A New System of Domestic Cookery

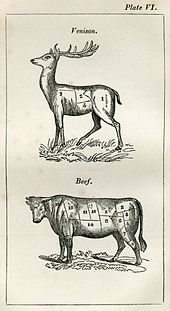

Where those books consist almost wholly of recipes, Mrs Rundell begins by explaining techniques of economy ("A minute account of the annual income and the times of payment should be kept in writing"[5]), how to carve, how to stew, how to season, to "Look clean, be careful and nice in work, so that those who have to eat might look on",[6] how to choose and use steam-kettles and the bain-marie, the meanings of foreign terms like pot-au-feu ("truly the foundation of all good cookery"[7]), all the joints of meat, the "basis of all well-made soups",[8] so it is page 65 before actual recipes begin.

We cannot speak in praise of its receipts for the higher kinds of cookery, but we dare say that they will be very much admired by precisely that class of gastronomes whose judgement is worth nothing.

[13]The review concluded that "though we have no respect for Mrs. Rundell's salmis, we cordially admire her practical good sense, and applaud her for the production of a useful book" which had been "the pattern of all that have since been published.

"[13] By 1841 the Quarterly Literary Advertiser was able to give as the "Opinions of the Press", on the 64th edition, paragraphs of favourable reviews from the Worcestershire Guardian ("the standard work of reference in every private family in English society"), the Hull Advertiser ("most valuable advice upon all household matters"), the Derby Reporter ("a complete guide ... suited to the present advanced state of the art"), Keane's Bath Journal ("it leaves no room to any rival"), the Durham Advertiser ("No housekeeper ought to be without this book"), the Brighton Gazette ("if further proof be wanting, it may be found in the fact that Mrs. Rundell received from her publisher, Mr. Murray, no less a sum than Two Thousand Guineas for her labour!!

"), the Aylesbury News ("the peculiarity of the present work is its scientific preface, and an attention to economy as well as taste in giving its directions"), the Bristol Mirror ("far surpasses all its predecessors, and continues to be the best treatise extant concerning the art"), the Midland Counties Herald ("ought to be in the hands of every lady who does not consider it vulgar to look after the affairs of her own household"), the Inverness Herald ("enriched with the latest improvements in gastronomic science") and The Scotsman,[14] which said The sixty-fourth edition!

... Of the additions made by her successor [Emma Roberts], ... she appears to have brought a large amount of experience in the art of cookery to the task, and her name alone is a sufficient guarantee for the utility and excellence of her new receipts.

The compiler, Mrs. Rundell, had spent the early part of her life in India, and the last edition of the work is enriched with many receipts of Indian cookery.

[1] Elizabeth Grice, writing in The Daily Telegraph, similarly calls Rundell "a Victorian domestic goddess", though without "Nigella's sexual frisson, or Delia's uncomplicated kitchen manners".

"[16] She says that compared to Eliza Acton "who could write better" (as in her 1845 book, Modern Cookery for Private Families), and the "ubiquitous" Mrs Beeton, Rundell "has unfairly slipped from view".

[16] Alan Davidson, in the Oxford Companion to Food writes that "It did not include many novel features, although it did have one of the first English recipes for tomato sauce.