Aaron

According to Abrahamic religions, Aaron[note 1] (/ˈɛərən/ AIR-ən or /ˈærən/ ARR-ən)[2] was a Jewish prophet, a high priest, and the elder brother of Moses.

The Hebrew Bible relates that, unlike Moses, who grew up in the Egyptian royal court, Aaron and his elder sister Miriam remained with their kinsmen in the northeastern region of the Nile Delta.

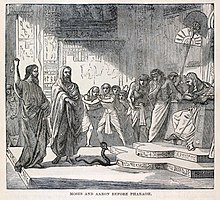

When Moses first confronted the Egyptian king about the enslavement of the Israelites, Aaron served as his brother's spokesman to the Pharaoh (Exodus 7:1).

Part of the Law given to Moses at Sinai granted Aaron the priesthood for himself and his male descendants, and he became the first High Priest of the Israelites.

[25] From here on in Exodus, Leviticus and Numbers, Joshua appears in the role of Moses' assistant while Aaron functions instead as the first high priest.

The books of Exodus, Leviticus and Numbers maintain that Aaron received from God a monopoly over the priesthood for himself and his male descendants.

[30][1] God commissioned the Aaronide priests to distinguish the holy from the common and the clean from the unclean, and to teach the divine laws (the Torah) to the Israelites.

[38] Most scholars think the Torah reached its final form early in this period, which may account for Aaron's prominence in Exodus, Leviticus and Numbers.

During the prolonged absence of Moses on Mount Sinai, the people provoked Aaron to make a golden calf.

[43] For example, in rabbinic sources[44][45] and in the Quran, Aaron was not the idol-maker and upon Moses' return begged his pardon because he felt mortally threatened by the Israelites.

[46] On the day of Aaron's consecration, his oldest sons, Nadab and Abihu, were burned up by divine fire because they offered "strange" incense.

[43] The Torah generally depicts the siblings, Moses, Aaron, and Miriam, as the leaders of Israel after the Exodus, a view also reflected in the biblical Book of Micah.

[48] Numbers 12, however, reports that on one occasion, Aaron and Miriam complained about Moses' exclusive claim to be the LORD's prophet.

When the rebels were punished by being swallowed up by the earth,[50] Eleazar, the son of Aaron, was commissioned to take charge of the censers of the dead priests.

[15][59] There is a significant amount of travel between these two points, as the itinerary in Numbers 33:31–37 records seven stages between Moseroth (Mosera) and Mount Hor.

These tensions, particularly evident during the Persian and early Hellenistic periods, are seen in conflicting narratives about Moses’s and Aaron’s roles.

"[72] Under the influence of the priesthood that shaped the destinies of the nation under Persian rule, a different ideal of the priest was formed, according to Malachi 2:4-7, and the prevailing tendency was to place Aaron on a footing equal with Moses.

[71] In fulfillment of the promise of peaceful life, symbolized by the pouring of oil upon his head,[73] Aaron's death, as described in the aggadah, was of a wonderful tranquility.

[63] Accompanied by Moses, his brother, and by Eleazar, his son, Aaron went to the summit of Mount Hor, where the rock suddenly opened before him and a beautiful cave lit by a lamp presented itself to his view.

The cave closed behind Moses as he left; and he went down the hill with Eleazar, with garments rent, and crying: "Alas, Aaron, my brother!

[63] A voice was then heard saying: "The law of truth was in his mouth, and iniquity was not found on his lips: he walked with me in righteousness, and brought many back from sin.

[77][63] Moses and Aaron met in gladness of heart, kissing each other as true brothers,[78] and of them it is written: "Behold how good and how pleasant [it is] for brethren to dwell together in unity!

Then the Shekhinah spoke the words: "Behold the precious ointment upon the head, that ran down upon the beard of Aaron, that even went down to the skirts of his garment, is as pure as the dew of Hermon.

"[87][better source needed] This is further illustrated by the tradition[88] that Aaron was an ideal priest of the people, far more beloved for his kindly ways than was Moses.

"[63][96] In the Eastern Orthodox and Maronite churches, Aaron is venerated as a saint whose feast day is shared with his brother Moses and celebrated on September 4.

[108][109] Aaron appears paired with Moses frequently in Jewish and Christian art, especially in the illustrations of manuscript and printed Bibles.

Aaron also appears in scenes depicting the wilderness Tabernacle and its altar, as already in the third-century frescos in the synagogue at Dura-Europos in Syria.

An eleventh-century portable silver altar from Fulda, Germany depicts Aaron with his censor, and is located in the Musée de Cluny in Paris.

[111] Christian artists sometimes portray Aaron as a prophet[112] holding a scroll, as in a twelfth-century sculpture from the Cathedral of Noyon in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and often in Eastern Orthodox icons.