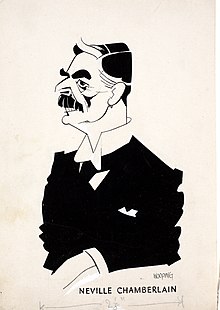

Neville Chamberlain

Defunct Arthur Neville Chamberlain (/ˈtʃeɪmbərlɪn/; 18 March 1869 – 9 November 1940) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940 and Leader of the Conservative Party from May 1937 to October 1940.

Until ill health forced him to resign on 22 September 1940, Chamberlain was an important member of the war cabinet as Lord President of the Council, heading the government in Churchill's absence.

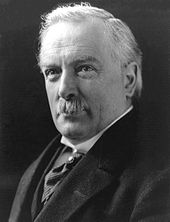

[25] In December 1916, Prime Minister David Lloyd George offered Chamberlain the new position of Director of National Service, with responsibility for co-ordinating conscription and ensuring that essential war industries were able to function with sufficient workforces.

Chamberlain reacted to this intervention by being one of the few male candidates to specifically target women voters deploying his wife, issuing a special leaflet headed "A word to the Ladies" and holding two meetings in the afternoon.

[41] When Sir Arthur Griffith-Boscawen, the Minister of Health, lost his seat in the 1922 election and was defeated in a by-election in March 1923 by future home secretary James Chuter Ede, Law offered the position to Chamberlain.

At 68 he was the second-oldest person in the 20th century (after Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman) to become prime minister for the first time,[73] and was widely seen as a caretaker who would lead the Conservative Party until the next election and then step down in favour of a younger man, with Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden a likely candidate.

The Anglo-Irish Trade War, sparked by the withholding of money that Ireland had agreed to pay the United Kingdom, had caused economic losses on both sides, and the two nations were anxious for a settlement.

[83] The Irish proved very tough negotiators, so much so that Chamberlain complained that one of de Valera's offers had "presented United Kingdom ministers with a three-leafed shamrock, none of the leaves of which had any advantages for the UK.

[83] Churchill railed against these treaties in The Gathering Storm, stating that he "never saw the House of Commons more completely misled" and that "members were made to feel very differently about it when our existence hung in the balance during the Battle of the Atlantic.

After the fall of Austria, the Cabinet's Foreign Policy Committee considered seeking a "grand alliance" to thwart Germany or, alternatively, an assurance to France of assistance if the French went to war.

[113] Convinced that the French would not fight (Daladier was privately proposing a three-Power summit to settle the Sudeten question), Chamberlain decided to implement "Plan Z" and sent a message to Hitler that he was willing to come to Germany to negotiate.

Chamberlain objected strenuously, telling Hitler that he had worked to bring the French and Czechoslovaks into line with Germany's demands, so much so that he had been accused of giving in to dictators and had been booed on his departure that morning.

[123] On the evening of 27 September, Chamberlain addressed the nation by radio, and after thanking those who wrote to him, stated: How horrible, fantastic, incredible it is that we should be digging trenches and trying on gas-masks here because of a quarrel in a far-away country between people of whom we know nothing.

Large crowds mobbed Heston, where he was met by the Lord Chamberlain, the Earl of Clarendon, who gave him a letter from King George VI assuring him of the Empire's lasting gratitude and urging him to come straight to Buckingham Palace to report.

"[137] Nevertheless, in his statement to the crowd, Chamberlain recalled the words of his predecessor, Benjamin Disraeli, upon the latter's return from the Congress of Berlin:[c] My good friends, this is the second time there has come back from Germany to Downing Street peace with honour.

[159] Instead, on 31 March 1939, Chamberlain informed an approving House of Commons of British and French guarantees that they would lend Poland all possible aid in the event of any action which threatened Polish independence.

[164] On 17 June 1939, Handley Page received an order for 200 Hampden twin-engined medium bombers, and by 3 September 1939, the chain of radar stations girding the British coast was fully operational.

[165] Chamberlain was reluctant to seek a military alliance with the Soviet Union; he distrusted Joseph Stalin ideologically and felt that there was little to gain, given the recent massive purges in the Red Army.

When the House of Commons met at 6:00 pm, Chamberlain and Labour deputy leader Arthur Greenwood (deputising for the sick Clement Attlee) entered the chamber to loud cheers.

[175] Chamberlain's last peacetime Cabinet met at 11:30 that night, with a thunderstorm raging outside, and determined that the ultimatum would be presented in Berlin at nine o'clock the following morning—to expire two hours later, before the House of Commons convened at noon.

"[180] Chamberlain also deterred some of Churchill's plans, such as Operation Catherine, which would have sent three heavily armoured battleships into the Baltic Sea with an aircraft carrier and other support vessels as a means of stopping shipments of iron ore to Germany.

[183] Chamberlain, in common with most Allied officials and generals, felt the war could be won relatively quickly by keeping economic pressure on Germany through a blockade while continuing rearmament.

The initial speeches, including Chamberlain's, were nondescript, but Admiral of the Fleet Sir Roger Keyes, member for Portsmouth North, in full uniform, delivered a withering attack on the conduct of the Norway campaign, though he excluded Churchill from criticism.

[208] Halifax reported to the War Cabinet on 26 May 1940, with the Low Countries conquered and French prime minister Paul Reynaud warning that France might have to sign an armistice, that diplomatic contacts with a still-neutral Italy offered the possibility of a negotiated peace.

[211] In July 1940, a polemic titled Guilty Men was released by "Cato"—a pseudonym for three journalists (future Labour leader Michael Foot, former Liberal MP Frank Owen, and the Conservative Peter Howard).

Though a few Conservatives offered their own versions of events, most notably MP Quintin Hogg in his 1945 The Left Was Never Right, by the end of the war, there was a very strong public belief that Chamberlain was culpable for serious diplomatic and military misjudgements that had nearly caused Britain's defeat.

[230] Anne Chamberlain, the former premier's widow, suggested that Churchill's work was filled with matters that "are not real misstatements that could easily be corrected, but wholesale omissions and assumptions that certain things are now recognised as facts which actually have no such position".

The same year, A. J. P. Taylor, in his The Origins of the Second World War, found that Chamberlain had adequately rearmed Britain for defence (though a rearmament designed to defeat Germany would have taken massive additional resources) and described Munich as "a triumph for all that was best and most enlightened in British life ... [and] for those who had courageously denounced the harshness and short-sightedness of Versailles".

[238] Other released papers showed that Chamberlain had considered seeking a grand coalition amongst European governments like that later advocated by Churchill, but had rejected it on the grounds that the division of Europe into two camps would make war more, not less likely.

Oxford historian R. A. C. Parker argued that Chamberlain could have forged a close alliance with France after the Anschluss, in early 1938, and begun a policy of containment of Germany under the auspices of the League of Nations.