Enharmonic equivalence

Similarly, written intervals, chords, or key signatures are considered enharmonic if they represent identical pitches that are notated differently.

The predominant tuning system in Western music is twelve-tone equal temperament (12 TET), where each octave is divided into twelve equivalent half steps or semitones.

Prior to this modern use of the term, enharmonic referred to notes that were very close in pitch — closer than the smallest step of a diatonic scale — but not quite identical.

Enharmonic equivalents can be used to improve the readability of music, as when a sequence of notes is more easily read using sharps or flats.

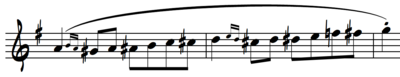

This is primarily a notational convenience, since D-flat minor would require many double-flats and be difficult to read: The concluding passage of the slow movement of Schubert's final piano sonata in B♭ (D960) contains a dramatic enharmonic change.

In other tuning systems, such pairs of written notes do not produce an identical pitch, but can still be called "enharmonic" using the older, original sense of the word.

On a piano tuned in equal temperament, both G♯ and A♭ are played by striking the same key, so both have a frequency Such small differences in pitch can skip notice when presented as melodic intervals; however, when they are sounded as chords, especially as long-duration chords, the difference between meantone intonation and equal-tempered intonation can be quite noticeable.

Enharmonically equivalent pitches can be referred to with a single name in many situations, such as the numbers of integer notation used in serialism and musical set theory and as employed by MIDI.