6th Massachusetts Militia Regiment

In the years immediately preceding the war and during its first enlistment, the regiment consisted primarily of companies from Middlesex County.

[3] Shortly after South Carolina issued its Declaration of Secession, Massachusetts Governor John A. Andrew anticipated imminent civil war and issued an order on January 16, 1861, to the ten existing Massachusetts units of peacetime militia to immediately reorganize and prepare for active service.

[5] On April 15, 1861, three days after Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter, President Lincoln issued a call for 75,000 volunteers to serve in putting down the insurrection.

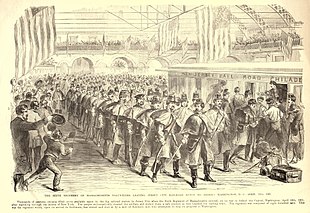

[9] On April 19, 1861, the 6th Massachusetts boarded train cars in Philadelphia in the early morning hours and departed for Washington via Baltimore.

Cars were drawn individually along rails on Pratt Street by horsepower to Camden Station on the west side of Baltimore's Inner Harbor, where the trains were reassembled.

The initial cars encountered little resistance but soon a growing crowd of Baltimore citizens became increasingly agitated by the passing transports filled with troops.

[12] The crowd barricaded the rails by dumping cartloads of sand and dragging anchors from the nearby docks across them thus preventing further cars from passing.

After crossing the Pratt Street Bridge, which had been partially dismantled by the crowd, Follansbee ordered his men to march at the "double-quick."

[14] Seventeen-year-old Private Luther C. Ladd, a factory worker from Lowell, was hit in the head by a piece of scrap iron that was thrown from a rooftop and fractured his skull.

[19] A formation of approximately 50 officers of the Baltimore Police eventually placed themselves between the rioters and the militiamen, allowing the 6th Massachusetts to proceed to Camden Station.

At the time a clerk in the U.S. Patent Office, Barton gained her first experience in caring for wounded soldiers as she tended to injured men of the 6th Massachusetts.

"[26] The 6th Massachusetts remained in Washington until May 5, when they were assigned to garrison a key railroad relay station about 15 miles outside of Baltimore at Elkridge.

[27] The regiment's return to Boston at the close of their 90-day term was delayed slightly by special request of Major General Nathaniel P. Banks.

In light of the recent Union defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run, in which the 6th Massachusetts did not participate, he asked the regiment voluntarily remain at Elkridge another week in the event of a Confederate advance on Washington.

The unit received a very different welcome in Baltimore during their second term and were given a large reception with food and drink and much cheering from the citizens of the city.

[33] They served garrison and picket duty in the vicinity of Suffolk, occasionally taking part in reconnaissance expeditions to the Blackwater River (which represented the boundary between the Union occupied counties of southeast Virginia and Confederate territory of the interior) and engaged in minor skirmish actions.

The 6th Massachusetts formed a peripheral part of the Expedition against Franklin, a joint effort of the U.S. Army and Navy to dislodge a growing force of Confederates threatening the Union garrison at Suffolk.

[35] Although the 6th Massachusetts did not see any combat during their first expedition, and many members recalled it as tedious, the sight of ambulances carrying dead and wounded from the battle made a strong impression on the new recruits.

[36] During a second expedition to the Blackwater on December 11, 1862, the 6th Massachusetts was lightly engaged near Zuni, Virginia, and lost their first casualty in battle during their second enlistment—2nd Lieutenant Robert G.

Confederates opposed this Union advance on January 30 during the Battle of Deserted House in an isolated location about ten miles west of Suffolk.

[41] In early 1863, Major General James Longstreet was given command of the Confederate Department of North Carolina and Southern Virginia.

For 22 days, the regiment engaged in frequent exchanges of fire with opposing forces though no significant assault was made by the Confederates.

[41] In the middle of the battle, when the 6th Massachusetts was driven back, Private Joseph S.G. Sweatt of Company C perceived that several of his comrades had been hit and were left in the woods.

According to his citation, "When ordered to retreat, this soldier turned and rushed back to the front, in the face of heavy fire from the enemy, in an endeavor to rescue his wounded comrades, remaining by them until overpowered and taken prisoner."

[33] In May 1864, Major General Ulysses S. Grant removed fresh troops from the defensive fortifications of Washington and transferred them into the field to strengthen the Army of the Potomac.

To man defenses around the capital in their place, and to relieve regiments at various northern fortifications, Lincoln issued a call for 500,000 troops to serve a brief term of 100 days.

The regiment relieved the 157th Ohio Infantry and commenced garrison and guard duty over the 7,000 Confederate prisoners of war held at Fort Delaware.

The regimental historian recorded that many members of the unit remember their time at Fort Delaware as extremely pleasant.

[33] Shortly after the bodies of Privates Luther Ladd and Addison Whitney were brought home to Lowell, Massachusetts, after the Baltimore Riot, city officials began planning the construction of a monument honoring their sacrifice and memorializing the first casualties of the Civil War.

The monument was to be dedicated on April 19, 1865, on the anniversary of the Baltimore Riot, but the ceremonies were delayed due to the assassination of President Lincoln.