A History of British Birds (Yarrell book)

William Yarrell's A History of British Birds was first published as a whole in three volumes in 1843, having been serialised, three sheets (=48 pages)[1] every two months, over the previous six years.

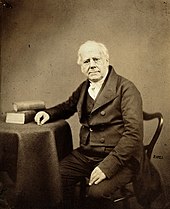

Yarrell, a newsagent without university education, corresponded widely with eminent naturalists such as Thomas Pennant and Coenraad Jacob Temminck, and consulted the writings of scientists including Carl Linnaeus, to collect accurate information on the hundreds of species illustrated in the work.

[2] Yarrell had the free time and income to indulge his hobbies of shooting and fishing, and started to show an interest in rare birds, sending some specimens to the engraver and author Thomas Bewick.

[4] Its approach, however, was significantly different in the extensiveness of Yarrell's correspondence and in the increased emphasis on scientific accuracy made possible by the rapid advance in ornithological knowledge in the nineteenth century.

During the six years of writing, with the regular publication of three-sheet instalments of his Birds, many people across Britain and Europe sent him descriptions, observations and specimens for him to include, and the book is full of references to such contributions.

Yarrell explicitly states in his Preface that During these six years many occurrences of rare birds, and of some that were even new to Britain, became known to me, either by the communications of private friends and correspondents, or from the examination of the various periodical works which give publicity to such events.

For the ringed plover, for example, Sven Nilsson speaks for Sweden and the Baltic coast; Mr Hewitson for Norway; Carl Linnaeus for Lapland; a Mr Scoresby for Iceland and Greenland; the zoologist Thomas Pennant for Russia and Siberia; the archaeologist Charles Fellows[a] for Asia Minor [Turkey], and Coenraad Jacob Temminck for Japan.

Like Bewick, Yarrell's sections begin with a large wood engraving, depicting the species against a more or less realistic background: that of the Egyptian vulture shows a pyramid and a pair of laden camels.

As well as straightforward details of each bird, Yarrell adds many stories, chosen from his own experience, from his correspondents, or from often recently published accounts, to enliven the description of each species according to his taste.

For example, the "Fulmar Petrel" quotes John Macgillivray's article "in a recent number of the Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal", describing a visit to St Kilda in June 1840, for a page and a half.

It begins: This bird exists here in almost incredible numbers, and to the natives is by far the most important of the productions of the island ... [They] daily risk their lives in its pursuit.

The Fulmar breeds on the face of the highest precipices, and only on such as are furnished with small grassy shelves, every spot on which, above a few inches in extent, is occupied with one or more of its nests ...

The Fulmar flies with great buoyancy and considerable rapidity, and when at sea is generally seen skimming along the surface of the waves at a slight elevation ... Macgillivray is similarly relied upon for accounts of the pink-footed goose and the goosander as far as the Hebrides are concerned.

But he constantly provides accurate stories that inform and entertain the reader: Mr Jesse .. says:— A gentleman had a Corn Crake brought to him by his dog, to all appearance quite dead.

Having laid it again upon the ground and retired to some distance, the bird in about five minutes warily raised its head, looked round, and decamped at full speed.In addition to the work of collating descriptions and commissioning drawings and engravings, Yarrell also made his own scientific observations of certain topics, including the description of the trachea of several species, and a detailed account, occupying seven pages, of the skull, jaw, musculature, and feeding behaviour of the common crossbill, Loxia curvirostra.

Yarrell introduces his special interest in this bird's head as follows: The peculiar formation and direction of the parts of the beak in the Crossbill, its anomalous appearance, as well as the particular and powerful manner in which it is exercised, had long excited in me a desire to examine the structure of an organ so curious, and the kindness of a friend supplied me with the means.Yarrell at once goes on to explain that the crossbills are unique in making use of "any lateral motion of the mandibles, and it is my object here to describe the bony structure and muscles by which this peculiar and powerful action is obtained."

Yarrell then adds an observation of his own, and contradicts an opinion of a famous scientist: "Notwithstanding Buffon's assertion to the contrary, they can pick up and eat the smallest seeds ... so perfect and useful is this singular instrument."

Yarrell concludes by writing "I have never met with a more interesting, or more beautiful example, of the adaptation of means to an end, than is to be found in the beak, the tongue, and their muscles, in the Crossbill".

[8] The most expensive part of producing illustrated books in the nineteenth century was the hand colouring of printed plates,[9] mainly by young women.

Simon Holloway suggests that Fussell and the engravers Charles Thompson and sons probably made all the illustrations for the first three editions of Yarrell's Birds.

Thomas R. Forbes, in his biographical paper on Yarrell, writes that "All [editions of Birds] are outstanding because of the author's clear, narrative style, accuracy, careful scholarship, and unassuming charm.

In well chosen prose, Yarrell provides synonymy, generic characters, a description with measurements, local and general distribution and a life history including nidification and eggs and arrival and departure times for each species.

[1] In Ornithology in Scotland, Yarrell's Birds is described as "written by an Englishman and illustrated in a manner calculated to attract the non-scientific ornithologist right at the opening of the era of the great Victorian naturalists".

[1] The fourth edition was revised and extended by the ornithologists Alfred Newton and Howard Saunders, with some additional illustrations bringing the total number of engravings up to 564.

Yarrell's tail-pieces, small engravings fitted into spaces at the ends of articles, follow the tradition established by Bewick,[20] but differ in rarely being whimsical.