243 Ida

It was discovered on 29 September 1884 by Austrian astronomer Johann Palisa at Vienna Observatory and named after a nymph from Greek mythology.

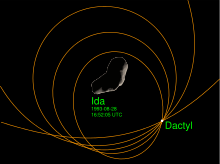

Ida's moon Dactyl was discovered by mission member Ann Harch in images returned from Galileo.

The images returned from Galileo and the subsequent measurement of Ida's mass provided new insights into the geology of S-type asteroids.

Data returned from the flyby pointed to S-type asteroids as the source for the ordinary chondrite meteorites, the most common type found on the Earth's surface.

[16] Ida was recognized as a member of the Koronis family by Kiyotsugu Hirayama, who proposed in 1918 that the group comprised the remnants of a destroyed precursor body.

[17] Ida's reflection spectrum was measured on 16 September 1980 by astronomers David J. Tholen and Edward F. Tedesco as part of the eight-color asteroid survey (ECAS).

These improved the measurement of Ida's orbit around the Sun and reduced the uncertainty of its position during the Galileo flyby from 78 to 60 km (48 to 37 mi).

These were selected as targets in response to a new NASA policy directing mission planners to consider asteroid flybys for all spacecraft crossing the belt.

[37] The composition of S-types was uncertain before the Galileo flybys, but was interpreted to be either of two minerals found in meteorites that had fallen to the Earth: ordinary chondrite (OC) and stony-iron.

The Galileo images also led to the discovery that space weathering was taking place on Ida, a process which causes older regions to become more red in color over time.

[9] This field is so weak that an astronaut standing on its surface could leap from one end of Ida to the other, and an object moving in excess of 20 m/s (70 ft/s) could escape the asteroid entirely.

[30] This constricted shape is consistent with Ida being made of two large, solid components, with loose debris filling the gap between them.

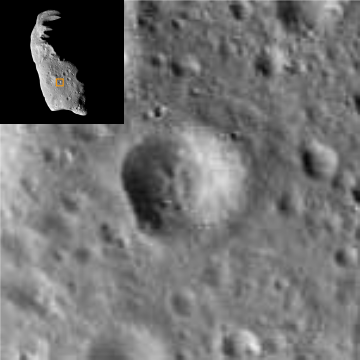

[9] Ida's surface appears heavily cratered and mostly gray, although minor color variations mark newly formed or uncovered areas.

Ida is covered by a thick layer of regolith, loose debris that obscures the solid rock beneath.

One is a prominent 40 km (25 mi) ridge named Townsend Dorsum that stretches 150 degrees around Ida's surface.

[57] Ida is one of the most densely cratered bodies yet explored in the Solar System,[31][44] and impacts have been the primary process shaping its surface.

[51] The ejecta from this collision is distributed discontinuously over Ida[38] and is responsible for the large-scale color and albedo variations across its surface.

[62] An exception to the crater morphology is the fresh, asymmetric Fingal, which has a sharp boundary between the floor and wall on one side.

[64] The ejecta excavated by impacts is deposited differently on Ida than on planets because of its rapid rotation, low gravity and irregular shape.

[12] The composition of the interior has not been directly analyzed, but is assumed to be similar to OC material based on observed surface color changes and Ida's bulk density of 2.27–3.10 g/cm3.

[10][43][11] The calculated maximum moment of inertia of a uniformly dense object the same shape as Ida coincides with the spin axis of the asteroid.

[57] Ida's axis of rotation precesses with a period of 77 thousand years, due to the gravity of the Sun acting upon the nonspherical shape of the asteroid.

[71] However, this is inconsistent with the estimated age of the Ida–Dactyl system of less than 100 million years;[72] it is unlikely that Dactyl, due to its small size, could have escaped being destroyed in a major collision for longer.

The difference in age estimates may be explained by an increased rate of cratering from the debris of the Koronis parent body's destruction.

Dactyl was found on 17 February 1994 by Galileo mission member Ann Harch, while examining delayed image downloads from the spacecraft.

[36] It is marked by more than a dozen craters with a diameter greater than 80 m (260 ft), indicating that the moon has suffered many collisions during its history.

[16] At least six craters form a linear chain, suggesting that it was caused by locally produced debris, possibly ejected from Ida.

[71] The Eos and Koronis families ... are entirely of type S, which is rare at their heliocentric distances ...Nearly a month after a successful photo session, the Galileo spacecraft last week finished radioing to Earth a high-resolution portrait of the second asteroid ever to be imaged from space.

Known as 243 Ida, the asteroid was photographed from an average distance of just 3,400 kilometers some 3.5 minutes before Galileo's closest approach on Aug. 28.The chondrites fall naturally into five composition classes, of which three have very similar mineral contents, but different proportions of metal and silicates.

These three classes, referred to collectively as the ordinary chondrites, contain quite different amounts of metal.When Zeus was born, Rhea entrusted the guardianship of her son to the Dactyls of Ida, who are the same as those called Curetes.