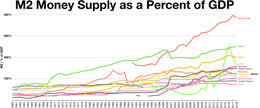

Money supply

There are several ways to define "money", but standard measures usually include currency in circulation (i.e. physical cash) and demand deposits (depositors' easily accessed assets on the books of financial institutions).

[1][2] Money supply data is recorded and published, usually by the national statistical agency or the central bank of the country.

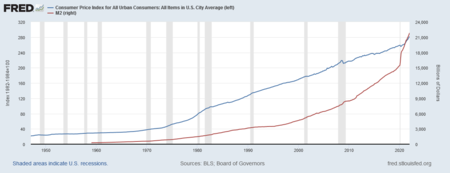

According to the quantity theory supported by the monetarist school of thought, there is a tight causal connection between growth in the money supply and inflation.

Instead they focus on adjusting interest rates, in developed countries normally as part of a direct inflation target which leaves little room for a special emphasis on the money supply.

[5] The different types of money are typically classified as "M"s. The "M"s usually range from M0 (narrowest) to M3 (and M4 in some countries[6]) (broadest), but which "M"s, if any, are actually focused on in central bank communications depends on the particular institution.

In the United States, where the country's currency has a special international role being used in many transactions around the world, legally as well as illegally, the ratio is still more than 8 to 1.

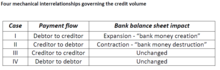

This is a short-hand simplification which disregards several other factors determining commercial banks' reserve-to-deposit ratios and the public's money demand.

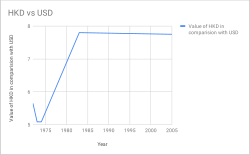

The currency board system ensures that Hong Kong's entire monetary base is backed with US dollars at the linked exchange rate.

Hong Kong also has huge deposits of US dollars, with official foreign currency reserves of 331.3 billion USD as of September 2014[update].

To counter this, the government created the Treasury Tax and Loan (TT&L) program in which any receipts above a certain threshold are redeposited in private banks.

When the Federal Reserve announced in 2005 that they would cease publishing M3 statistics in March 2006, they explained that M3 did not convey any additional information about economic activity compared to M2, and thus, "has not played a role in the monetary policy process for many years."

Common sense tells us that a government central bank creating new money out of thin air depreciates the value of each dollar in circulation.

Indeed, two prominent analytical frameworks in the 20th century both built on this premise: the Keynesian IS-LM model and the monetarist quantity theory of money.

[48] In the traditional version of this model it is assumed that the central bank conducts monetary policy by increasing or decreasing the money supply, which affects interest rates and consequently investment, aggregate demand and output.

The theory builds upon Irving Fisher's equation of exchange from 1911:[50] where In practice, macroeconomists almost always use real GDP to define Q, omitting the role of all other transactions.

[53] The quantity theory was a cornerstone for the monetarists and in particular Milton Friedman, who together with Anna Schwartz in 1963 in a pioneering work documented the relationship between money and inflation in the United States during the period 1867–1960.

[51] Starting in the mid-1970s and increasingly over the next decades, the empirical correlation between fluctuations in the money supply and changes in income or prices broke down, and there appeared clear evidence that money demand (or, equivalently, velocity) was unstable, at least in the short and medium run, which is the time horizon that is relevant to monetary policy.

[20] Concurrently, most central banks in developed countries implemented direct inflation targeting as the foundation of their monetary policy,[54] which leaves little room for a special emphasis on the money supply.

In the United States, the strategy of targeting the money supply was tried under Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker from 1979, but was found to be impractical and later given up.

[55] According to Benjamin Friedman, the number of central banks that actively seek to influence money supply as an element of their monetary policy is shrinking to zero.

[56] Developments in money supply may contain information of the behavior of commercial banks and of the general economic stance which is useful for judging future movements in, say, employment and inflation.