1921 British Mount Everest reconnaissance expedition

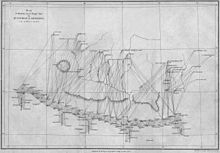

Initially the expedition explored from the north and discovered the main Rongbuk Glacier, only to find that it seemed to provide no likely routes to the summit.

[note 1][1] Mountaineering was in its infancy but antagonism and apathy towards it were waning so, by 1907, to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the Alpine Club, a definite plan was hatched for a British reconnaissance of Everest.

[2][3] Initially, the British Secretary of State for India, Lord Morley, refused permission for an expedition out of "consideration of high Imperial policy".

[2][5] By 1920 the Secretary of State had given approval for an expedition so Colonel Charles Howard-Bury was sent on a diplomatic mission which persuaded the Viceroy of India, Lord Reading, to support that idea.

[7] The viceroy's agent there, Sir Charles Bell, had been working in Lhasa and he had formed a good relationship with the Dalai Lama, who granted an entry pass for the expedition.

[8][note 2] In January 1921 the Alpine Club and the Royal Geographical Society (of which Younghusband was now President) jointly set up the Mount Everest Committee to co-ordinate and fund the expedition.

[4][9][5] Although they initially supported an all-out attempt at the summit, members of the committee eventually agreed that the primary purpose of the mission should be reconnaissance.

[11] The expedition set off in April 1921 – the climbing team consisted of two experienced mountaineers, Harold Raeburn and Alexander Kellas, and two younger men, George Mallory and Guy Bullock, both Old Wykehamists without any Himalayan experience.

[12][13] The expedition team also included Sandy Wollaston, a naturalist and doctor, Alexander Heron, a geologist, Henry Morshead (also an Old Wykehamist) and Oliver Wheeler, surveyors seconded from the army.

[4][14][15] When George Bernard Shaw saw a photograph (above) of them wearing Norfolk jackets, knickerbockers, puttees and tweeds he quipped that they "looked like a Connemara picnic trapped in a snowstorm".

[14][4] During their march, the climate changed from hot and humid with verdant growth and heavy, frequent rain, to cold, dry and very windy.

[29] The topography to the west is very complex so on 5 July Mallory and Bullock climbed the 6,900-metre (22,500 ft) Ri Ring[note 6] to get a better perspective.

However, they formed a wrong impression that a high ridge ran from Everest's North Peak[note 7] stretching away east to the Arun river.

[note 10] So they crossed a 5,500 metres (18,000 ft) pass to reach the valley of the Kama River which runs parallel but to the south.

Surrounded by three of the highest peaks in the world Mallory wrote of the Kama valley, "For me the most magnificent and sublime mountain scenery can be made lovelier by some more tender touch; and that too is added here".

"[56][note 11] They realised that they would have to return to the Kharta valley and to achieve this they climbed the 6,520-metre (21,390 ft) Khartse [de] on 7 August so they could examine the North Col as well as the Kangshung Face.

They had to wait for a month for the monsoon to end and on 31 August all the team tentatively moved to advance base camp with Raeburn, who had unexpectedly returned, able to join them.

[66] They had to stay at advance base camp until 20 September for the weather to improve and then Mallory, Bullock, Morshead and Wheeler set off for and reached Lhakpa La.

After a very difficult night on the glacier in cold and windy conditions, the following day, 24 September, saw the party reach the North Col although without carrying loads.

They descended to the glacier where Mallory and Bullock calculated that they would not be able to set up a camp on the North Col, nor could they survive a bivouac up there at 7,000 metres (23,000 ft).

[71] Before the expedition had left Tibet, the Mount Everest Committee met and decided that a full assault should be made on the mountain in 1922 with General Bruce as leader.

[72] The 1921 expedition was regarded as successful by experts as well as the general public with large numbers of people turning up for the official welcome home by the Royal Geographical Society and the Alpine Club at the Queen's Hall in London.

[73][74] Speaking of the future summit attempt in his Queen's Hall address Mallory said he was "very far from a sanguine estimate of success ... A party or two arriving the top, each so tired that it was beyond helping the other, might provide good copy for the Press but the performance would provoke the censure of reasonable opinion".

Standing: Wollaston, Howard-Bury, Heron, Raeburn.

Sitting: Mallory, Wheeler, Bullock, Morshead.