New York City draft riots

Conditions in the city were such that Major General John E. Wool, commander of the Department of the East, said on July 16 that "Martial law ought to be proclaimed, but I have not a sufficient force to enforce it.

During the 1840s and 1850s, journalists had published sensational accounts, directed at the white working class, dramatizing the evils of interracial socializing, relationships, and marriages.

[7] The Democratic Party's Tammany Hall political machine had been working to enroll immigrants as U.S. citizens so they could vote in local elections and had strongly recruited Irish.

Newly elected New York City Republican Mayor George Opdyke was mired in profiteering scandals in the months leading up to the riots.

The Emancipation Proclamation of January 1863 alarmed much of the white working class in New York, who feared that freed slaves would migrate to the city and add further competition to the labor market.

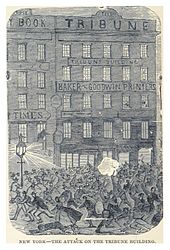

At 10 am, a furious crowd of around 500, led by the volunteer firemen of Engine Company 33 (known as the "Black Joke"), attacked the assistant Ninth District provost marshal's office, at Third Avenue and 47th Street, where the draft was taking place.

[14] The 19th Company/1st Battalion US Army Invalid Corps which was part of the Provost Guard tried to disperse the mob with a volley of gunfire but were overwhelmed and suffered over 14 injured with 1 soldier missing (believed killed).

The mayor's residence on Fifth Avenue was spared by words of Judge George Gardner Barnard, and the crowd of about 500 turned to another location of pillage.

[11] The mob beat, tortured and/or killed numerous black civilians, including one man who was attacked by a crowd of 400 with clubs and paving stones, then lynched, hanged from a tree and set alight.

Rioters went into the streets in search of "all the negro porters, cartmen and laborers" to attempt to remove all evidence of a black and interracial social life from the area near the docks.

White dockworkers attacked and destroyed brothels, dance halls, boarding houses, and tenements that catered to black people.

[7] Heavy rain fell on Monday night, helping to abate the fires and sending rioters home, but the crowds returned the next day.

[7][17] Governor Horatio Seymour arrived on Tuesday and spoke at City Hall, where he attempted to assuage the crowd by proclaiming that the Conscription Act was unconstitutional.

General John E. Wool, commander of the Eastern District, brought approximately 800 soldiers and Marines in from forts in New York Harbor, West Point, and the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

[13] The situation improved July 15 when assistant provost-marshal-general Robert Nugent received word from his superior officer, Colonel James Barnet Fry, to postpone the draft.

[22] Violence by longshoremen against black men was especially fierce in the docks area:[7] West of Broadway, below Twenty-sixth, all was quiet at 9 o'clock last night.

Late in the afternoon, a negro was dragged out of his house in West Twenty-seventh street, beaten down on the sidewalk, pounded in a horrible manner, and then hanged to a tree.

[24] Among the murdered black people was the seven-year-old nephew of Bermudian First Sergeant Robert John Simmons of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, whose account of fighting in South Carolina, written on the approach to Fort Wagner July 18, 1863, was to be published in the New York Tribune on December 23, 1863 (Simmons having died in August of wounds received in the attack on Fort Wagner).

Herbert Asbury, the author of the 1928 book Gangs of New York, upon which the 2002 film was based, puts the figure much higher, at 2,000 killed and 8,000 wounded,[25] a number that some dispute.

The orphans at the asylum were first put under siege, then the building was set on fire, before all those who attempted to escape were forced to walk through a "beating line" of white rioters holding clubs.

As a result of the violence against them, hundreds of black people left New York, including physician James McCune Smith and his family, moving to Williamsburg, Brooklyn, or New Jersey.

[7] The white elite in New York organized to provide relief to black riot victims, helping them find new work and homes.

[29] While the rioting mainly involved the white working class, middle and upper-class New Yorkers had split sentiments on the draft and use of federal power or martial law to enforce it.

[30] In December 1863, the Union League Club recruited more than 2,000 black soldiers, outfitted and trained them, honoring and sending men off with a parade through the city to the Hudson River docks in March 1864.

General Edward R. S. Canby[note 2] Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton authorized five regiments from Gettysburg, mostly federalized state militia and volunteer units from the Army of the Potomac, to reinforce the New York City Police Department.