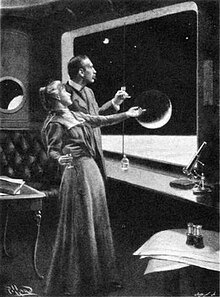

A Honeymoon in Space

British aristocrat Rollo Lenox Smeaton Aubrey, the Earl of Redgrave, is in love with an American woman by the name of Lilla Zaidie Rennick, who is engaged to marry another man.

[1][2]: 150 [3] Redgrave intercepts the ocean liner carrying Zaidie to her fiancé in England in the Astronef, a spaceship he built from designs made by her deceased father, Dr.

[3][4][5]: 112, 265 Redgrave lures Zaidie—along with her chaperone—on board the Astronef and then kidnaps her by taking off at great speed to Washington, D.C., where he delivers a top secret alliance treaty from Britain to the president.

[4][5]: 244 [9] The life found here is more primitive near the equator, and grows increasingly more advanced as the voyagers approach the planet's south pole, starting with marine reptiles resembling those of Earth's Mesozoic era and culminating with cavepeople.

[20] The six instalments were:[1][21] These stories were later assembled alongside additional material that had been cut for publication in Pearson's Magazine—roughly a quarter of the total length of the work, consisting of the earliest portion of the story—and published in novel form as A Honeymoon in Space in 1901.

[18] E. F. Bleiler, in the 1990 reference work Science-Fiction: The Early Years, calls Griffith "historically important, but a bad writer" and dismisses the story as infantile.

[3] Don D'Ammassa, in his 2005 Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, calls the book "a kitchen sink space adventure whose scientific basis was unsound even for its time", while acknowledging that he nevertheless found the depictions of the Martians and Venusians interesting.

[4] No generalization in terms of specific influences seems adequate or significant; rather, one may judge Griffith to exemplify the often conflicting attitudes with which the popular imagination tried to comprehend the universe and technology that had already destroyed the old orders but had not yet established a satisfying new basis for the twentieth century.

[9] Neil Barron, in the 1981 edition of Anatomy of Wonder: A Critical Guide to Science Fiction, says that the book is historically important inasmuch as it serves as a record of what the other planets were imagined to be like at the time.

[27] Science fiction critic Robert Crossley [Wikidata], in the 2011 non-fiction book Imagining Mars: A Literary History, categorizes the book among a group of works from around the turn of the century which he dubs "masculinist fantasies"—works characterized by standing in fundamental opposition to works of feminist science fiction such as the 1893 novel Unveiling a Parallel: A Romance by Alice Ilgenfritz Jones and Ella Robinson Merchant [ca].

[8] Mars in particular exemplifies the Darwinian theme: the Martians encountered in the story belong to the last surviving race that outcompeted the others as the planet's available resources dwindled.

[11][12][28]: 378–379 David Darling and Karl Siegfried Guthke [de] both identify Venus and Ganymede as exceptions to the overarching scheme of worlds in various evolutionary stages from early rise to final decline.

[12][28]: 378–379 Life on Venus has progressed not in terms of biology but theology, achieving a higher spiritual state; both authors draw parallels with the later portrayal of Venusians in C. S. Lewis' 1943 novel Perelandra.

[28]: 369–370 On the topic of Darwinian evolution in A Honeymoon in Space, Stableford suggests that "had Griffith read his Flammarion more attentively, or even his Wells, he might have done much more" instead of mainly representing aliens as variations on humans.

[9] The unease many in this time period felt towards the implications of Darwin's teachings as they relate to humanity is reflected in the book: Zaidie objects to Darwin's book title The Descent of Man, saying "We—especially the women—have ascended from that sort of thing, if there is any truth in the story at all; though personally, I must say I prefer dear old Mother Eve", and thereby rejecting the biological explanation for humanity's origin in favour of the Biblical one.

[8] Thomas D. Clareson, in the 1984 reference work Science Fiction in America, 1870s–1930s: An Annotated Bibliography of Primary Sources, likewise writes that "The idea of the supremacy of the Anglo-Saxon people is the cornerstone of [Griffith's] thinking".

[7] Crossley comments that the explanation given in the story for the Martians speaking English is an example of the kind of Anglocentric cultural attitudes that had previously been the subject of satire in Wells' The War of the Worlds.

[2]: 159 Iwan Rhys Morus [Wikidata], in the 2022 book How the Victorians Took Us to the Moon, writes that the exploration of space in the story reveals the influence of imperialism through the apparent desire to conquer alien worlds.

On the subject, Morus notes that the description of the fictional spaceship bears more resemblance to the warships of the era than to either existing airships or the powered flying machines that were being developed at the time.