1995 Quebec referendum

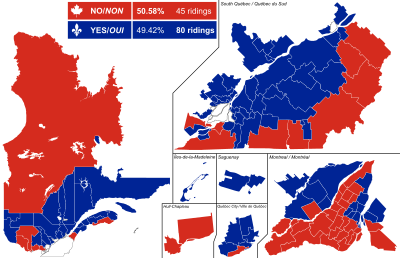

The culmination of multiple years of debate and planning after the failure of the Meech Lake and Charlottetown constitutional accords, the referendum was launched by the provincial Parti Québécois government of Jacques Parizeau.

[1] Parizeau, who announced his pending resignation as Quebec premier the following day, later stated that he would have quickly proceeded with a unilateral declaration of independence had the result been affirmative and negotiations failed or been refused,[2] the latter of which was later revealed as the federal position in the event of a "Yes" victory.

Controversies over both the provincial vote counting and direct federal financial involvement in the final days of the campaign reverberated in Canadian politics for over a decade after the referendum took place.

The Accord, after fierce debate in English Canada, fell apart in dramatic fashion in the summer of 1990, as two provinces failed to ratify it within the three-year time limit required by the constitution.

In the 1993 federal election, the Liberals returned to power with a majority government under Jean Chrétien, who had been Minister of Justice during the 1980–81 constitutional discussions and the Bloc Québécois won 54 seats with 49.3% of Quebec's vote.

The result made the Bloc the second largest party in the House of Commons, giving it the role of Official Opposition and allowing Bouchard to confront Chrétien in Question Period on a daily basis.

Parizeau, long identified with the independantiste wing of the party, was opposed to the PQ's general historical preference for an economic relationship with the rest of Canada to be offered alongside sovereignty, as he thought this would encourage the Federal government to simply refuse to negotiate and cast the project as doomed, as had happened in 1980.

After Parizeau moved the planned referendum date to the fall, Deputy Premier Bernard Landry aroused ire by stating he would not want to be involved in a "charge of the light brigade."

During the Bloc's April conference, after a speech demanding a change in direction, Bouchard expressed ambivalence to a radio show about participating if a partnership proposal was not included.

Chrétien's involvement in the 1982 negotiations and his stance against the Meech Lake Accord made him unpopular with moderate francophone federalists and sovereignists, who would be the swing voters in the referendum.

[26] Jean Charest, leader of the Federal Progressive Conservative Party, would be prominently featured, as he and the PCs had closely and productively cooperated with the Quebec Liberals in the Meech Lake negotiations.

[33] Johnson's campaign focused on the practical problems created by the sovereignty process, emphasizing that an independent Quebec would be in an uncertain position regarding the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and not be able to control the Canadian dollar.

In addition to the traditional themes of the movement's appeal to Quebec nationalism, the "Yes" campaign attempted to highlight the slim possibility of any future reform to Canada's federal system.

[39] In an unannounced ceremony on October 7 at the Université de Montréal, Parizeau made a surprise announcement: He appointed Bouchard as "chief negotiator" for the partnership talks following a "Yes" vote.

[41] Bouchard, already popular, became a sensation: in addition to his medical struggles and charisma, his more moderate approach and prominent involvement in the Meech Lake Accord while in Ottawa reminded undecided nationalist voters of federal missteps from years past.

[49] Bouchard's popularity was such that his remarks that the Québécois were the "white race" with the lowest rate of reproduction, which threatened to cast the project as focused on ethnic nationalism, were traversed with ease.

[58] French President Jacques Chirac, while answering a call from a viewer in Montreal on CNN's Larry King Live, said that, if the "Yes" side were successful, the fact that the referendum had succeeded would be recognized by France.

Grand Chief Matthew Coon Come issued a legal paper, titled Sovereign Injustice,[63] which sought to affirm the Cree right to self-determination in keeping their territories in Canada.

[69] Fisheries Minister Brian Tobin, expressing anxiety to his staff about the referendum the week before, was told about a small rally planned in Place du Canada in Montreal for businesspersons on October 27.

[86] "No" supporters gathered at Métropolis in Montreal, where Johnson expressed hope for reconciliation in Quebec and stated he expected the federal government to pursue constitutional changes.

[90] The remarks, widely lambasted in the Canadian and international press as ethnocentric, sparked surprise and anger in the "Yes" camp, as the movement had gone to great lengths to disown ethnic nationalism.

[98] Parizeau's immediate plans after the referendum relied upon what he felt would be general pressure from economic markets and the business community in English Canada to stabilize the situation as quickly as possible, which he believed would mitigate any catastrophic initial events (such as blockades) and prepare for negotiations.

[104] Benoit Bouchard, Canada's ambassador at the time, believed that the plan was irrational as he doubted Séguin, who was supposed to be a neutral figure in his role, could bring sufficient pressure in the country's semi-presidential system.

[112][113] Jean Chrétien refused to publicly comment or consider contingencies regarding a possible "Yes" victory, and at no point stated the referendum bound the Federal government to negotiations or permitted a unilateral declaration of independence.

[114] Reform party leader Preston Manning, a prominent proponent of direct democracy, would have recognized any result, with critics suspecting he preferred a "Yes" vote for electoral gain.

[115] Jean Charest recognized the referendum's legitimacy, although a draft post-referendum speech had him interpreting a "Yes" vote as a call for drastic reform of Canadian federation instead of separation.

[117] Manning intended to immediately call for Chrétien's resignation and for a general election if the referendum were successful,[118] even though the Liberals, independently of their Quebec seats, had a sizable majority in the House of Commons.

[128] Directeur général des élections du Québec (DGEQ), Pierre F. Cote, launched an inquiry into the alleged irregularities, supervised by the Chief Justice of the Quebec Superior Court, Alan B.

Aurèle Gervais, communications director for the Liberal Party of Canada, as well as the students' association at Ottawa's Algonquin College, were charged with infractions of Quebec's Election Act after the referendum for illegally hiring buses to bring supporters to Montreal for the rally.

Bouchard retired in 2001 and was replaced by Bernard Landry who, despite promising a more robust stance on the sovereignty issue,[153] was ousted in the 2003 Quebec general election by Charest, who would become premier.