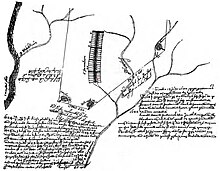

1688 Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery

After training as an attorney, Pastorius sought spiritual release from his lucrative but uninspiring practice with the local gentry, and he turned inward looking for a philosophical purity in his life.

He was attracted to Penn's colony as a place where religious freedom would allow him to start afresh a life free from "libertinism and sins of the European world".

Meanwhile, the Mennonites and Quakers in the Netherlands and along the Rhine Valley were often fined or imprisoned for publicly practicing a faith other than the officially recognized Calvinism, Catholicism, and Lutheranism.

He arrived in 1682, had the land surveyed, organized Philadelphia as a welcoming town laid out as a grid with many green spaces, and profited by selling lots.

In October, 1683, thirteen German-Dutch families from Krefeld in the Rhine Valley, including the Op den Graeffs, arrived with their own land claim.

As it turned out, the people from the Frankfurt Company never emigrated to the new colony, but more Quakers and Mennonites came from the Rhine valley and Pastorius's ambitious plan for a German-speaking town near Philadelphia grew and became real.

William Penn oversaw the economic progress of his colony and once proudly declared that during the course of a year Philadelphia had received ten slave ships.

The first settlers of Germantown were soon joined by several more Quaker and Mennonite families from Kriegsheim (Monsheim), also in the Rhine valley, who were ethnic Germans but spoke a similar dialect to the Hollanders from Krefeld.

The German-Dutch settlers were unaccustomed to owning slaves, although from the shortage of labor they understood why slavery was required to ensure the economic prosperity of the colony.

The men gathered at Thones Kunders's house and wrote a petition based upon the Bible's Golden Rule, "Do unto others as you would have them do unto you", urging the meeting to abolish slavery.

They emphatically argue that in their society the capture and sale of ordinary people as slaves, where husband, wife and children are separated, would not be tolerated, again referring to the Golden Rule.

The four men also assert that according to the Golden Rule, the slaves would have the right to revolt, and that inviting more people to the new land would be difficult if prospective settlers saw the contradiction inherent in slavery.

In mentioning the possibility of a slave revolt, they clearly were suggesting to that slavery would discourage potential settlers from emigrating to the American colonies.

First, the petition's grammar seems unusual today but reflects the Krefelders' incomplete knowledge of English as well as typical pre-modern use of variable spelling.

The four men were referring to the widely known stories of Barbary pirates who had established outposts on the coast of North Africa and for hundreds of years had plundered ships.

Some English, French, and Germans were allowed to pay their way out of slavery and so brought back the stories of marauding pirates capturing slaves.

The widely circulated stories of slavery on the Barbary Coast were true, for Europeans had been the prey of political enemies and renegades who had captured them as slaves.

Indeed, in the year that the petition was written, a number of Quakers were enslaved in Morocco, including the captain of the ship that had brought Pastorius and his compatriots to Pennsylvania.

The four men - Pastorius, Garret Hendericks, and both Op den Graeff brothers - presented their petition at the local monthly meeting at Dublin (Abington), but it is not clear what they expected to happen.

[3] Although they were accepted in the Quaker community, they were outsiders who could not speak or write fluently in English, and they also had a fresh view of slavery that was unique to Germantown.

Realizing that the abolition of slavery would have a wide and overreaching impact on the entire colony, none of the meetings wanted to pass judgment on such a "weighty matter".

Germantown continued to prosper, growing in population and economic strength, becoming widely known for the quality of its products such as paper and woven cloth.

Villages were setup in places such as Lima, Pennsylvania, where released slaves could settle with support from local families involved in the anti-slavery movement.

[7][8] It compelled a higher standard of reasoning about fairness and equality that continued to grow in Pennsylvania and the other colonies with the Declaration of Independence and the abolitionist and suffrage movements, eventually giving rise to Abraham Lincoln's reference to human rights in the Gettysburg Address.

At that time, it was in deteriorating condition, with tears at the edges, paper tape covering voids and handwriting where the petition had originally been folded, and its oak gall ink slowly fading into gray.

CCAHA conservator Morgan Zinsmeister removed previous repairs and reduced centuries of old and discolored adhesives with various poultices and enzymatic solutions.

The petition was shown at an exhibit of original rare American documents at the National Constitution Center on Independence Mall in the summer of 2007.