1987 Forsyth County protests

In light of this, in 1987, a local resident announced plans for a march to occur on the weekend of Martin Luther King Jr. Day to draw attention to the county's history and continuing problems with race.

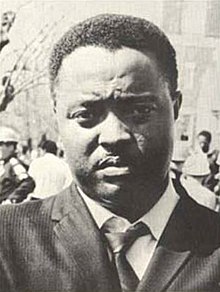

Hosea Williams, a civil rights activist and politician in Atlanta, joined the project and helped lead a group of about 75 marchers through the county on January 17.

About two weeks after the second march, Oprah Winfrey traveled to Cumming to broadcast an episode of her talk show, interviewing several white residents.

Additionally, the Southern Poverty Law Center sued several white supremacist organizations and individuals for damages from the protests and won nearly $1 million in a federal case that resulted in the dissolution of one of the groups involved.

[2][3] For much of the 20th century, the primarily rural county had a long history of poor race relations and a reputation as a hostile place for African Americans.

[4] In the aftermath of this event, some white people known as "night riders" waged a months-long terror campaign of whitecapping that resulted in the expulsion of almost all African Americans from the county.

[9][12][13] Also during this time, as Lake Lanier (which constituted the eastern border of the county) developed into a popular recreational destination, African American vacationers faced discrimination and threats from locals.

[18][2][19] That year, Charles A. Blackburn, a white resident of Cumming, announced plans for a civil rights march to draw attention to the county's racial problems.

[21] Dean and Tammy Carter, two residents of Gainesville, Georgia,[11] revived the idea and invited Hosea Williams,[12] a civil rights activist and member of the Atlanta City Council, proposing a "March against Fear and Intimidation" in the county on January 17.

[16] It was scheduled to take place the weekend before Martin Luther King Jr. Day, which had been established as a federal holiday only four years earlier, in 1983, and had quickly become, according to human rights activist and academic Leonard Zeskind, "a flashpoint for white supremacists".

[15] In the weeks leading up to the march, Ku Klux Klan (KKK) groups and white supremacists in north Georgia began to coordinate plans to disrupt the event, which they said was being organized by "outside agitators and communist racemixers".

[12] Regarding the racial climate at the time, activist and pastor Cecil Williams of the Glide Memorial United Methodist Church in San Francisco said, "Just when we thought we had swept the whirlwind of racism into the corners of society, now we see it is blowing back into the center of the floor".

[19] The march was planned to begin at Bethel View Road near an offramp of Georgia State Route 400 and go for several miles through the county until ending in Cumming.

B. Stoner, Daniel Carver,[32] and Dave Holland, who was the grand dragon of a KKK organization, were present and gave speeches that energized the group of counterdemonstrators.

[32] The violence ultimately prompted the march organizers to call off the event prematurely after law enforcement officials told them that they could not guarantee their safety.

[22] Speaking of the event later, Williams stated, "In thirty years in the civil rights movement, I haven't seen racism any more sick than here today".

[28] Talking to The New York Times, Williams compared the county to South Africa under apartheid and said that children as young as ten or 12 had yelled death threats and racial slurs at the marchers.

[19][9] The march and accompanying violence attracted national attention,[24][34] and local leaders attempted to mitigate some of the bad publicity, with the chamber of commerce putting full-page advertisements on newspapers stating that the racists' actions did not represent the people of Forsyth County.

[2] Other noted civil rights activists included Southern Christian Leadership Conference president Joseph Lowery,[2] NAACP executive director Benjamin Hooks, A. James Rudin of the American Jewish Committee,[26] Ralph Abernathy, Dick Gregory, Jesse Jackson, and Coretta Scott King, the widow of Martin Luther King Jr.[41] As with last time, there was a large number of white supremacists who had gathered in Forsyth County, numbering over 1,000.

[41][note 9] Many of these individuals, which included neo-Nazis from organizations in the surrounding states,[37] participated in a countermarch led by white nationalist lawyer Richard Barrett of Mississippi.

[2] Duke had come to the march at the invitation of Atlanta racial extremist Ed Fields and a local group called the Committee to Keep Forsyth White, and he was joined by fellow former Klansman Don Black and Maddox.

[2] This was also in line with a pledge made by Forsyth County Sheriff Wesley Walraven, who had told Williams after the first march was called off that he would guarantee the protestors safety if they returned next weekend.

[41][2][28][note 12] One man was hit by a cement block and a woman was struck by a steel pipe,[43] but, according to a report by the Los Angeles Times, "the march was not marred by major clashes or injuries".

[51][52] Following the white supremacist Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017 that resulted in the death of a counter-protester in a terrorist attack, several publications made comparisons between the violence there and that witnessed in Forsyth County in 1987.

[16] Additionally, on February 9,[17] they announced the creation of a biracial human relations committee to help address racial issues in the county.

[60] As a result of the ruling, James Farrands, the leader of the Invisible Empire, agreed to relinquish all of the organization's assets, including its name, and personally paid $37,500 to the affected marchers.

[41][62] This came up in January 1989, when the Nationalist Movement made plans to hold a demonstration on the steps of the Forsyth County Courthouse in opposition of Martin Luther King Jr.

[1] The case made its way before the Supreme Court of the United States, with the American Civil Liberties Union writing an amicus brief in favor of the Nationalist Movement.

[41] In the end, the Supreme Court decided in favor of the Nationalist Movement, ruling that the county's permit fees system was unconstitutional.