapilli associated with explosive activity would damage critical infrastructure close to the vent,[2] disrupt air travel, and impact both human health and the environment.