1997 Asian financial crisis

The crisis began in Thailand in July 1997 before spreading to several other countries with a ripple effect, raising fears of a worldwide economic meltdown due to financial contagion.

[2] As the crisis spread, other Southeast Asian countries and later Japan and South Korea saw slumping currencies, devalued stock markets and other asset prices, and a precipitous rise in private debt.

[3][4] Foreign debt-to-GDP ratios rose from 100% to 167% in the four large Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) economies in 1993–96, then shot up beyond 180% during the worst of the crisis.

Brunei, mainland China, Japan, Singapore, Taiwan, and Vietnam were less affected, although all suffered from a general loss of demand and confidence throughout the region.

Although most of the governments of Asia had seemingly sound fiscal policies, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) stepped in to initiate a $40 billion program to stabilize the currencies of South Korea, Thailand, and Indonesia, economies particularly hard hit by the crisis.

After 30 years in power, Indonesian dictator Suharto was forced to step down on 21 May 1998 in the wake of widespread rioting that followed sharp price increases caused by a drastic devaluation of the rupiah.

Only Singapore proved relatively insulated from the shock, but nevertheless suffered serious hits in passing, mainly due to its status as a major financial hub and its geographical proximity to Malaysia and Indonesia.

At the same time, the regional economies of Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore and South Korea experienced high growth rates, of 8–12% GDP, in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

The devaluation of the Chinese renminbi and the Japanese yen, subsequent to the latter's strengthening due to the Plaza Accord of 1985, the raising of U.S. interest rates which led to a strong U.S. dollar, and the sharp decline in semiconductor prices, all adversely affected their growth.

[13] As the U.S. economy recovered from a recession in the early 1990s, the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank under Alan Greenspan began to raise U.S. interest rates to head off inflation.

The resulting large quantities of credit that became available generated a highly leveraged economic climate, and pushed up asset prices to an unsustainable level, particularly those in non-productive sectors of the economy such as real-estate.

When it became clear that the tide of capital fleeing these countries was not to be stopped, the authorities ceased defending their fixed exchange rates and allowed their currencies to float.

The SAPs called on crisis-struck nations to reduce government spending and deficits, allow insolvent banks and financial institutions to fail, and aggressively raise interest rates.

Critics, however, noted the contractionary nature of these policies, arguing that in a recession, the traditional Keynesian response was to increase government spending, prop up major companies, and lower interest rates.

[42] On 11 August 1997, the IMF unveiled a rescue package for Thailand with more than $17 billion, subject to conditions such as passing laws relating to bankruptcy (reorganizing and restructuring) procedures and establishing strong regulation frameworks for banks and other financial institutions.

Unlike Thailand, Indonesia had low inflation, a trade surplus of more than $900 million, huge foreign exchange reserves of more than $20 billion, and a good banking sector.

This practice had worked well for these corporations during the preceding years, as the rupiah had strengthened respective to the dollar; their effective levels of debt and financing costs had decreased as the local currency's value rose.

[47] Although the rupiah crisis began in July and August 1997, it intensified in November when the effects of that summer devaluation showed up on corporate balance sheets.

This led to popular protests culminating in the "EDSA II Revolution", which effected his resignation and elevated Gloria Macapagal Arroyo to the presidency.

While China was unaffected by the crisis compared to Southeast Asia and South Korea, GDP growth slowed sharply in 1998 and 1999, calling attention to structural problems within its economy.

[63]: 53 Lessons learned by policymakers following the financial crisis also became an important factor in China's evolving approach to managing state-owned assets, particularly its foreign exchange reserves, and its creation of sovereign funds beginning with Central Huijin.

The HKMA had recognized that speculators were taking advantage of the city's unique currency-board system, in which overnight rates (HIBOR) automatically increase in proportion to large net sales of the local currency.

[67] It also fully suspended the trading of CLOB (Central Limit Order Book) counters, indefinitely freezing approximately $4.47 billion worth of shares and affecting 172,000 investors, most of them Singaporeans,[68][69][70] which became a political issue between the two countries.

The Japanese yen fell to 147 as mass selling began, but Japan was the world's largest holder of currency reserves at the time, so it was easily defended, and quickly bounced back.

The real GDP growth rate slowed dramatically in 1997, from 5% to 1.6%, and even sank into recession in 1998 due to intense competition from cheapened rivals; also in 1998 the government had to bail out several banks.

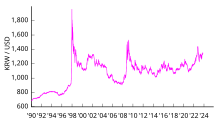

[80] The crisis had significant macroeconomic-level effects, including sharp reductions in values of currencies, stock markets, and other asset prices of several Asian countries.

The economic crisis also led to a political upheaval, most notably culminating in the resignations of President Suharto in Indonesia and Prime Minister General Chavalit Yongchaiyudh in Thailand.

[87] Precrisis levels of income per capita with purchasing power parity were exceeded in 1999 in South Korea, in 2000 in Philippines, in 2002 in Malaysia and Thailand, in 2005 in Indonesia.

[92] The reduction in oil revenue also contributed to the 1998 Russian financial crisis, which in turn caused Long-Term Capital Management in the United States to collapse after losing $4.6 billion in 4 months.

A wider collapse in the financial markets was avoided when Alan Greenspan and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York organized a $3.625 billion bailout.