1911 Revolution

Several factions, including underground anti-Qing groups, revolutionaries in exile, reformers who wanted to save the monarchy by modernizing it, and activists across the country debated how or whether to overthrow the Qing dynasty.

In December 1915, Yuan restored the monarchy and proclaimed himself as the Hongxian Emperor, but the move was met with strong opposition from the population and the Army, leading to his abdication in March 1916 and the reinstatement of the Republic.

Yuan's failure to consolidate a legitimate central government before his death in June 1916 led to decades of political division and warlordism, including an attempt at imperial restoration of the Qing dynasty.

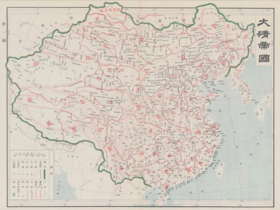

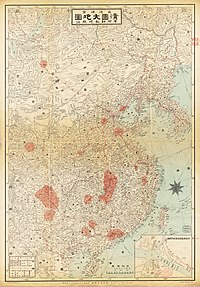

Nationalism (Mínzú) Democracy (Mínquán) Socialism (Mínshēng) After suffering its first defeat by the West in the First Opium War in 1842, a conservative court culture constrained efforts to reform and did not want to cede authority to local officials.

[3] After a generation of relative success in importing Western naval and weapons technology, defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895 was all the more humiliating and convinced many of the need for institutional change.

After the Allies imposed a punitive settlement, the Qing court carried out basic fiscal and administrative reforms, including local and provincial elections.

They could operate only in secret societies and underground organizations, in foreign concessions, or exile overseas, but created a following among Chinese in North America and Southeast Asia, and within China, even in the new armies.

There were 15 members, including Tse Tsan-tai, who did political satire such as "The Situation in the Far East", one of the first manhua, and who later became one of the core founders of the South China Morning Post.

[9] The Huaxinghui (China Revival Society) was founded in 1904 by notables like Huang Xing, Zhang Shizhao, Chen Tianhua, Sun Yat-sen, and Song Jiaoren, along with 100 others.

Zhang Ji and Wang Jingwei were among the anarchists who defended assassination and terrorism as means to awaken the people to revolution, but others insisted that education was the only justifiable strategy.

In 1904, Sun Yat-sen announced that his organization's goal was "to expel the Tatar barbarians, to revive Zhonghua, to establish a Republic, and to distribute land equally among the people."

[24] Many groups supported the 1911 Revolution, including students and intellectuals returning from abroad, as well as participants of revolutionary organizations, overseas Chinese, soldiers of the new army, local gentry, farmers, and others.

Besides Sun Yat-sen, key figures in the revolution, such as Huang Xing, Song Jiaoren, Hu Hanmin, Liao Zhongkai, Zhu Zhixin and Wang Jingwei, were all Chinese students in Japan.

However, after Japanese prime minister Hirobumi Ito prohibited Sun Yat-sen from carrying out revolutionary activities on Taiwan, Zheng Shiliang had no choice but to order the army to disperse.

[46] This involved Tse Tsan-tai, Li Jitang (李紀堂), Liang Muguang (梁慕光) and Hong Quanfu (洪全福), who formerly took part in the Jintian uprising during the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom era.

[48] Wu Yue (吳樾) of the Guangfuhui carried out an assassination attempt at the Beijing Zhengyangmen East Railway station (正陽門車站) in an attack on five Qing officials on 24 September 1905.

[50] The revolutionary party, along with Xu Xueqiu (許雪秋), Chen Yongpo (陳湧波) and Yu Tongshi (余通實), launched the uprising and captured Huanggang city.

[52] On 2 June, Deng Zhiyu (鄧子瑜) and Chen Chuan (陳純) gathered some followers, and together they seized Qing arms in the lake, 20 km (12 mi) from Huizhou.

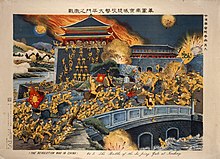

[64] The Literary Society (文學社) and the Progressive Association (共進會) were revolutionary organizations involved in the uprising that mainly began with a Railway Protection Movement protest.

[117] On 23 October, Lin Sen, Jiang Qun (蔣群), Cai Hui (蔡蕙) and other members of the Tongmenghui in the province of Jiangxi plotted a revolt of New Army units.

[72] On 30 October, Li Genyuan (李根源) of the Tongmenghui in Yunnan joined with Cai E, Luo Peijin (羅佩金), Tang Jiyao, and other officers of the New Army to launch the Double Ninth Uprising (重九起義).

They immediately captured Guiyang and established the Great Han Guizhou Military Government, electing Yang Jincheng (楊藎誠) and Zhao Dequan (趙德全) as the chief and vice governor respectively.

[72][137] On 8 November, after being persuaded by Hu Hanmin, General Li Zhun (李準) and Long Jiguang (龍濟光) of the Guangdong Navy agreed to support the revolution.

[150][148] The revolutionaries would be defeated at Jinghe in January and February,[149][151] eventually, because of the abdication to come, Yuan Shikai recognized Yang Zengxin's rule, appointed him Governor of Xinjiang and had the province join the Republic.

[173][174] Despite the general target of the uprisings to be the Manchus, Sun Yat-sen, Song Jiaoren and Huang Xing unanimously advocated racial integration to be carried out from the mainland to the frontiers.

[189][better source needed] The Han hereditary aristocratic nobility like the Duke of Yansheng were retained by the new Republic of China and the title holders continued to receive their pensions.

[191] Anti-Manchu sentiment is recorded in books like A Short History of Slaves (奴才小史) and The Biographies of Avaricious Officials and Corrupt Personnel (貪官污吏傳) by Laoli (老吏).

[192][193][better source needed] During the abdication of the last emperor, Empress Dowager Longyu, Yuan Shikai and Sun Yat-sen both tried to adopt the concept of "Manchu and Han as one family" (滿漢一家.

The writer Lu Xun commented in 1921 during the publishing of The True Story of Ah Q, ten years after the 1911 Revolution, that basically nothing changed except "the Manchus have left the kitchen".

The PRC views Sun's work as the first step toward the real revolution in 1949, when the communists set up a truly independent state that expelled foreigners and built a military and industrial power.