Equal temperament

That resulting smallest interval, 1/12 the width of an octave, is called a semitone or half step.

In Western countries the term equal temperament, without qualification, generally means 12 TET.

The standard pitch has not always been 440 Hz; it has varied considerably and generally risen over the past few hundred years.

[4] Some wind instruments that can easily and spontaneously bend their tone, most notably trombones, use tuning similar to string ensembles and vocal groups.

Because the perceived identity of an interval depends on its ratio, this scale in even steps is a geometric sequence of multiplications.

(An arithmetic sequence of intervals would not sound evenly spaced and would not permit transposition to different keys.)

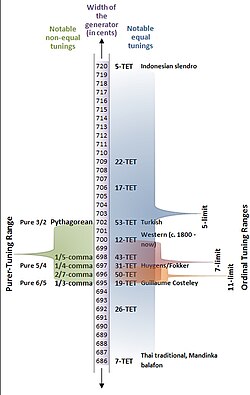

This logarithmic scale makes comparison of different tuning systems easier than comparing ratios, and has considerable use in ethnomusicology.

This simplifies and generalizes discussion of pitch material within the temperament in the same way that taking the logarithm of a multiplication reduces it to addition.

The two figures frequently credited with the achievement of exact calculation of equal temperament are Zhu Zaiyu (also romanized as Chu-Tsaiyu.

Kuttner, a critic of giving credit to Zhu,[5] it is known that Zhu "presented a highly precise, simple and ingenious method for arithmetic calculation of equal temperament mono-chords in 1584" and that Stevin "offered a mathematical definition of equal temperament plus a somewhat less precise computation of the corresponding numerical values in 1585 or later."

[6](p200) Kenneth Robinson credits the invention of equal temperament to Zhu[7][b] and provides textual quotations as evidence.

[8] In 1584 Zhu wrote: Kuttner disagrees and remarks that his claim "cannot be considered correct without major qualifications".

[5] Kuttner proposes that neither Zhu nor Stevin achieved equal temperament and that neither should be considered its inventor.

[10] Chinese theorists had previously come up with approximations for 12 TET, but Zhu was the first person to mathematically solve 12 tone equal temperament,[11] which he described in two books, published in 1580[12] and 1584.

[16] Some of the first Europeans to advocate equal temperament were lutenists Vincenzo Galilei, Giacomo Gorzanis, and Francesco Spinacino, all of whom wrote music in it.

[17][18][19][20] Simon Stevin was the first to develop 12 TET based on the twelfth root of two, which he described in van de Spiegheling der singconst (c. 1605), published posthumously in 1884.

[21] Plucked instrument players (lutenists and guitarists) generally favored equal temperament,[22] while others were more divided.

This allowed enharmonic modulation, new styles of symmetrical tonality and polytonality, atonal music such as that written with the 12-tone technique or serialism, and jazz (at least its piano component) to develop and flourish.

In the following table, the sizes of various just intervals are compared to their equal-tempered counterparts, given as a ratio as well as cents.

[27] According to Morton, A South American Indian scale from a pre-instrumental culture measured by Boiles in 1969 featured 175 cent seven-tone equal temperament, which stretches the octave slightly, as with instrumental gamelan music.

[37] Their step sizes: Alpha and beta may be heard on the title track of Carlos's 1986 album Beauty in the Beast.

In this section, semitone and whole tone may not have their usual 12 EDO meanings, as it discusses how they may be tempered in different ways from their just versions to produce desired relationships.

Let the number of steps in a semitone be s, and the number of steps in a tone be t. There is exactly one family of equal temperaments that fixes the semitone to any proper fraction of a whole tone, while keeping the notes in the right order (meaning that, for example, C, D, E, F, and F♯ are in ascending order if they preserve their usual relationships to C).

Starting on the subdominant F (in the key of C) there are three perfect fifths in a row—F–C, C–G, and G–D—each a composite of some permutation of the smaller intervals T T t s .

The sequence of intervals s, c, and κ can be repeatedly appended to itself into a greater spiral of 12 fifths, and made to connect at its far ends by slight adjustments to the size of one or several of the intervals, or left unmodified with occasional less-than-perfect fifths, flat by a comma.

Various equal temperaments can be understood and analyzed as having made adjustments to the sizes of and subdividing the three intervals— T , t , and s , or at finer resolution, their constituents s , c , and κ .