1920 Nebi Musa riots

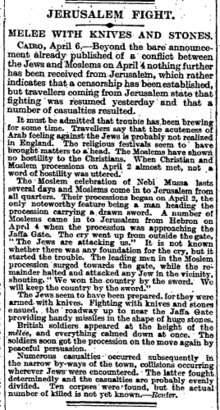

[1] The riots coincided with and are named after the Nebi Musa festival, which was held every year on Easter Sunday, and followed rising tensions in Arab–Jewish relations.

One consequence was that the region's Jewish community increased moves towards an autonomous infrastructure and security apparatus parallel to that of the British administration.

[citation needed] In its wake, sheikhs of 82 villages around the city and Jaffa, claiming to represent 70% of the population, issued a document protesting the demonstrations against the Jews.

[4] Notwithstanding the riots, the Jewish community held elections for the Assembly of Representatives on 19 April 1920 among Jews everywhere in Palestine except Jerusalem, where they were delayed to 3 May.

The contents and proposals of both the Balfour Declaration of 1917 and Paris Peace Conference, 1919, which later concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, were the subject of intensive discussion by both Zionist and Arab delegations, and the process of the negotiations was widely reported in both communities.

The principle of self-determination affirmed by the League of Nations was not to be applied to Palestine, given the foreseeable rejection by the people of Zionism, which the British sponsored.

[6] On 1 March 1920, the death of Joseph Trumpeldor in the Battle of Tel Hai at the hands of a Shiite group from Southern Lebanon caused deep concern among Jewish leaders, who made numerous requests to the OETA administration to address the Yishuv's security and forbid a pro-Syrian public rally.

[1] The Ottoman Turks usually deployed thousands of soldiers and even artillery to keep order in the narrow streets of Jerusalem during the Nebi Musa procession.

[13] The editor of the newspaper Suriya al-Janubia (Southern Syria), Aref al-Aref, another Arab Club member, delivered a speech on horseback at the Jaffa Gate.

According to Benny Morris, he said "If we don't use force against the Zionists and against the Jews, we will never be rid of them",[9] while Bernard Wasserstein wrote "he seems to have co-operated with the police, and there is no evidence that he actively instigated violence".

[1] In Hebrew the incidents were described as meoraot, connoting targeted attacks reminiscent of what had often occurred especially in Russia, whereas Palestinian Arabs referred to them as an heroic witness to an 'Arab Revolt'.

[17] The use of the word pogrom to describe such outbreaks of communal violence bore with it the implication that the governing authorities, in this case the British administration, had actively connived in an anti-Jewish riot.

The term drew an analogy between the classic form such actions took in Eastern Europe, where Jews were the victims of racist, anti-Semitic terror campaigns supported by the ruling authorities, with the situation in Palestine where Zionism was promoting a colonial adventure that was ethnically exclusive and challenged local Arab nationalist aspirations.

[22] The Zionist Commission noted that before the riots Arab milkmen started to demand their customers in Meah Shearim pay them on the spot, explaining that they would no longer be serving the Jewish neighbourhood.

A previous commission report also accused Storrs of inciting the Arabs, blaming him for sabotaging attempts to purchase the Western Wall as well.

[1] After the violence broke out, Ze'ev Jabotinsky met Military Governor Storrs and suggested deployment of his volunteers, but his request was rejected.

[1] On Monday evening, after martial law was declared, the soldiers were evacuated from the Old City, a step described in the Palin Report as "an error of judgment".

"[1] The Palin Report noted that Jewish representatives persisted in describing the events as a "pogrom", implying that the British administration had connived in the violence.

The report blamed the Zionists, 'whose impatience to achieve their ultimate goal and indiscretion are largely responsible for this unhappy state of feeling’[25] and singled out Amin al-Husayni and Ze'ev Jabotinsky in particular.

[26] The report was critical of some of the actions of OETA military command, particularly the withdrawal of troops from inside Jerusalem early on the morning of Monday, 5 April and that, once martial law had been proclaimed, it was slow to regain control.

[14] The Arab riots were publicly protested by sheikhs from 82 villages in the Jerusalem and Jaffa areas who issued a formal statement saying that, in their view, Zionist settlement was not a danger to their communities.

Jabotinsky's trial and sentencing created an uproar, and were protested by London press including The Times and questioned in the British Parliament.

Even before the editorials appeared, the commander of British forces in Palestine and Egypt, General Congreve, wrote Field Marshal Wilson that Jews were sentenced far more severely than Arabs who had committed worse offences.

When the Supreme Muslim Council was created in the following year, Husayni demanded and received the title Grand Mufti,[29][30][31][32] a position which came with life tenure.

Also, feeling that the British were unwilling to defend Jewish settlements from continuous Arab attacks, Palestinian Jews set up self-defense units, which came to be called the Haganah ("defense").