2020 Minneapolis park encampments

[9] The encampment crisis grew out of civil unrest following the murder of George Floyd, a Black man, while under arrest by a Derek Chauvin, a White officer from the Minneapolis Police Department on Memorial Day on May 25, 2020.

Though homeless people were exempt from curfew orders, volunteers helped about 200 unsheltered persons take up residence at an unoccupied Sheraton Hotel in the city's Midtown neighborhood.

City officials adopted a de-escalation for disbanding camps due to the ongoing civil unrest, and when they attempted to remove tents at non-permitted sites, they faced opposition from a sanctuary movement and protest groups.

[20] A study by the Amherst H. Wilder Foundation, a Saint Paul-based non-profit organization, counted 11,371 people in Minnesota were experiencing homelessness on one night in October 2018.

After detecting the first confirmed case of community spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the state, Governor Tim Walz announced the first of several executive orders to address the COVID-19 pandemic in Minnesota.

[30][31][32] Over a three-night period from May 27 to May 29, Minneapolis sustained extraordinary damage from rioting and looting—largely along a 5-mile (8.0 km) stretch of Lake Street south of downtown[33]—including the demise of the city's third police precinct building, which was overrun by demonstrators and set on fire.

[36] In early April 2020, several people experiencing homelessness took up residence at a small encampment of about a dozen tents in Minneapolis under the Martin Olav Sabo Bridge, near Hiawatha Avenue and the Midtown Greenway bike and pedestrian trail.

[37][38] An initial emergency executive order by Governor Tim Walz emboldened those dwelling at the encampment as it prohibited local government agencies from closing camps.

[38] Officials also wanted to avoid repeat of the "Wall of the Forgotten Natives," a sprawling encampment in 2018 along a Hiawatha Avenue sound barrier that had near-daily occurrences of overdoses and violence.

[37] Walz's revised executive order in early May 2020 allowed encampments to be cleared if they "reached a size or statutes" and posed a health and safety risk to people living there.

[42] People experiencing homelessness were exempt from curfew orders, but worries grew that residents of encampments could be swept up in the unrest and potentially shot at with rubber bullets and tear gas.

[45][46] On July 14, Governor Walz signed an executive order that modified the eviction moratorium to allow local governments to disband camps for safety concerns, illegal activity, and property damage.

[50][58] From July 15 to early August, thirteen additional violent crimes were reported at Powderhorn Park, including multiple assaults, a rape, arson, and injuries from gunfire.

[57] A Star Tribune editorial on August 14 said that "Allowing the camps to grow and attract so much illegal activity has endangered not only neighbors and park users, but also the homeless campers themselves.

[61] In late June, an unpermitted encampment emerged at Peavy Field Park, a 7-acre (2.8 ha) youth recreation area and playground in the city's Ventura Village,[47] that drew criticism for safety concerns.

[62] On September 3, 2020, a group backed by protesters and American Indian Movement advocates re-occupied a site they referred to as the "Wall of Forgotten Natives" near Hiawatha and Franklin avenues in Minneapolis.

Though the city and county had allocated $8 million for three new shelters, including a Native-specific one, advocates were unsatisfied with the response by local officials to the needs of Native homeless persons, and established the camp.

[4] In October, the Mid-Minnesota Legal Aid and the American Civil Liberties Union filed a federal lawsuit to prevent closure of homeless encampments in city parks, but it was dismissed by U.S. District Judge Wilhelmina Wright.

[70] The Minneapolis Sanctuary Movement, one of the organizations coordinating activities at the Sheraton Midtown Hotel and Powderhorn Park encampment described their purpose as being a "community care experiment fighting for housing justice, abolition, and land reclamation by supporting the most impacted people to take the lead".

[71] MplsStPaul magazine described the dynamic as having "lines blurred between sanctuary and rogue activists" who used the circumstances of encampment residents to advance an agenda of social and racial justice, sometimes at the expense of the welfare of unhoused people.

[13] Some neighbors were conflicted about calling law enforcement to respond to violence at the camps, with some instances of reluctance reportedly out of fear that it might subject People of Color to further trauma.

[73] Activists at Powderhorn Park encampment were criticized for not calling paramedics to treat people who overdosed on drugs, and some speculated that deaths or serious drug-related medical injuries could have been prevented had emergency services been rendered.

[13] Activists also drew criticism for not assisting law enforcement investigations of crimes at encampment sites, such as the when people refused to identify the alleged perpetrator who raped a 14-year old at the Powderhorn Park camp.

[8] At encampments, some activists resisted outside help from social service providers and government agencies and insisted that they were self-sufficient,[13] and other volunteers felt that well-intentioned efforts were ultimately doing more harm to vulnerable people.

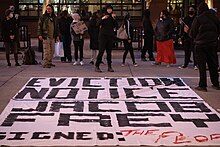

"[49] City officials adopted a de-escalation for disbanding camps due to the ongoing civil unrest, and when they attempted to remove tents at non-permitted sites, they faced opposition from the sanctuary movement and protest groups.

[14] Park encampment closures, even after several health and safety incidents that drew concern from neighborhoods, were the subject of protests by non-resident activist who blocked officials from clearing camps.

[14][62] Some protesters acted as "eviction defense" by boarding heavy machinery that cleared supplies and material from camps, resulting in officers firing pepper spray and making arrests.

[21] The board and park staff collaborated with several agencies to help find available shelter beds, such as Minnesota Interagency Council on Homelessness, and Heading Home Hennepin.

[56] After several sexual assaults occurred at encampments, including of minors, volunteers had to move some women and children to secret, non-permitted campsites in other parts of the city.

[3][82] Incumbent Londel French blamed his failed reelection bid for an at-large board seat due to on his stance on maintaining the Hiawatha Golf Course and support for park encampments.