A Tale of a Tub

A satire on the Roman Catholic and Anglican churches and English Dissenters, it was famously attacked for its profanity and irreligion, starting with William Wotton, who wrote that it made a game of "God and Religion, Truth and Moral Honesty, Learning and Industry" to show "at the bottom [the author's] contemptible Opinion of every Thing which is called Christianity.

[2][3] One commentator complained that Swift must be "a compulsive cruiser of Dunghils … Ditches, and Common-Shores with a great Affectation [sic] for every thing that is nasty.

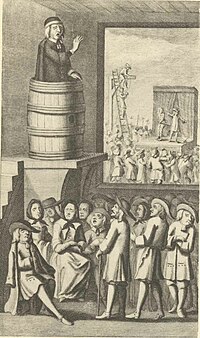

This part of the book is a pun on "tub", which Alexander Pope says was a common term for a Dissenter's pulpit, and a reference to Swift's own position as a clergyman.

[10] Swift's explanation for the title of the book is that the Ship of State was threatened by a whale (specifically, the Leviathan of Thomas Hobbes) and the new political societies (the Rota Club is mentioned).

His book is intended to be a tub that the sailors of state (the nobles and ministers) might toss over the side to divert the attention of the beast (those who questioned the government and its right to rule).

The book is not one that could occupy the Leviathan, or preserve the Ship of State, so Swift may be intensifying the dangers of Hobbes's critique rather than allaying them to provoke a more rational response.

Some, such as the discussion of ears or of wisdom being like a nut, a cream sherry, a cackling hen, etc., are outlandish and require a militantly aware and thoughtful reader.

[13] Swift writes A Tale of a Tub in the guise of a narrator who is excited and gullible about what the new world has to offer, and feels that he is quite the equal or superior of any author who ever lived because he, unlike them, possesses 'technology' and newer opinions.

Swift seemingly asks the question of what a person with no discernment but with a thirst for knowledge would be like, and the answer is the narrator of Tale of a Tub.

If he was not a particular fan of the aristocracy, he was a sincere opponent of democracy, which was often viewed then as the sort of "mob rule" that led to the worst abuses of the English Interregnum.

Swift's satire was intended to provide a genuine service by painting the portrait of conspiracy minded and injudicious writers.

[14] Born of English parents in Ireland, Jonathan Swift was working as Sir William Temple's secretary at the time he composed A Tale of a Tub (1694–1697).

Swift's general polemic concerns an argument (the "Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns") that had been over for nearly ten years by the time the book was published.

Among others, two men who took the side opposing Temple were Richard Bentley (classicist and editor) and William Wotton (critic).

Some critics have seen in Swift's reluctance to praise mankind in any age proof of his misanthropy, and others have detected in it an overarching hatred of pride.

By 1713–14, however, the Tory government had fallen, and Swift was made Dean of Saint Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin—an appointment he considered an exile.

Both in the narrative sections and the digressions, the single human flaw that underlies all the follies Swift attacks is over-figurative and over-literal reading, both of the Bible and of poetry and political prose.

Within the "tale" sections of the book, Peter, Martin, and Jack fall into bad company (becoming the official religion of the Roman empire) and begin altering their coats (faith) by adding ornaments.

[19] As has recently been argued by Michael McKeon, Swift might best be described as a severe sceptic, rather than a Whig, Tory, empiricist, or religious writer.

In the "Apology for the &c." (added in 1710), Swift explains that his work is, in several places, a "parody," which is where he imitates the style of persons he wishes to expose.

In the historical background to the period of 1696–1705, the most important political events might be the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, the Test Act, and the English Settlement or Glorious Revolution of 1688–1689.

It was common enough for Puritans and other dissenters to disrupt church services, to accuse political leaders of being the anti-Christ, and to move the people toward violent schism, riots, and peculiar behaviour including attempts to set up miniature theocracies.

Anne was rumoured to be immoderately stupid and was supposedly governed by her friend, Sarah Churchill, wife of the Duke of Marlborough.

He claims, both in "The Apology for the &c." and in a reference in Book I of Gulliver's Travels, to have written the Tale to defend the crown from the troubles of the monsters besetting it.

The print revolution had meant that people were gathering under dozens of banners, and political and religious sentiments previously unspoken were now rallying supporters.

It was in this edition that the Notes and the "Apology for the &c." ("&c." was Swift's shorthand for Tale of a Tub: Nutt was supposed to expand the abbreviation out to the book's title but did not do so; the mistake was left) were added, which many contemporary readers and authors found a heating up of an already savage satire.

Swift was such a powerful champion of Tory, or anti-Whig, causes that fans of the Tale were eager to attribute the book to another author from nearly the day of its publication.

Consequently, there were rumours of various people as the author of the work—Jonathan Swift then being not largely known except for his work in the House of Lords for the passage of the First Fruits and Fifths bill for tithing.

He said that, when the publication initially took place, Swift was abroad in Ireland and "that little Parson-cousin of mine" "affected to talk suspiciously, as if he had some share in it.

Robert Hendrickson notes in his book British Literary Anecdotes that "Swift was always partial to his strikingly original The Tale of a Tub (1704).