1996 Mount Everest disaster

Anatoli Boukreev, a guide in the Mountain Madness team, felt impugned by the book and co-authored a rebuttal called The Climb: Tragic Ambitions on Everest (1997).

[6] In 2014, Lou Kasischke, also of Hall's expedition, published his own account in After the Wind: 1996 Everest Tragedy, One Survivor's Story.

Graham Ratcliffe, who climbed to the South Col of Everest on 10 May, noted in A Day to Die For (2011) that weather reports forecasting a major storm developing after 8 May and peaking in intensity on 11 May were delivered to expedition leaders.

The following is a list of climbers en route to the summit on 10 May 1996 via the South Col and Southeast Ridge, organized by expedition and role.

Legendary Sardar Apa Sherpa was scheduled to accompany the Adventure Consultants group but withdrew due to family commitments.

[8] With the exception of Namba, none of the clients on Hall's team had ever reached the summit of an 8,000-meter peak, and only Fischbeck, Hansen, and Hutchison had previous high-altitude Himalayan experience.

Hall had also brokered a deal with Outside magazine for advertising space in exchange for a story about the growing popularity of commercial expeditions to Everest.

[7] Ngawang Topche was hospitalized in April; he had developed high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) while ferrying supplies above Base Camp.

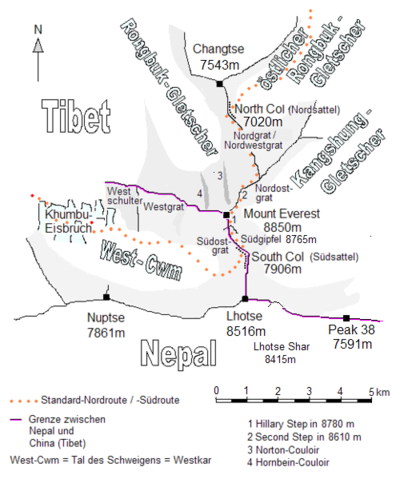

Shortly after midnight on 10 May 1996, the Adventure Consultants expedition began a summit attempt from Camp IV, atop the South Col (7,900 m or 25,900 ft).

They were joined by six client climbers, three guides, and Sherpas from Scott Fischer's Mountain Madness company, as well as an expedition sponsored by the government of Taiwan.

The climbing Sherpas and guides had not set the fixed ropes by the time the team reached the Balcony (8,350 m or 27,400 ft), and this cost the climbers almost an hour.

[15] Upon reaching the Hillary Step (8,760 m or 28,740 ft), the climbers again discovered that no fixed line had been placed, and they were forced to wait an hour while the guides installed the ropes.

[19] Boukreev maintained that he wanted to be ready to assist struggling clients farther down the slope, and to retrieve hot tea and extra oxygen if necessary.

[21] Boukreev's supporters, who include G. Weston DeWalt, co-author of The Climb (1997), state that using bottled oxygen gives a false sense of security.

The blizzard on the southwest face of Everest was reducing visibility, burying the fixed ropes, and obliterating the trail back to Camp IV that the teams had broken on the ascent.

At 17:30, Adventure Consultants guide Andy Harris, carrying supplementary oxygen and water, began climbing alone from the South Summit (8,749 m or 28,704 ft) toward Hansen and Hall at the top of Hillary Step.

[3] Krakauer's account notes that by this time, the weather had deteriorated into a full-scale blizzard: "Snow pellets borne on 70 mph [110 km/h] winds stung my face.

Mountain Madness guide Beidleman and clients Klev Schoening, Fox, Madsen, Pittman, and Gammelgaard, along with Adventure Consultant guide Mike Groom and clients Beck Weathers and Yasuko Namba wandered in the blizzard until they could no longer walk, huddling some 20 m (66 ft) from a drop-off of the Kangshung Face.

[citation needed] In the early morning of 11 May, at 04:43, Hall radioed Base Camp and said he was on the South Summit (8,749 m or 28,704 ft), confirming that he had survived the night.

His body was found on 23 May by Ed Viesturs and fellow mountaineers from the IMAX expedition, but was left there as requested by his wife, who said she thought he was "where he'd liked to have stayed".

[29] Later in the day, however, Weathers regained consciousness and walked alone under his own power to the camp, surprising everyone there, though he was still suffering severe hypothermia and frostbite.

Despite receiving oxygen and attempts to rewarm him, Weathers was practically abandoned again the next morning, 12 May, after a storm had collapsed his tent overnight and the other survivors once again thought he had died.

Over the next two days, Weathers was ushered down to Camp II with the assistance of eight healthy climbers from various expeditions, and was evacuated by a daring high-altitude helicopter rescue, one of the highest ever attempted.

The disaster was caused by a combination of events, including: Jon Krakauer has suggested that the use of bottled oxygen and commercial guides, who personally accompanied and took care of all pathmaking, equipment, and important decisions, allowed otherwise unqualified climbers to attempt to summit, thereby leading to dangerous situations and more deaths.

[34]Krakauer also acknowledges that his own presence as a journalist for an important mountaineering magazine may have added pressure to guide clients to the summit despite the growing dangers.

Furthermore, he notes that many of the poor decisions made on 10 May came after two or more days of inadequate oxygen, nourishment, and rest (due to the effects of entering the death zone above 8,000 m or 26,000 ft).

My particular physiology, my years of high-altitude climbing, my discipline, the commitment I make to proper acclimatization, and the knowledge I have of my own capacities have always made me comfortable with this choice.

To this I would add: As a precautionary measure, in the event that some extraordinary demand was placed upon me on summit day, I was carrying one (1) bottle of supplementary oxygen, a mask, and a regulator.