Accelerator mass spectrometry

[2] Other advantages of AMS include its short measuring time as well as its ability to detect atoms in extremely small samples.

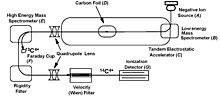

The pre-accelerated ions are usually separated by a first mass spectrometer of sector-field type and enter an electrostatic "tandem accelerator".

After this stage, no background is left, unless a stable (atomic) isobar forming negative ions exists (e.g. 36S if measuring 36Cl), which is not suppressed at all by the setup described so far.

Thanks to the high energy of the ions, these can be separated by methods borrowed from nuclear physics, like degrader foils and gas-filled magnets.

Individual ions are finally detected by single-ion counting (with silicon surface-barrier detectors, ionization chambers, and/or time-of-flight telescopes).

There are other ways in which AMS is achieved; however, they all work based on improving mass selectivity and specificity by creating high kinetic energies before molecule destruction by stripping, followed by single-ion counting.

Alvarez and Robert Cornog of the United States first used an accelerator as a mass spectrometer in 1939 when they employed a cyclotron to demonstrate that 3He was stable; from this observation, they immediately and correctly concluded that the other mass-3 isotope, tritium (3H), was radioactive.

His paper was the direct inspiration for other groups using cyclotrons (G. Raisbeck and F. Yiou, in France) and tandem linear accelerators (D. Nelson, R. Korteling, W. Stott at McMaster).

Compared to other radiocarbon dating methods, AMS requires smaller sample sizes (about 50 mg), while yielding extensive chronologies.