2019 European Parliament election in the United Kingdom

Seats would then be allocated proportionally to the share of votes cast for each party or individual candidate in the electoral region using the D'Hondt method of calculation.

The period for withdrawal under Article 50 was first extended, with the unanimous approval of the European Council, until 12 April 2019[27][28] – the deadline for informing the EU of the intention to hold an election.

[29] By early April, the House of Commons had voted again to extend the withdrawal period, and a deadline of 31 October 2019 was agreed between the UK and the Council.

[31] On 7 May, the UK Government announced that it would not be able to obtain ratification in time to prevent the elections, although it still aimed to ratify the withdrawal agreement before October.

[34] The backdrop of ongoing debate around Brexit was expected to be a very significant factor in how people voted, with the election seen by many as a "proxy referendum" on whether the country should leave the EU or not.

suggested that the vote share for the Conservatives and Labour could fall, with voters moving towards a number of pro-Leave or pro-Remain parties,[35] and this did indeed happen.

The Conservative government had made several attempts to get the Withdrawal Agreement that it had negotiated with the EU approved by the House of Commons, which would have allowed for Brexit before the election.

[3] The party's candidates were announced on 18 April, and included former Cabinet minister Andrew Adonis, former MP Katy Clark and the national co-ordinator of campaigning group Momentum Laura Parker.

[50][51] The UK Independence Party selected its three remaining MEPs as candidates, along with social media activist Carl Benjamin and YouTuber Mark Meechan.

Other candidates included in London the entrepreneur Dinesh Dhamija and the former leader of the People's Alliance of Tower Hamlets, Rabina Khan, and former MPs Martin Horwood and Stephen Williams in the South West.

[59] Its candidates included writer Rachel Johnson (sister of Conservative MP Boris Johnson and formerly of the Liberal Democrats), former BBC journalist Gavin Esler,[50] former Conservative MPs Stephen Dorrell and Neil Carmichael, former Labour MEP Carole Tongue, former Labour MPs Roger Casale and Jon Owen Jones, former Liberal Democrat MEP Diana Wallis,[60] and former deputy Prime Minister of Poland Jacek Rostowski.

[62] Jill Evans, Plaid Cymru's sole MEP, stood as the party's lead candidate as part of a full slate for the Wales constituency.

Two of the three sitting MEPs contested the election: Martina Anderson for Sinn Féin and Diane Dodds for the Democratic Unionist Party.

[81] On 27 April, Labour announced that the original leaflet draft was to be redrafted to include details of the party's preparations for a general election, with a referendum if necessary to avoid what it called a "bad Tory deal".

Only one vote was held at the meeting, on an amendment from the TSSA union that sought to commit Labour to a referendum on any Brexit deal, but this was rejected by a what NEC sources called a "clear" margin.

There was renewed criticism surrounding its candidate Carl Benjamin for telling Labour MP Jess Phillips "I wouldn't even rape you" on Twitter in 2016, and producing a satirical video.

[98][99][100] Further controversy came when one of UKIP's sitting MEPs, Stuart Agnew, addressed a pro-apartheid club of expatriate South Africans in London that reportedly had links to the far-right.

[107][108] Vince Cable, the leader of the Liberal Democrats, proposed standing joint candidates with the Greens and Change UK on a common policy of seeking a second referendum on Brexit, but the other parties rejected the idea.

[114] On 15 May, David Macdonald, the lead candidate for Change UK in Scotland, switched to endorsing the Liberal Democrats in order not to split the pro-Remain vote.

[115] On 22 May, Allen said that she and another Change UK MP, Sarah Wollaston, wanted to advise Remain supporters to vote Liberal Democrat outside of London and South East England, but they were overruled by other party members.

[123][124] Change UK (which in early April was still known as the Independent Group) saw the election as an important launchpad for its new party,[7] seeking to turn the ballot into a "proxy referendum" on Brexit.

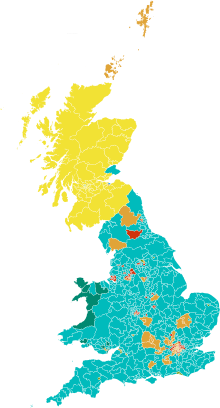

The results saw both Conservatives and Labour losing seats in what The Guardian called a "Brexit backlash" while the Liberal Democrats, Greens and independents made gains.

The Liberal Democrats made the biggest gains which the Lib Dem leader Vince Cable put down to a rejection of the Conservatives and Labour over their Brexit approaches.

[142] May then proposed to bring a new deal to the House of Commons for a vote in early June, which she described as an "improved package of measures",[143] after which she was expected to step down as Prime Minister and leader of the Conservative Party.

Police asked a Scottish fast food outlet, near where a Farage rally was to take place, not to sell milkshakes on the night of the event.

[151] There were several reports on the day of problems encountered by non-UK UK-resident EU citizens not being able to vote because their paperwork had not been processed in time, with opposition politicians raising concerns as to whether there had been systemic failures.

[154] A report by The Guardian after the election found that in many parts of the country there were low levels of completion of UC1 forms, required by UK-resident EU citizens in order for them to vote in the UK.

[195] The chart below depicts opinion polls conducted in Great Britain for the 2019 European Parliament elections in the UK; trendlines are local regressions (LOESS).

[221] Reacting to the results, the Shadow Foreign Secretary Emily Thornberry[222] and Deputy Leader Tom Watson[223] called for the Labour Party to change its policy to supporting a second referendum and remaining in the EU.

[234][235][236] On 4 June 2019, in response to their poor performance in the elections, six of the eleven MPs in Change UK left the group to return to sitting as independents.