8th Division (Australia)

[4] While it had initially been planned for the 8th Division to deploy to the Middle East, as the possibility of war with Japan loomed, the 22nd Brigade was sent instead to Malaya on 2 February 1941 to undertake garrison duties there following a British request for more troops.

[8] As war broke out in the Pacific Japanese forces based in Vichy French-controlled Indochina quickly overran Thailand and invaded Malaya.

Japanese forces met stiff resistance from III Corps of the Indian Army and British units in northern Malaya, but Japan's superiority in air power,[10] tanks and infantry tactics forced the British and Indian units, who had very few tanks and remained vulnerable to isolation and encirclement,[11][12] back along the west coast towards Gemas and on the east coast towards Endau.

On 26 January, the 2/18th Battalion launched an ambush around the Nithsdale and Joo Lye rubber plantations, which resulted in heavy Japanese casualties and briefly held up their advance allowing the 22nd Brigade time to withdraw south.

By 31 January, the last British Commonwealth forces had left Malaya, and engineers blew a hole 70 feet (21 m) wide in the causeway.

[19] The Allied commander, Lieutenant-General Arthur Percival, gave Major General Gordon Bennett's 8th Division the task of defending the prime invasion points on the north side of the island, in a terrain dominated by mangrove swamps and forest.

[21] From vantage points across the straits, including the Sultan of Johore's palace, as well as aerial reconnaissance and infiltrators, the Japanese commander, General Tomoyuki Yamashita and his staff gained an excellent knowledge of the Allied positions.

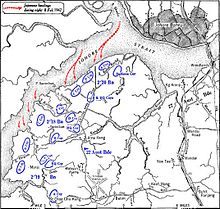

[23] At 8.30 pm on 8 February, Australian machine gunners opened fire on vessels carrying a first wave of 16 infantry battalions, totalling around 4,000 Japanese troops, towards Singapore Island, concentrating on the positions occupied by the 3,000-strong 22nd Brigade.

[27] Around dawn on 9 February a further 10,000 Japanese troops landed,[26] and as it became clear that the 22nd Brigade was being overrun and it was decided to form a secondary defensive line to the east of Tengah airfield and north of Jurong.

However, the next day, the Japanese Imperial Guard made a botched landing in the northwest, suffering severe casualties from drowning and burning oil in the water, as well as Australian mortars and machine guns.

[30] That same day, communication problems and misunderstandings, led to the withdrawal of two Indian brigades, and loss of the crucial Kranji–Jurong ridge through the western side of the island.

[32][33] Nevertheless, the British Commonwealth forces steadily lost more ground, with Japanese penetrating to within five miles of Singapore urban centre, by 10 February capturing Bukit Timah.

The Australians established a defensive perimeter to the north-west of the city centre around Tanglin Barracks, while preparations were made to mount a final stand.

[40] By the morning of 15 February, the Japanese had broken through the last line of defence in the north and food and some kinds of ammunition had begun to run out.

[43] A small number were able to escape POW camps and continue fighting either by making their way back to Australia,[44] or as members of guerrilla units (for example Jock McLaren).

[51][52] According to Smith, Bennett described his own troops as "wobbly" and Brigadier Harold Taylor, commander of the 22nd Brigade, told his men they were a "disgrace to Australia and the AIF.

Amidst the onslaught, fighting took place around Simpson Harbour, Keravia Bay and Raluana Point,[62] while a company of troops from the 2/22nd and NGVR fought to hold the Japanese around Vulcan Beach.

[64] Following this, the Lark Force commander, Lieutenant Colonel John Scanlan, ordered the Australian soldiers and civilians to split into small groups and retreat through the jungle.

[63] At least 800 soldiers and civilian prisoners of war lost their lives on 1 July 1942, when the ship on which they were sent from Rabaul to Japan, the Montevideo Maru, was sunk off the north coast of Luzon by the US submarine USS Sturgeon.

[72] The existing Royal Netherlands East Indies Army garrison, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Kapitz, consisted of 2,800 Indonesian colonial troops,[73] with Dutch officers.

[73] Although the Japanese ground forces were numerically not much bigger than the Allies, they had overwhelming superiority in air support, naval and field artillery, and tanks.

The Australian and Dutch governments agreed that, in the event of Japan entering World War II, Australia would provide forces to reinforce West Timor.

Sparrow Force joined about 650 Dutch East Indies and Portuguese troops and was supported by the 12 Lockheed Hudson light bombers of No.

Additional Australian support staff arrived at Kupang on 12 February, including Brigadier William Veale, who was to be the senior Allied officer on Timor.

The bombing, hampered by AA guns and a squadron of US Army Air Forces fighters based in Darwin, intensified during February.

[88] With his soldiers running low on ammunition, exhausted and carrying 132 men with serious wounds, and without communications to Sparrow Force HQ Leggatt eventually acceded to a Japanese invitation to surrender.

[90] Veale and the Sparrow Force HQ force—including some members of the 2/40th and about 200 Dutch East Indies troops—continued eastward across the border,[91] and eventually joined the 2/2 Independent Company.

[84] The 2/40th effectively ceased to exist, its survivors being absorbed into the 2/2nd and subsequently took part in the guerrilla campaign that was waged on Timor in the following months, before being evacuated in December 1942.

[87] After a journey lasting several weeks, traversing the Strait of Malacca, Sumatra and then Java, following his escape from Malaya, Bennett arrived in Melbourne on 2 March 1942.

[101] During the fighting in Malaya, Singapore, Ambon, Timor and Rabaul the 8th Division lost over 10,000 men, including 2,500 killed in action, with this figure representing two-thirds of all deaths sustained by the Australian Army in the Pacific.