Andrew Johnson

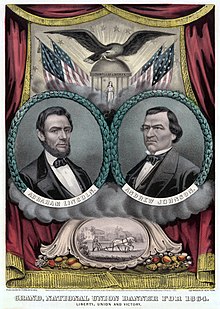

In 1864, Johnson was a logical choice as running mate for Lincoln, who wished to send a message of national unity in his re-election campaign, and became vice president after a victorious election in 1864.

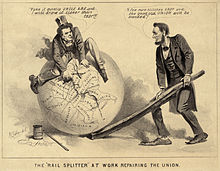

Johnson implemented his own form of Presidential Reconstruction, a series of proclamations directing the seceded states to hold conventions and elections to reform their civil governments.

He engaged in a number of political maneuvers to gain Democratic support, including the displacement of the Whig postmaster in Greeneville, and defeated Jonesborough lawyer John A. Aiken by 5,495 votes to 4,892.

In his first biennial speech, Johnson urged simplification of the state judicial system, abolition of the Bank of Tennessee, and establishment of an agency to provide uniformity in weights and measures; the last was passed.

[76][77] In 1859, it failed on a procedural vote when Vice President Breckinridge broke a tie against the bill, and in 1860, a watered-down version passed both houses, only to be vetoed by Buchanan at the urging of Southerners.

His successor as governor, Isham G. Harris, and the legislature organized a referendum on whether to have a constitutional convention to authorize secession; when that failed, they put the question of leaving the Union to a popular vote.

Although some argued that civil government should simply resume once the Confederates were defeated in an area, Lincoln chose to use his power as commander in chief to appoint military governors over Union-controlled Southern regions.

Johnson, once he was told by reporters the likely purpose of Sickles' visit, was active on his own behalf, delivering speeches and having his political friends work behind the scenes to boost his candidacy.

"[107] When word reached Nashville, a crowd assembled and the military governor obliged with a speech contending his selection as a Southerner meant that the rebel states had not actually left the Union.

[108] Now Vice President-elect, Johnson was eager to complete the work of reestablishing civilian government in Tennessee, although the timetable for the election of a new governor did not allow it to take place until after Inauguration Day, March 4.

Johnson's third priority was election in his own right in 1868, a feat no one who had succeeded a deceased president had managed to accomplish, attempting to secure a Democratic anti-Congressional Reconstruction coalition in the South.

[129] As Southern states began the process of forming governments, Johnson's policies received considerable public support in the North, which he took as unconditional backing for quick reinstatement of the South.

[138][139] When called upon by the crowd to say who they were, Johnson named Pennsylvania Congressman Thaddeus Stevens, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, and abolitionist Wendell Phillips, and accused them of plotting his assassination.

The trip, including speeches in Chicago, St. Louis, Indianapolis, and Columbus, proved politically disastrous, with the President making controversial comparisons between himself and Jesus, and engaging in arguments with hecklers.

Also on March 2, Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act over the President's veto, in response to statements during the Swing Around the Circle that he planned to fire Cabinet secretaries who did not agree with him.

With Congress in recess until November, Johnson decided to fire Stanton and relieve one of the military commanders, General Philip Sheridan, who had dismissed the governor of Texas and installed a replacement with little popular support.

[156] Johnson then suspended him pending the next meeting of Congress as permitted under the Tenure of Office Act; Grant agreed to serve as temporary replacement while continuing to lead the Army.

No seats in Congress were directly elected in the polling, but the Democrats took control of the Ohio General Assembly, allowing them to defeat for reelection one of Johnson's strongest opponents, Senator Benjamin Wade.

After the loss of the Crimean War in the 1850s, the Russian government saw its North American colony (today Alaska) as a financial liability, and feared losing control to Britain whose troops would easily swoop in and annex the territory from neighboring Canada in any future conflict.

When the President was slow to officially report ratifications of the Fourteenth Amendment by the new Southern legislatures, Congress passed a bill, again over his veto, requiring him to do so within ten days of receipt.

He also issued, in his final months in office, pardons for crimes, including one for Dr. Samuel Mudd, controversially convicted of involvement in the Lincoln assassination (he had set Booth's broken leg) and imprisoned in Fort Jefferson on Florida's Dry Tortugas.

Despite an effort by Seward to prompt a change of mind, he spent the morning of March 4 finishing last-minute business, and then shortly after noon rode from the White House to the home of a friend.

[200] In 1872, there was a special election for an at-large congressional seat for Tennessee; Johnson initially sought the Democratic nomination, but when he saw that it would go to former Confederate general Benjamin F. Cheatham, decided to run as an independent.

Memoirs from Northerners who had dealt with him, such as former vice president Henry Wilson and Maine Senator James G. Blaine, depicted him as an obstinate boor who tried to favor the South in Reconstruction but was frustrated by Congress.

[214] According to historian Howard K. Beale in his journal article about the historiography of Reconstruction, "Men of the postwar decades were more concerned with justifying their own position than they were with painstaking search for truth.

[215] Other early 20th-century historians, such as John Burgess, future president Woodrow Wilson, and William Dunning, concurred with Rhodes, believing Johnson flawed and politically inept but concluding that he had tried to carry out Lincoln's plans for the South in good faith.

In James Schouler's 1913 History of the Reconstruction Period, the author accused Rhodes of being "quite unfair to Johnson", though agreeing that the former president had created many of his own problems through inept political moves.

According to these writers, Johnson was a humane, enlightened, and liberal statesman who waged a courageous battle for the Constitution and democracy against scheming and unscrupulous Radicals, who were motivated by a vindictive hatred of the South, partisanship, and a desire to establish the supremacy of Northern "big business".

[218] According to historian Glenn W. Lafantasie, who believes James Buchanan the worst president, "Johnson is a particular favorite for the bottom of the pile because of his impeachment ... his complete mishandling of Reconstruction policy ... his bristling personality, and his enormous sense of self-importance.

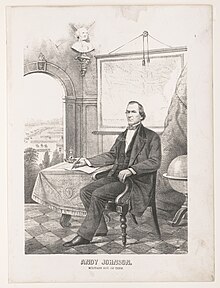

At the same time, Johnson's story has a miraculous quality to it: the poor boy who systematically rose to the heights, fell from grace, and then fought his way back to a position of honor in the country.