July Revolution

It led to the overthrow of King Charles X, the French Bourbon monarch, and the ascent of his cousin Louis Philippe, Duke of Orléans.

Although France was considered an enemy state, Talleyrand was allowed to attend the Congress because he claimed that he had only cooperated with Napoleon under duress.

The causes of this dramatic shift in public opinion were many, but the main two were: Critics of the first accused the king and his new ministry of pandering to the Catholic Church, and by so doing of violating guarantees of equality of religious belief as specified in the Charter of 1814.

Since the restoration of the monarchy, there had been demands from all groups to settle matters of property ownership in order to reduce, if not eliminate, the uncertainties in the real estate market.

On 12 April, propelled by both genuine conviction and the spirit of independence, the Chamber of Deputies roundly rejected the government's proposal to change the inheritance laws.

[clarification needed] The popular newspaper Le Constitutionnel pronounced this refusal "a victory over the forces of counter-revolutionaries and reactionism.

Charles X "later told [his cousin] Orléans that, 'although most people present were not too hostile, some looked at times with terrible expressions'.

On 30 April, on the grounds that it had behaved in an offensive manner towards the crown, the king abruptly dissolved the National Guard of Paris, a voluntary group of citizens formerly considered a reliable conduit between the monarchy and the people.

During this time, the liberals championed the "221" as popular heroes, while the government struggled to gain support across the country, as prefects were shuffled around the departments of France.

The elections that followed, taking place between 5 and 19 July 1830, returned a narrow majority for Polignac and his Ultra-royalists, but many Chamber members were nevertheless hostile to the king.

On Tuesday 27 July, a revolution began in earnest Les trois journées de juillet, and ultimately ended the Bourbon monarchy.

[7] That evening, when police raided a news press and seized contraband newspapers, they were greeted by a sweltering, unemployed mob angrily shouting, "À bas les Bourbons!"

Armand Carrel, a journalist, wrote in the next day's edition of Le National: France... falls back into revolution by the act of the government itself... the legal regime is now interrupted, that of force has begun... in the situation in which we are now placed obedience has ceased to be a duty...

can be heard....[12]Charles X ordered Maréchal Auguste Marmont, Duke of Ragusa, the on-duty Major-General of the Garde Royale, to repress the disturbances.

Marmont was personally liberal, and opposed to the ministry's policy, but was bound tightly to the King because he believed such to be his duty; and possibly because of his unpopularity for his generally perceived and widely criticized desertion of Napoleon in 1814.

[page needed] The king remained at Saint-Cloud, but was kept abreast of the events in Paris by his ministers, who insisted that the troubles would end as soon as the rioters ran out of ammunition.

The Garde Royale was mostly loyal for the moment, but the attached line units were wavering: a small but growing number of troops were deserting; some merely slipping away, others leaving, not caring who saw them.

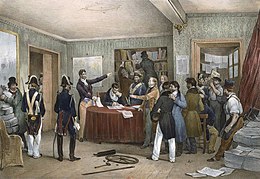

In Paris, a committee of the Bourbon opposition, composed of banker-and-kingmaker Jacques Laffitte, Casimir Perier, Generals Étienne Gérard and Georges Mouton, comte de Lobau, among others, had drawn up and signed a petition in which they asked for the ordonnances to be withdrawn.

[13] After signing the petition, committee members went directly to Marmont to beg for an end to the bloodshed, and to plead with him to become a mediator between Saint-Cloud and Paris.

Discouraged but not despairing, the party then sought out the king's chief minister, de Polignac – "Jeanne d'Arc en culottes".

[page needed] Like Marmont, he knew that Charles X considered the ordonnances vital to the safety and dignity of the throne of France.

"They (the king and ministers) do not come to Paris", wrote the poet, novelist and playwright Alfred de Vigny, "people are dying for them ... Not one prince has appeared.

Marmont lacked either the initiative or the presence of mind to call for additional troops from Saint-Denis, Vincennes, Lunéville, or Saint-Omer; neither did he ask for help from reservists or those Parisians still loyal to Charles X.

A man wearing a ball dress belonging to the duchesse de Berry, the king's widowed daughter in law and the mother of the heir to the throne, with feathers and flowers in his hair, screamed from a palace window: 'Je reçois!

The amount of looting during these three days was surprisingly small[citation needed]; not only at the Louvre—whose paintings and objets d'art were protected by the crowd—but the Tuileries, the Palais de Justice, the Archbishop's Palace, and other places as well.

The July Column, located on Place de la Bastille, commemorates the events of the Three Glorious Days.

Two years later, Parisian republicans, disillusioned by the outcome and underlying motives of the uprising, revolted in an event known as the June Rebellion.

Although the insurrection was crushed within less than a week, the July Monarchy remained doubtfully popular, disliked for different reasons by both Right and Left, and was eventually overthrown in 1848.