3D film

A combination of these elements into animated stereoscopic photography may have been conceived early on, but for decades it did not become possible to capture motion in real-time photographic recordings due to the long exposure times necessary for the light-sensitive emulsions that were used.

[14][15] On August 11, 1877, the Daily Alta newspaper announced a project by Eadward Muybridge and Leland Stanford to produce sequences of photographs of a running horse with 12 stereoscopic cameras.

"[17] Dr. Phipson, a correspondent for British news in a French photography magazine, relayed the concept, but renamed the device "Kinétiscope" to reflect the viewing purpose rather than the recording option.

He believed the system to be uneconomical due to its need for special theatres instead of the widely available movie screens, and he did not like that it seemed only suitable for stage productions and not for "natural" films.

The earliest confirmed 3D film shown to an out-of-house audience was The Power of Love, which premiered at the Ambassador Hotel Theater in Los Angeles on September 27, 1922.

The following March he exhibited a remake of his 1895 short film L'Arrivée du Train, this time in anaglyphic 3D, at a meeting of the French Academy of Science.

What aficionados consider the "golden era" of 3D began in late 1952 with the release of the first color stereoscopic feature, Bwana Devil, produced, written and directed by Arch Oboler.

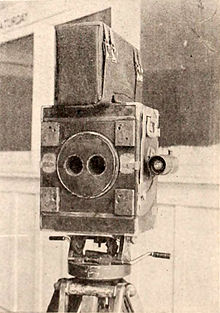

Gunzberg, who built the rig with his brother Julian, Friend Baker and Lothrop Worth, shopped it without success to various studios before Oboler used it for this feature, which went into production with the title, The Lions of Gulu.

[37] The critically panned film was nevertheless highly successful with audiences due to the novelty of 3D, which increased Hollywood interest in 3D during a period that had seen declining box-office admissions.

The success of these two films proved that major studios now had a method of getting filmgoers back into theaters and away from television sets, which were causing a steady decline in attendance.

John Ireland, Joanne Dru and Macdonald Carey starred in the Jack Broder color production Hannah Lee, which premiered on June 19, 1953.

[citation needed] Despite these shortcomings and the fact that the crew had no previous experience with the newly built camera rig, luck was on the cinematographer's side, as many find the 3D photography in the film is well shot and aligned.

Although it was more expensive to install, the major competing realism process was wide-screen, but two-dimensional, anamorphic, first utilized by Fox with CinemaScope and its September premiere in The Robe.

The film, adapted from the popular Cole Porter Broadway musical, starred the MGM songbird team of Howard Keel and Kathryn Grayson as the leads, supported by Ann Miller, Keenan Wynn, Bobby Van, James Whitmore, Kurt Kasznar and Tommy Rall.

Even though Polaroid had created a well-designed "Tell-Tale Filter Kit" for the purpose of recognizing and adjusting out of sync and phase 3D,[43] exhibitors still felt uncomfortable with the system and turned their focus instead to processes such as CinemaScope.

The film was shot in 2-D, but to enhance the bizarre qualities of the dream-world that is induced when the main character puts on a cursed tribal mask, these scenes went to anaglyph 3D.

Arch Oboler once again had the vision for the system that no one else would touch, and put it to use on his film entitled The Bubble, which starred Michael Cole, Deborah Walley, and Johnny Desmond.

As with Bwana Devil, the critics panned The Bubble, but audiences flocked to see it, and it became financially sound enough to promote the use of the system to other studios, particularly independents, who did not have the money for expensive dual-strip prints of their productions.

Other sci-fi/fantasy films were released as well including Metalstorm: The Destruction of Jared-Syn and Treasure of the Four Crowns, which was widely criticized for poor editing and plot holes, but did feature some truly spectacular closeups.

3D releases after the second craze included The Man Who Wasn't There (1983), Silent Madness and the 1985 animated film Starchaser: The Legend of Orin, whose plot seemed to borrow heavily from Star Wars.

The Walt Disney Company also began more prominent use of 3D films in special venues to impress audiences with Magic Journeys (1982) and Captain EO (Francis Ford Coppola, 1986, starring Michael Jackson) being notable examples.

Expo II was announced as being the locale for the world premiere of several films never before seen in 3D, including The Diamond Wizard and the Universal short, Hawaiian Nights with Mamie Van Doren and Pinky Lee.

Other "re-premieres" of films not seen since their original release in stereoscopic form included Cease Fire!, Taza, Son of Cochise, Wings of the Hawk, and Those Redheads From Seattle.

As Brandon Gray of Box Office Mojo notes, "In each case, 3D's more-money-from-fewer-people approach has simply led to less money from even fewer people.

"[69] Film critic Mark Kermode, a noted detractor of 3D, has surmised that there is an emerging policy of distributors to limit the availability of 2D versions, thus "railroading" the 3D format into cinemas whether the paying filmgoer likes it or not.

For example, for the 3D re-release of the 1993 film The Nightmare Before Christmas, Walt Disney Pictures scanned each original frame and manipulated them to produce left-eye and right-eye versions.

[79] Anaglyph images were the earliest method of presenting theatrical 3D, and the one most commonly associated with stereoscopy by the public at large, mostly because of non-theatrical 3D media such as comic books and 3D television broadcasts, where polarization is not practical.

A drawback of this method is the need for each person viewing to wear expensive, electronic glasses that must be synchronized with the display system using a wireless signal or attached wire.

This is not necessarily a usage problem; for some types of displays which are already very bright with poor grayish black levels, LCD shutter glasses may actually improve the image quality.

"[106] Nolan also criticised that shooting on the required digital video does not offer a high enough quality image[107] and that 3D cameras cannot be equipped with prime (non-zoom) lenses.