Sermons of Jonathan Swift

[27] Swift summarises this message with the Parable of the Talents as he says: God sent us into the world to obey His commands, by doing as much good as our abilities will reach, and as little evil as our many infirmities will permit.

[33] Paul's words, "that there should be no schism in the body", were important in the formation of this sermon, and served as part of Swift's encouragement to the people of Ireland to follow the same religion.

[43] Regardless of the innuendo about Roman religious tyranny or comparisons to early Christian history, the sermon is given, as Ehrenpreis claims, with an "air of simplicity, frankness, common sense, and spontaneity" that "disarms the listener.

[45] He introduces this claim when he says: This nation of ours hath, for an hundred years past, been infested by two enemies, the Papists and fanatics, who, each in their turns, filled it with blood and slaughter, and, for a time, destroyed both the Church and government.

The Papists, God be praised, are, by the wisdom of our laws, put out of all visible possibility of hurting us; besides, their religion is so generally abhorred, that they have no advocates or abettors among Protestants to assist them.

[25] For example: And others again, whom God had formed with mild and gentle dispositions, think it necessary to put a force upon their own tempers, by acting a noisy, violent, malicious part, as a means to be distinguished.

But its being found amongst the same papers; and the hand, though writ somewhat better, bearing a great similitude to the Dean's, made him willing to lay it before the public, that they might judge whether the style and manner also does not render it still more probable to be his.

[54] Swift alludes to such people when he says: Such witnesses are those who cannot hear an idle intemperate expression, but they must immediately run to the magistrate to inform; or perhaps wrangling in their cups over night, when they were not able to speak or apprehend three words of common sense, will pretend to remember everything the next morning, and think themselves very properly qualified to be accusers of their brethren.

"[59] He explains this: And, it is a mistake to think, that the most hardened sinner, who oweth his possessions or titles to any such wicked arts of thieving, can have true peace of mind, under the reproaches of a guilty conscience, and amid the cries of ruined widows and orphans.

[37] He emphasises this point when he explains the importance of meekness and modesty: Since our blessed Lord, instead of a rich and honourable station in this world, was pleased to choose his lot among men of the lower condition; let not those, on whom the bounty of Providence hath bestowed wealth and honours, despise the men who are placed in a humble and inferior station; but rather, with their utmost power, by their countenance, by their protection, by just payment of their honest labour, encourage their daily endeavours for the support of themselves and their families.

[60] The solution to fixing the misery of the Irish people is: to found a school in every parish of the kingdom, for teaching the meaner and poorer sort of children to speak and read the English tongue, and to provide a reasonable maintenance for the teachers.

This would, in time, abolish that part of barbarity and ignorance, for which our natives are so despised by all foreigners: this would bring them to think and act according to the rules of reason, by which a spirit of industry, and thrift, and honesty would be introduced among them.

I desire you will all weigh and consider what I have spoken, and, according to your several stations and abilities, endeavour to put it in practice;[61]Some critics have seen Swift as hopeless in regards to actual change for Ireland.

[63] The rich could never change from their absentee landlord mentality that has stripped Ireland of its economic independence, and that is why Swift spends the majority of his sermon discussing the poor.

Swift states: Many men come to church to save or gain a reputation; or because they will not be singular, but comply with an established custom; yet, all the while, they are loaded with the guilt of old rooted sins.

These men can expect to hear of nothing but terrors and threatenings, their sins laid open in true colours, and eternal misery the reward of them; therefore, no wonder they stop their ears, and divert their thoughts, and seek any amusement rather than stir the hell within them.

"[65]He describes these people as: Men whose minds are much enslaved to earthly affairs all the week, cannot disengage or break the chain of their thoughts so suddenly, as to apply to a discourse that is wholly foreign to what they have most at heart.

[68] Although the Anglican mass emphasises the Epistle to the Romans,[68] Swift relied on Corinthians in order to combat religious schismatic tendencies in a similar manner to his criticism of dissenters in "On Mutual Subjection".

[69] However, a second aspect of I Corinthians also enters into the sermon; Swift relies on it to promote the idea that reason can be used to comprehend the world, but "excellency of speech" is false when it comes to knowledge about the divine.

"[72] It is unsure when the sermon was actually given, but some critics suggest it was read immediately following the publication of Swift's Letter to the Whole People of Ireland[73] while others place it in October 1724.

By the love of our country, I do not mean loyalty to our King, for that is a duty of another nature, and a man may be very loyal, in the common sense of the word, without one grain of public good in his heart.

[77] Beyond basic "self-esteem" issues, Swift used the sermon to reinforce the moral arguments incorporated into the Drapier's Letters with religious doctrine and biblical authority.

[82] Swift emphasises both when he says: I know very well, that the Church hath been often censured for keeping holy this day of humiliation, in memory of that excellent king and blessed martyr, Charles I, who rather chose to die on a scaffold, than betray the religion and liberties of his people, wherewith God and the laws had entrusted him.

[25] Swift concludes his sermon with: On the other side, some look upon kings as answerable for every mistake or omission in government, and bound to comply with the most unreasonable demands of an unquiet faction; which was the case of those who persecuted the blessed Martyr of this day from his throne to the scaffold.

Between these two extremes, it is easy, from what hath been said, to choose a middle; to be good and loyal subjects, yet, according to your power, faithful assertors of your religion and liberties; to avoid all broachers and preachers of newfangled doctrines in the Church; to be strict observers of the laws, which cannot be justly taken from you without your own consent: In short, 'to obey God and the King, and meddle not with those who are given to change.

His reasoning, however powerful, and indeed unanswerable, convinces the understanding, but is never addressed to the heart; and, indeed, from his instructions to a young clergyman, he seems hardly to have considered pathos as a legitimate ingredient in an English sermon.

Occasionally, too, Swift's misanthropic habits break out even from the pulpit; nor is he altogether able to suppress his disdain of those fellow mortals, on whose behalf was accomplished the great work of redemption.

In short, he tears the bandages from their wounds, like the hasty surgeon of a crowded hospital, and applies the incision knife and caustic with salutary, but rough and untamed severity.

Upon all subjects of morality, the preacher maintains the character of a rigid and inflexible monitor; neither admitting apology for that which is wrong, nor softening the difficulty of adhering to that which is right; a stern stoicism of doctrine, that may fail in finding many converts, but leads to excellence in the few manly minds who dare to embrace it.

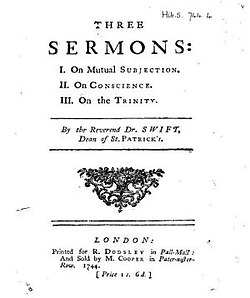

In treating the doctrinal points of belief, (as in his Sermon upon the Trinity,) Swift systematically refuses to quit the high and pre-eminent ground which the defender of Christianity is entitled to occupy, or to submit to the test of human reason, mysteries which are placed, by their very nature, far beyond our finite capacities.