19th century glassmaking in the United States

19th century glassmaking in the United States started slowly with less than a dozen glass factories operating.

After the war, English glassmakers began dumping low priced glassware in the United States, which caused some glass works to go out of business.

A protective tariff and the ingenuity of Boston businessman Deming Jarves helped revive the domestic glass industry.

The 1803 Louisiana Purchase added western territory to the United States and eventually opened new markets for glass products.

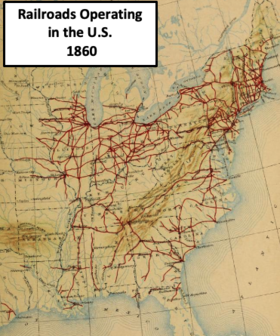

Glass works located along the Ohio River in Pittsburgh and Wheeling were able to take advantage of the nation's waterways to ship their products.

Most of the growth of the nation's railroad industry occurred in the second half of the century, which provided an alternative to waterways for transportation.

This led to mechanical innovations throughout the second half of the century, such as better furnaces for melting the raw materials and better methods of cooling the glass.

By the end of the century, research was being conducted that would make substantial changes to the way bottles and window glass were produced.

Glassmakers use the term "batch" for the sum of all the raw ingredients needed to make a particular glass product.

[10] Annealing was originally conducted in the United States using a kiln that was sealed with the fresh glass inside, heated, and gradually cooled.

[14] Glassmaking methods and recipes were kept secret, and most European countries forbid immigration to the United States by glassworkers.

[20] The problem with wood was that, in good times, a glass factory could consume an amount of forest equal in size to an American football field—in one week.

[22] Alternative fuels such as natural gas and oil did not become available in the United States until the 1870s when they were discovered in Pennsylvania and West Virginia.

[23] In the 1880s, the discovery of natural gas in northwest Ohio combined with its railroad facilities to cause numerous glass factories to relocate there.

[28] When Edward Libbey moved New England Glass Company in 1888, transportation resources were a major factor in his selection of Toledo, Ohio.

[29] Toledo had access to the Great Lakes, the Miami and Erie Canal that connected with the Ohio River, and numerous railroad lines.

[31] The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 opened new markets to glass factories, and those situated on the Ohio River had a waterway to ship their products.

After the war, England began dumping low–priced glass products in the United States while keeping its price for red lead high.

[44] Good quality sand was found in the United States in the Berkshires of Massachusetts, in the Monongahela River in Pennsylvania, and in New Jersey.

[46][Note 3] Deming Jarves considered founder Benjamin Bakewell the "father of the flint–glass [crystal] business in this country".

[50] One historian has called the increased production rate caused by the mechanical pressing machine "the greatest contribution of America to glassmaking, and the most important development since the Romans discovered glassblowing".

[54] Glassmaking on the East Coast of the United States peaked around 1850, as plants shifted to Pittsburgh because of the availability of coal for fuel.

[56] By 1850, the United States had 3,237 free men above age 15 who listed their occupation as part of the glass manufacturing process.

[78] The discovery of natural gas in Ohio and Indiana caused glass factories to either move operations to this source of cheap fuel or begin new companies.

Communities such as Findlay, Fostoria, North Baltimore, Tiffin, and Toledo offered free gas as an incentive for manufacturers to relocate.

[22] The gas supply lasted for only five years, causing most of the glass companies to move closer to better sources of fuel.

[27] In 1888 Edward Libbey moved the New England Glass Company from East Cambridge, Massachusetts, to Toledo, Ohio.

[87] Among new hires in late 1888 was glassblower Michael Joseph Owens, a former worker at the glass works of J. H. Hobbs, Brockunier and Company who wanted to be a foreman.

Leaders in the glassmaking industry described the employment of children, some as young as 10 years old, as essential for certain tasks—and they were cheap labor.

Belgium, England, France, and Germany typically contributed skilled workers—while immigrants from other countries were usually used for the lowest-paying jobs.

Boston and Sandwich Glass Co. ,

Metropolitan Museum of Art

New England Glass Co.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Bakewell, Page & Bakewell

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Metropolitan Museum of Art