3-sphere

For example, when traveling on a 3-sphere, you can go north and south, east and west, or along a 3rd set of cardinal directions.

In coordinates, a 3-sphere with center (C0, C1, C2, C3) and radius r is the set of all points (x0, x1, x2, x3) in real, 4-dimensional space (R4) such that The 3-sphere centered at the origin with radius 1 is called the unit 3-sphere and is usually denoted S3: It is often convenient to regard R4 as the space with 2 complex dimensions (C2) or the quaternions (H).

This view of the 3-sphere is the basis for the study of elliptic space as developed by Georges Lemaître.

What this means, in the broad sense, is that any loop, or circular path, on the 3-sphere can be continuously shrunk to a point without leaving the 3-sphere.

The Poincaré conjecture, proved in 2003 by Grigori Perelman, provides that the 3-sphere is the only three-dimensional manifold (up to homeomorphism) with these properties.

For example, a Dehn filling with slope 1/n on any knot in the 3-sphere gives a homology sphere; typically these are not homeomorphic to the 3-sphere.

Unlike the 2-sphere, the 3-sphere admits nonvanishing vector fields (sections of its tangent bundle).

One way to think of the fourth dimension is as a continuous real-valued function of the 3-dimensional coordinates of the 3-ball, perhaps considered to be "temperature".

Likewise, we may inflate the 2-sphere, moving the pair of disks to become the northern and southern hemispheres.

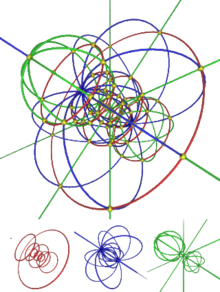

Stereographic projection of a 3-sphere (again removing the north pole) maps to three-space in the same manner.

Returning to our picture of the unit two-sphere sitting on the Euclidean plane: Consider a geodesic in the plane, based at the origin, and map this to a geodesic in the two-sphere of the same length, based at the south pole.

Since the open unit disk is homeomorphic to the Euclidean plane, this is again a one-point compactification.

The exponential map for 3-sphere is similarly constructed; it may also be discussed using the fact that the 3-sphere is the Lie group of unit quaternions.

Due to the nontrivial topology of S3 it is impossible to find a single set of coordinates that cover the entire space.

Note that, for any fixed value of ψ, θ and φ parameterize a 2-sphere of radius

For unit radius another choice of hyperspherical coordinates, (η, ξ1, ξ2), makes use of the embedding of S3 in C2.

In complex coordinates (z1, z2) ∈ C2 we write This could also be expressed in R4 as Here η runs over the range 0 to π/2, and ξ1 and ξ2 can take any values between 0 and 2π.

Another convenient set of coordinates can be obtained via stereographic projection of S3 from a pole onto the corresponding equatorial R3 hyperplane.

(Note that the numerator and denominator commute here even though quaternionic multiplication is generally noncommutative).

Because the set of unit quaternions is closed under multiplication, S3 takes on the structure of a group.

It turns out that the only spheres that admit a Lie group structure are S1, thought of as the set of unit complex numbers, and S3, the set of unit quaternions (The degenerate case S0 which consists of the real numbers 1 and −1 is also a Lie group, albeit a 0-dimensional one).

It has the property that the absolute value of a quaternion q is equal to the square root of the determinant of the matrix image of q.

Using our Hopf coordinates (η, ξ1, ξ2) we can then write any element of SU(2) in the form Another way to state this result is if we express the matrix representation of an element of SU(2) as an exponential of a linear combination of the Pauli matrices.

It is seen that an arbitrary element U ∈ SU(2) can be written as The condition that the determinant of U is +1 implies that the coefficients α1 are constrained to lie on a 3-sphere.

Writing in the American Journal of Physics,[5] Mark A. Peterson describes three different ways of visualizing 3-spheres and points out language in The Divine Comedy that suggests Dante viewed the Universe in the same way; Carlo Rovelli supports the same idea.