1860 United States presidential election

From the mid-1850s, the anti-slavery Republican Party became a major political force, driven by Northern voter opposition to the Kansas–Nebraska Act and the Supreme Court's 1857 decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford.

A group of former Whigs and Know Nothings formed the Constitutional Union Party, which sought to avoid disunion by resolving divisions over slavery with some new compromise.

The 1860 Constitutional Union Convention, which hoped to avoid the slavery issue entirely, nominated a ticket led by former Tennessee Senator John Bell.

[3][4] The American Civil War began less than two months after Lincoln's inauguration, with the Battle of Fort Sumter; afterwards four further states seceded.

[5] The conservative Bates was an unlikely candidate but found support from Horace Greeley, who sought any chance to defeat Seward, with whom he now had a bitter feud.

He gained great notability with his acclaimed February 1860 Cooper Union speech, which may have ensured him the nomination although he had not yet announced his intention to run.

Lincoln's combination of a moderate stance on slavery, long support for economic issues, his western origins, and strong oratory proved to be exactly what the delegates wanted in a president.

The platform promised tariffs protecting industry and workers, a Homestead Act granting free farmland in the West to settlers, and the funding of a transcontinental railroad.

There was no mention of Mormonism (which had been condemned in the Party's 1856 platform), the Fugitive Slave Act, personal liberty laws, or the Dred Scott decision.

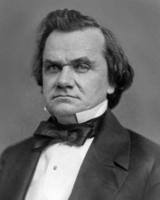

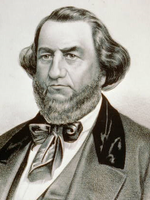

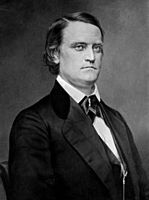

Six candidates were running: Stephen A. Douglas from Illinois, James Guthrie from Kentucky, Robert Mercer Taliaferro Hunter from Virginia, Joseph Lane from Oregon, Daniel S. Dickinson from New York, and Andrew Johnson from Tennessee, while three other candidates, Isaac Toucey from Connecticut, James Pearce from Maryland, and Jefferson Davis from Mississippi (the future president of the Confederate States) also received votes.

Douglas, a moderate on the slavery issue who favored "popular sovereignty", was ahead on the first ballot, but was 56½ votes short of securing the nomination.

[18] They met in the Eastside District Courthouse of Baltimore and nominated John Bell from Tennessee for president over Governor Sam Houston of Texas on the second ballot.

Gerrit Smith, a prominent abolitionist and the 1848 presidential nominee of the original Liberty Party, had sent a letter in which he stated that his health had been so poor that he had not been able to be away from home since 1858.

[22] In Ohio, Illinois, and Indiana, slates of presidential electors pledged to Smith and McFarland ran with the name of the Union Party.

On April 20, 1860, the party held what it termed a national convention to nominate Houston for president on the San Jacinto Battlefield in Texas.

Nonetheless, loyal army officers in Virginia, Kansas and South Carolina warned Lincoln of military preparations to the contrary.

However, historian Bruce Chadwick observes that Lincoln and his advisors ignored the widespread alarms and threats of secession as mere election trickery.

In three of the seven Deep South states, unionists (Bell and Douglas) won divided majorities in Georgia and Louisiana and neared it in Alabama.

[f] The four states that were admitted to the Confederacy after Fort Sumter held almost half its population, and voted a narrow combined majority of 53 percent for the pro-union candidates.

In the eleven states that would later declare their secession from the Union and be controlled by Confederate armies, ballots for Lincoln were cast only in Virginia,[g] where he received 1,929 votes (1.15 percent of the total).

Of the 97 votes cast for Lincoln in the state's post-1863 boundaries, 93 were polled in four counties along the Potomac River and four were tallied in the coastal city of Portsmouth.

In theory, any document containing a valid or at least non-excessive number names of citizens of a particular state (provided they were eligible to vote in the electoral college within that state) might have been accepted as a valid presidential ballot; however, what this meant in practice was that a candidate's campaign was responsible for printing and distributing their own ballots (this service was typically done by supportive newspaper publishers).

The election was held on Tuesday, November 6, 1860, and was noteworthy for the exaggerated sectionalism and voter enthusiasm in a country that was soon to dissolve into civil war.

In a similar divide between North and South electors, Breckenridge carried nine of the ten states that withheld Lincoln from the ballot, the exception being Tennessee.

[36] Lincoln's strategy was deliberately focused, in collaboration with Republican Party Chairman Thurlow Weed, on expanding on the states Frémont won four years earlier: New York was critical with 35 Electoral College votes, 11.5 percent of the total, and with Pennsylvania (27) and Ohio (23) as well, a candidate could collect 85 votes, whereas 152 were required to win.

If the President (and, by extension, the appointed federal officials in the South, such as district attorneys, marshals, postmasters, and judges) opposed slavery, it might collapse.

(The noted secessionist William Lowndes Yancey, speaking at New York's Cooper Institute in October 1860, asserted that with abolitionists in power, "Emissaries will percolate between master [and] slave as water between the crevices of rocks underground.

"[48]) Less radical Southerners thought that with Northern antislavery dominance of the federal government, slavery would eventually be abolished, regardless of present constitutional limits.

However, the "conditional Unionists" also hoped that when faced with secession, Northerners would stifle anti-slavery rhetoric and accept pro-slavery rules for the territories.

Nearly all "conditional Unionists" joined the secessionists, including for example presidential candidate John Bell of the Constitutional Union Party, whose home state of Tennessee was the last to secede.