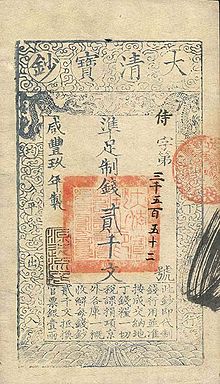

Paper money of the Qing dynasty

The strong influence of these foreign banks had a modernising effect on both the economy and the currency of the Qing dynasty, leading to the imperial government issuing their own versions of modern paper money.

In the early 20th century the government of the Qing dynasty attempted to decimalise the currency among many other economic reforms and established a central bank to oversee the production of paper money; however, the chaotic monetary situation continued to plague interregional trade and would later be inherited by the Republic of China.

Peng Xinwei suggests that the Manchus started issuing banknotes in response to the treasury of the Qing dynasty experiencing funding shortfalls which were occasioned by the a campaign to occupy the island of Zhoushan (near modern Shanghai).

[16] Peng Xinwei suggested that the Manchu rulers of the Qing were very much atavistic towards the inflationary pressure that the earlier Jurchen Empire experienced after they had abused their ability to print Jiaochao banknotes.

It has been suggested by Taiwanese economic historian Lin Man-houng that Chinese money shops did not start the production of their own private banknotes until the end of the Qianlong period.

The fall of the Tian shops was quickened by Chinese peasants who, with the inflation affecting the paper money running rampant, opted to speedily redeem their pawned items with the depreciated Great Qing Treasure Note.

[30] The Tian, Qian, and Yu banks offered money exchange services, accepted deposits, and issued their own banknotes denominated in "metropolitan cash" (Jingqian), hence they were known as Jingpiao (京票) or Jingqianpiao (京錢票).

[32][30] With the Tian, Qian, and Yu banks acting as intermediaries, the government issued paper notes of Ministry of Revenue became convertible:[30] they were linked to both the Daqian and a larger amount in unbacked official banknotes.

[43][44] The qianzhuang would mobilise their domestic resources to an order of magnitude that would exceed the paid-up capital that they initially received several times over; this happened mostly through issuing banknotes and deposit receipts.

During this era foreign banking companies tended to have an account with at least one qianzhuang, since only the guilds operated by them could clear the large number of zhuangpiao forms that were circulating in the city of Shanghai.

Furthermore, there were also banknotes which were brought into the Chinese financial markets by imperial government-owned firms like railway companies, and foreign bills coming to China through the trade ports like Shanghai.

[28] These foreign bank corporations enjoyed the protection of extraterritoriality laws and were able to issue their own banknotes to circulate within Qing territory, had the ability to take in large deposits, and were trusted to manage the Maritime Customs revenue and Chinese government transfers.

The introduction of a uniform currency also meant that the responsibility over monetary affairs would be completely transferred over to the hands of the imperial government which at the time was heavily in debt and did not have any grip on its own finances.

The reformer Liang Qichao campaigned for the government of the Qing dynasty to emulate the Western world and Japan by embracing the gold standard, unifying the currencies of China, and issuing government-backed banknotes with a ⅓ metallic reserve.

The Chartered Mercantile Bank of India, London and China later opened a branch in the British concession of the port city of Shanghai in October 1854, where they issued both silver dollar and tael banknotes.

Because tea could be exported during the summer months, and as opium imports became increasingly restricted by the government of the Qing dynasty, many of these early Anglo-Indian banks in China went bankrupt or had to be reorganised.

[28] The Asiatic Banking Corporation had become dependent on its trade with the Confederate States of America (CSA) and eventually tied its fate to the success of this nation which lost its war of independence in 1865.

The quantity of paper money channeled into Chinese monetary traffic by these Anglo-Indian banks was comparatively small and in some cases exceedingly minor which explains their current rarity.

Sizable portions of some of its early business involved the discounting of bills for the export of the narcotic opium from British India to the Qing dynasty which generated a significant amount of profit.

[28] This negative perception of foreign paper money was in part because of the refusal of the imperial Chinese Customs House stationed there to accept them as valid currency in payment of dues.

With the sole exception of Shanghai, the fiat money issued by the Chartered Bank of India, Australia and China, which may have been circulating in small quantities, was highly regarded by the Chinese public.

[28] The Traditional Chinese characters for the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation were 匯豐銀行 (pinyin: Huìfēng Yínháng; Jyutping: Wui6fung1 Ngan4hong4, which the British pronounced as Wayfung after the Cantonese pronunciation).

As the shareholders of the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation had only very limited liability for the banknotes emissed by the company, HSBC was required to hold ⅓ specie reserve in their vaults at any given time.

[59] The banknotes produced by the Banque de l'Indochine were tri-lingual, printed in French, English, and Mandarin Chinese, making them the only foreign bank to employ three languages on their paper money in China.

[65][59] During the early years of the Yokohama Specie Bank, it survived an economic recession, after which it received loans from the imperial Japanese government and permission to issue its own paper notes.

[59] The 1903 silver yen notes produced by the Niuzhuang branch played an important role in financing local soy bean production in the region of Manchuria.

[67] Approximately a year after it was established the Russo-Chinese Bank received a contract from the government of the Qing dynasty for the construction of the Chinese Eastern Railway in the three provinces making up Manchuria.

[28][69] Banknotes produced by the East Turkestan branches of the Russo-Asiatic Bank (Kashgar, Yining, and Changuchak) during the Republican period circulating between 1913 and 1924 still prominently depicted imperial Chinese symbols such as the five-fingered dragon on both sides.

The main priority for the Deutsch-Asiatische Bank was to finance imperials loans requested by the Qing government with a special focus on both railways and mining operations within the sphere of interest held by the German Empire in the province of Shandong.

[59] While the Netherlands Trading Society's presence in China was small or served as a training base for the future generation of Chinese bankers, many of these native businessmen later went on to form their own private banking companies during the Qing and Republican eras.