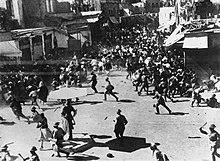

1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine

[12] The uprising occurred during a peak in the influx of European Jewish immigrants,[13] and with the growing plight of the rural fellahin rendered landless, who as they moved to metropolitan centres to escape their abject poverty found themselves socially marginalized.

[20] By October 1936, this phase had been defeated by the British civil administration using a combination of political concessions, international diplomacy (involving the rulers of Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Transjordan and Yemen)[21] and the threat of martial law.

[31] The Ottoman and then the Mandate authorities levied high taxes on farming and agricultural produce and during the 1920s and 1930s this together with a fall in prices, cheap imports, natural disasters and paltry harvests all contributed to the increasing indebtedness of the fellahin.

[13] The Shaw Commission in 1930 had identified the existence of a class of 'embittered landless people' as a contributory factor to the preceding 1929 disturbances,[35] and the problem of these 'landless' Arabs grew particularly grave after 1931, causing High Commissioner Wauchope to warn that this 'social peril ... would serve as a focus of discontent and might even result in serious disorders.

[14] Palestine's fellahin, the country's peasant farmers, made up over two-thirds of the indigenous Arab population and from the 1920s onwards they were pushed off the land in increasingly large numbers into urban environments where they often encountered only poverty and social marginalisation.

[38] The ongoing disruption of agrarian life in Palestine, which had been continuing since Ottoman times, thus created a large population of landless peasant farmers who subsequently became mobile wage workers who were increasingly marginalised and impoverished; these became willing participants in nationalist rebellion.

[54] In Iraq a general strike in July 1931, accompanied by organised demonstrations in the streets, led to independence for the former British mandate territory under Prime Minister Nuri as-Said, and full membership of the League of Nations in October 1932.

[57] On 16 October 1935 a large arms shipment camouflaged in cement bins, comprising 25 Lewis guns and their bipods, 800 rifles and 400,000 rounds of ammunition[58] destined for the Haganah, was discovered during unloading at the port of Jaffa.

[84] The pro-Government Mayor of Nablus complained to the High Commissioner that, "During the last searches effected in villages properties were destroyed, jewels stolen, and the Holy Qur'an torn, and this has increased the excitement of the fellahin.

[85] On 2 June, an attempt by rebels to derail a train bringing the 2nd Battalion Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire Regiment from Egypt led to the railways being put under guard, placing a great strain on the security forces.

[88] A Statement of Policy issued by the Colonial Office in London on 7 September declared the situation a "direct challenge to the authority of the British Government in Palestine" and announced the appointment of Lieutenant-General John Dill as supreme military commander.

[103] With the failure of the Peel Commission's proposals the revolt resumed during the autumn of 1937 marked by the assassination on 26 September of Acting District Commissioner of the Galilee Lewis Andrews by Quassemite gunmen in Nazareth.

[105] On 30 September, regulations were issued allowing the Government to detain political deportees in any part of the British Empire, and authorising the High Commissioner to outlaw associations whose objectives he regarded as contrary to public policy.

[1] These collective fines (amounting to £1,000,000 over the revolt[112]) eventually became a heavy burden for poor Palestinian villagers, especially when the army also confiscated livestock, destroyed properties, imposed long curfews and established police posts, demolished houses and detained some or all of the Arab men in distant detention camps.

[1] Despite these measures Lieutenant-General Haining, the General Officer Commanding, reported secretly to the Cabinet on 1 December 1938 that "practically every village in the country harbours and supports the rebels and will assist in concealing their identity from the Government Forces.

[116] It was common British army practice to use local Arabs as human shields by forcing them to ride with military convoys to prevent mine attacks and sniping incidents: soldiers would tie the hostages to the bonnets of lorries, or put them on small flatbeds on the front of trains.

On the lorries, some soldiers would brake hard at the end of a journey and then casually drive over the hostage, killing or maiming him, as Arthur Lane, a Manchester Regiment private recalled: ... when you'd finished your duty you would come away nothing had happened no bombs or anything and the driver would switch his wheel back and to make the truck waver and the poor wog on the front would roll off into the deck.

[119] Like many of those enrolled in the Palestinian gendarmerie, Tegart had served in Great Britain's repression of the Irish War of Independence, and the security proposals he introduced exceeded measures adopted down to this time elsewhere in the British Empire.

[135] Following the Irgun's detonation of a large bomb in a market in Haifa on 6 July 1938 the High Commissioner signalled the Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet, Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, requesting the assistance of naval vessels capable of providing landing parties.

[150] Shertok also advised the administration on political affairs, on one occasion convincing the high commissioner not to arrest Professor Joseph Klausner, a Revisionist Maximalist activist who had played a key role in the riots of 1929, because of the likely negative consequences.

[155] The agreement brought 52,000 German Jews to Palestine between 1933 and 1939, and generated $30,000,000 for the then almost bankrupt Jewish Agency, but in addition to the difficulties with the Revisionists, who advocated a boycott of Germany, it caused the Yishuv to be isolated from the rest of world Jewry.

[j] In October 1937, shortly after Mohammad Amin al-Husayni, the leader of the Arab Higher Committee, had fled from Palestine to escape British retribution, Raghib al-Nashashibi had written to Moshe Shertok stating his full willingness to co-operate with the Jewish Agency and to agree with whatever policy it proposed.

[166] Fakhri Nashashibi was particularly successful in recruiting peace bands in the Hebron hills, on one occasion in December 1938 gathering 3,000 villagers for a rally in Yatta, also attended by the British military commander of the Jerusalem District General Richard O'Connor.

[171] Abdul Khallik was an effective peasant leader appointed by Fawzi al-Qawuqji who caused great damage and loss of life in the Nazareth District and was thus a significant adversary of the Mandate and Jewish settlement authorities.

[citation needed] In the contest of wills between the British Empire and Palestinian aspirants for statehood, the respective efforts to secure the financial means to sustain the hostilities also played out as a battle for funding.

Women donated jewelry and ran fund-raising committees, a jihad tax was placed on citrus groves, the industry being the backbone of Palestine's export trade; Palestinians on the government payroll contributed sums anywhere up to half of their salaries; levies were imposed on wealthier Arabs (many of whom went abroad to avoid paying them, or because they could not meet demands to provide financial aid to strikers).

[195] By 1938 the drop in revenues caused militant gangs to resort to extortion and robbery, often draining villages of ready cash reserves set aside to pay government fines, which then had to be met by the sale of crops and livestock.

[195] A great deal of speculation later arose around the purported role of Germany and Italy in backing the revolt financially, based on early claims by Jewish operatives that both countries were fomenting the uprising by funneling cash and weapons to the insurgents.

[217] In the event the White Paper quotas were exhausted only in December 1944, over five and a half years later, and in the same period the United Kingdom absorbed 50,000 Jewish refugees and the British Commonwealth (Australia, Canada and South Africa) took many thousands more.

"[225] In February 1939 Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs Malcolm MacDonald called together a conference of Arab and Zionist leaders on the future of Palestine at St. James's Palace in London but the discussions ended without agreement on 27 March.