2019 Indonesian general election

The presidential election, the fourth in the country's history, used a direct, simple majority system, with incumbent president Joko Widodo, known as Jokowi, running for re-election with senior Muslim cleric Ma'ruf Amin as his running mate against former general Prabowo Subianto and former Jakarta vice governor Sandiaga Uno for a five-year term between 2019 and 2024.

The stated intent of the simultaneous election was to reduce associated costs and minimize transactional politics, in addition to increasing voter turnout.

[8][9] In the 2014 presidential election, Jakarta governor Joko Widodo defeated former general Prabowo Subianto to become the seventh President of Indonesia.

Despite initially having a minority government, Jokowi later managed to secure the support of Golkar and the United Development Party, giving him control of the legislature.

[10][11] In the legislative elections of the same year, former opposition party PDI-P managed to secure the largest share in the DPR, ahead of Golkar and Gerindra.

[12] Despite plans to introduce electronic voting, the DPR in March 2017 announced it would not mandate e-voting in the 2019 elections because of hacking fears and because of the lack of nationwide internet coverage.

[20] Any ethical violations committed by either Bawaslu or the KPU were to be handled by the Elections Organizer Honor Council (Dewan Kehormatan Penyelenggara Pemilu DKPP), which consists of one member from each body and five others recommended by the government.

[28] To run for the presidency, a candidate had to be supported by political parties totalling 20% of the seats in the DPR or 25% of the popular vote in the previous legislative election.[17][18]:Art.

[32] A 4% parliamentary threshold was set for parties to be represented in the DPR, though candidates could still win seats in the regional councils provided they won sufficient votes.

[46] Due to various logistical issues, namely with the distribution of ballot papers, 2,249 polling stations had to conduct follow-up voting.

[50][51] The PKPI's appeal to Bawaslu was rejected, but an 11 April ruling by the National Administrative Court (Pengadilan Tata Usaha Negara) decreed that the party was eligible to contest in the election.

Prabowo's last-minute selection of businessman and Jakarta Vice Governor Sandiaga Uno – close to midnight on that day – was also unexpected.

Other individuals who expressed an intent, received political support, or were touted as prospective presidential candidates included son of former president Yudhoyono and 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial candidate Agus Harimurti Yudhoyono,[79][80] former MPR Speaker Amien Rais,[81][82] Governor of Jakarta and former minister of education and culture Anies Baswedan,[83][84] all of whom subsequently endorsed Prabowo, and incumbent Vice President of Indonesia Jusuf Kalla, who later expressed support for Jokowi.

[91] The first debate held on 17 January 2019, focused on legal, human rights, terrorism and corruption issues, and was moderated by Ira Koesno and Imam Priyono.

Jokowi admitted the difficulty of solving old human rights cases and promising to strengthen law enforcement institutions.

[93] The second debate was held on 17 February 2019, with topics covering energy, food, infrastructure, natural resources and the environment, and was moderated by news presenters Anisha Dasuki and Tommy Tjokro.

[97][98] The third debate, involving the vice-presidential candidates, covered education, health, labour, social affairs and culture, and was held on 17 March 2019.

[102] One example of a major social media-centred campaign, dubbed #2019GantiPresiden emerged, initiated by PKS politician Mardani Ali Sera.

[103] Before the campaign period began, observers had expected rampant hoaxes and fake news coming through social media and WhatsApp.

She was prosecuted as a result and forced to resign from the campaign team, and Prabowo personally apologised for spreading the hoax.

[106] Both sides formed dedicated anti-hoax groups to counterattacks on social media,[87][107] with the Indonesian government holding weekly fake news briefings.

[124][125] By January 2019, the national political parties have collectively reported campaign donations totalling Rp 445 billion (US$31.6 million).

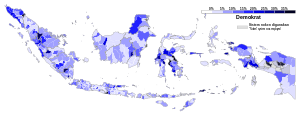

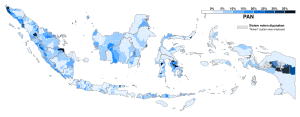

[132] An observer from Cornell University noted Jokowi's dominance in predominantly non-Muslim regions - such as the Hindu Bali and Christian North Sulawesi - despite losing support in heavily Muslim provinces such as Aceh and West Sumatra.

[137] After KPU's official announcement on 21 May, Prabowo stated that he rejected the presidential election results, and would resort to "constitutional legal pathways".

[142] Following the protests, Prabowo's campaign team launched a Constitutional Court lawsuit, with the first hearing scheduled on 18 June 2019.

It was the highest turnout in Indonesian presidential electoral history, in contrast to the trend of an increasing number of abstentions between 2004 and 2014.

[187] Certain areas in Papua also allowed traditional voting procedures where a single village head represented entire communities, resulting in nominal 100% turnouts.

[194] The Supreme Court of Indonesia eventually ruled that the KPU regulation was invalid, allowing convicts to contest in the election.

[206][207] In January 2019, it was rumoured by Yusril Ihza Mahendra that Jokowi was considering releasing Islamist Abu Bakar Ba'asyir due to old age and declining health.

[213][214] Prabowo is known to have close relations with fundamentalist Muslims,[215] with Muhammad Rizieq Shihab of the Islamic Defenders Front being one prominent example.