Voting Rights Act of 1965

[7][8] It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights movement on August 6, 1965, and Congress later amended the Act five times to expand its protections.

Further protections were enacted in the Civil Rights Act of 1960, which allowed federal courts to appoint referees to conduct voter registration in jurisdictions that engaged in voting discrimination against racial minorities.

[9] Although these acts helped empower courts to remedy violations of federal voting rights, strict legal standards made it difficult for the Department of Justice to successfully pursue litigation.

Moreover, the department often needed to appeal lawsuits several times before the judiciary provided relief because many federal district court judges opposed racial minority suffrage.

[33]: 253 President Lyndon B. Johnson recognized this, and shortly after the 1964 elections in which Democrats gained overwhelming majorities in both chambers of Congress, he privately instructed Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach to draft "the goddamndest, toughest voting rights act that you can".

'"[33]: 255 In January 1965, Martin Luther King Jr., James Bevel,[34][35] and other civil rights leaders organized several peaceful demonstrations in Selma, which were violently attacked by police and white counter-protesters.

[33]: 264 On February 18 in Marion, Alabama, state troopers violently broke up a nighttime voting-rights march during which officer James Bonard Fowler shot and killed young African-American protester Jimmie Lee Jackson, who was unarmed and protecting his mother.

[7] The United States Supreme Court explained this in South Carolina v. Katzenbach (1966) with the following words: In recent years, Congress has repeatedly tried to cope with the problem by facilitating case-by-case litigation against voting discrimination.

Perfecting amendments in the Civil Rights Act of 1960 permitted the joinder of States as parties defendant, gave the Attorney General access to local voting records, and authorized courts to register voters in areas of systematic discrimination.

Even when favorable decisions have finally been obtained, some of the States affected have merely switched to discriminatory devices not covered by the federal decrees, or have enacted difficult new tests designed to prolong the existing disparity between white and Negro registration.

Congress had found that case-by-case litigation was inadequate to combat widespread and persistent discrimination in voting, because of the inordinate amount of time and energy required to overcome the obstructionist tactics invariably encountered in these lawsuits.

Congress had learned that substantial voting discrimination presently occurs in certain sections of the country, and it knew no way of accurately forecasting whether the evil might spread elsewhere in the future.

[28]: 521 [33]: 285 Additionally, by excluding poll taxes from the definition of "tests or devices", the coverage formula did not reach Texas or Arkansas, mitigating opposition from those two states' influential congressional delegations.

In response, Dirksen offered an amendment that exempted from the coverage formula any state that had at least 60 percent of its eligible residents registered to vote or that had a voter turnout that surpassed the national average in the preceding presidential election.

It would have allowed the attorney general to appoint federal registrars after receiving 25 serious complaints of discrimination against a jurisdiction, and it would have imposed a nationwide ban on literacy tests for persons who could prove they attained a sixth-grade education.

McCulloch's bill was co-sponsored by House minority leader Gerald Ford (R-MI) and supported by Southern Democrats as an alternative to the Voting Rights Act.

To assuage concerns of liberal committee members that this provision was not strong enough, Katzenbach enlisted the help of Martin Luther King Jr., who gave his support to the compromise.

[28]: 644–645 In 2006, Congress amended the Act to overturn two Supreme Court cases: Reno v. Bossier Parish School Board (2000),[60] which interpreted the Section 5 preclearance requirement to prohibit only voting changes that were enacted or maintained for a "retrogressive" discriminatory purpose instead of any discriminatory purpose, and Georgia v. Ashcroft (2003),[61] which established a broader test for determining whether a redistricting plan had an impermissible effect under Section 5 than assessing only whether a minority group could elect its preferred candidates.

[84] There is a statutory framework to determine whether a jurisdiction's election law violates the general prohibition from Section 2 in its amended form:[85] Section 2 prohibits voting practices that “result[] in a denial or abridgment of the right * * * to vote on account of race or color [or language-minority status],” and it states that such a result “is established” if a jurisdiction’s “political processes * * * are not equally open” to members of such a group “in that [they] have less opportunity * * * to participate in the political process and to elect representatives of their choice.” 52 U.S.C.

The new language was crafted as a compromise designed to eliminate the need for direct evidence of discriminatory intent, which is often difficult to obtain, but without embracing an unqualified “disparate impact” test that would invalidate many legitimate voting procedures.

[100] The court emphasized that the existence of the three Gingles preconditions may be insufficient to prove liability for vote dilution through submergence if other factors weigh against such a determination, especially in lawsuits challenging redistricting plans.

In particular, the court held that even where the three Gingles preconditions are satisfied, a jurisdiction is unlikely to be liable for vote dilution if its redistricting plan contains a number of majority-minority districts that is proportional to the minority group's population size.

In Holder v. Hall (1994),[116] the Supreme Court held that claims that minority votes are diluted by the small size of a governing body, such as a one-person county commission, may not be brought under Section 2.

[124] Originally, the Act suspended tests or devices temporarily in jurisdictions covered by the Section 4(b) coverage formula, but Congress subsequently expanded the prohibition to the entire country and made it permanent.

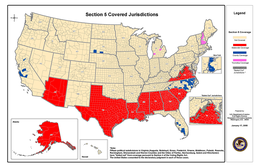

In Shelby County v. Holder (2013), the Supreme Court declared the coverage formula unconstitutional because the criteria used were outdated and thus violated principles of equal state sovereignty and federalism.

The Supreme Court broadly interpreted Section 5's scope in Allen v. State Board of Election (1969),[139] holding that any change in a jurisdiction's voting practices, even if minor, must be submitted for preclearance.

"[21] A 2013 Quarterly Journal of Economics study found that the Act boosted voter turnout and increases in public goods transfers from state governments to localities with higher black population.

On the seventh day of March, in the landmark case of South Carolina v. Katzenbach (1966), the Supreme Court held that the Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a constitutional method to enforce the Fifteenth Amendment.

The Democratic National Committee asserted a set of Arizona election laws and policies were discriminatory towards Hispanics and Native Americans under section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

For race to "predominate", the jurisdiction must prioritize racial considerations over traditional redistricting principles, which include "compactness, contiguity, [and] respect for political subdivisions or communities defined by actual shared interests.