Abbas the Great

With the help of these newly created layers in Iranian society (initiated by his predecessors but significantly expanded during his rule), Abbas managed to eclipse the power of the Qizilbash in the civil administration, the royal house, and the military.

These actions, as well as his reforms of the Iranian army, enabled him to fight the Ottomans and Uzbeks and reconquer Iran's lost provinces, including Kakheti, whose people he subjected to widescale massacres and deportations.

[11] Abbas' mother, Khayr al-Nisa Begum, was the daughter of Mir Abdollah II, a local ruler in the province of Mazandaran from the Mar'ashi dynasty who claimed descent from the fourth Shi'ia imam, Ali ibn Husayn Zayn al-Abidin.

[30] The Takkalu tribe eventually seized the power in Qazvin and proceeded to purge a number of prominent Shamlu members, among them being the mother and father of Ali-Qoli Khan.

This angered Ali-Qoli Khan and, just as the queen had predicted, in 1581, he took arms against the crown and made his ward, the ten-year-old Abbas, the figurehead of a rebellion in Khorasan by proclaiming him Shah of Iran.

[37] As they rode along the Silk Road, Qizilbash amirs from the powerful Takkalu, Afshar and Zul al-Qadr tribes, who controlled many of the key towns on the way, came to pledge their allegiance.

But they gave up when crowds of citizens and soldiers, anxious to avoid fighting, came out onto the streets and voiced their support for Abbas, who rode into the capital beside Murshid Qoli Khan in late-September 1587.

To counterbalance their power and as a decisive answer to this problem, Abbas turned to the newly introduced members of Iranian society (an initiative put in place by Shah Tahmasp I) the ghulams (a word literally meaning "slaves").

For Tahmasp, the problem revolved around the military tribal elite of the empire, the Qizilbash, who believed that physical proximity to and control of a member of the immediate Safavid family guaranteed spiritual advantages, political fortune and material advancement.

[52] Therefore, between 1540 and 1555, Tahmasp conducted a series of invasions of the Caucasus region which provided battle experience for his soldiers, as well as leading to the capture of large numbers of Christian Circassian and Georgian slaves (30,000 in just four raids).

Although the first slave soldiers would not be organised until Abbas' reign, during Tahmasp's time Caucasians would already become important members of the royal household, the harem and in the civil and military administration.

[55][56] Learning from his grandfather, Abbas (who had been used by the vying Qizilbash factions during his youth)[50] decided to encourage this new (Caucasian) grouping in Iranian society, as he realised that he must impose his authority on the Qezelbāš or remain their puppet.

Many of those deported from the Caucasus settled in various regions of Iran and became craftsmen, farmers, cattle breeders, traders, soldiers, generals, governors and peasants within Iranian society.

[71] He created a standing army of many thousands of ghulams (always conscripted from ethnic Georgians and Circassians), and to a much lesser extent Iranians, to fight alongside the traditional, feudal force provided by the Qizilbash.

Abbas learnt that the Ottoman plan was to invade Iran via Azerbaijan, take Tabriz then move on to Ardabil and Qazvin, which they could use as bargaining chips in exchange for other territories.

[92] Profiting from the confusion surrounding the accession of the new Ottoman Sultan Murad IV, he pretended to be making a pilgrimage to the Shi'ite shrines of Kerbala and Najaf, but used his army to seize Baghdad.

[93] However, Abbas was then distracted by a rebellion in Georgia in 1624 led by Giorgi Saakadze thus allowing an Ottoman force to besiege Baghdad, but the Shah came to its relief the next year and defeated the Turkish army decisively.

In 1606, Abbas had appointed these Georgians onto the thrones of Safavid vassals Kartli and Kakheti, at the behest of Kartlian nobles and Teimuraz's mother Ketevan; both seemed like malleable youths.

[67] At this point war broke out, Iranian armies invaded the two territories in March 1614, and the two allied kings subsequently sought refuge in the Ottoman vassal Imeretia.

[95] In 1619 Abbas appointed the loyal Simon II (or Semayun Khan) as a puppet ruler of Kakheti, while placing a series of his own governors to rule over districts where the rebellious inhabitants were mostly located.

Abbas counterattacked in June, won the subsequent war and dethroned Teimuraz, but lost half his army at the hands of the Georgians and was forced to accept Kartli and Kakheti only as vassal states while abandoning his plans to eliminate Christians from the area.

As Roger Savory writes, "Not since the development of Baghdad in the eighth century A.D. by the Caliph al-Mansur had there been such a comprehensive example of town-planning in the Islamic world, and the scope and layout of the city centre clearly reflect its status as the capital of an empire.

[114] Abbas' painting studios (of the Isfahan school established under his patronage) created some of the finest art in modern Iranian history, by such illustrious painters as Reza Abbasi and Muhammad Qasim.

[95] Abbas' tolerance towards most Christians was part of his policy of establishing diplomatic links with European powers to try to enlist their help in the fight against their common enemy, the Ottoman Empire.

The idea of such an anti-Ottoman alliance was not a new one – over a century before, Uzun Hassan, then ruler of part of Iran, had asked the Venetians for military aid – but none of the Safavids had made diplomatic overtures to Europe and Abbas' attitude was in marked contrast to that of his grandfather, Tahmasp I, who had expelled the English traveller Anthony Jenkinson from his court upon hearing he was a Christian.

[129] The group crossed the Caspian Sea and spent the winter in Moscow, before proceeding through Norway, Germany (where it was received by Emperor Rudolf II) to Rome where Pope Clement VIII gave the travellers a long audience.

[133] Eventually Abbas became frustrated with Spain, as he did with the Holy Roman Empire, which wanted him to make his 400,000+ Armenian subjects swear allegiance to the Pope but did not trouble to inform the shah when the Emperor Rudolf signed a peace treaty with the Ottomans.

[140] The blinding was only partially successful and the prince's followers planned to smuggle him out of the country to safety with the Mughals whose aid they would use to overthrow Abbas and install Mohammed on the throne.

"[149] Abbas was fluent in the Turkic dialect used by the Turkoman portion of the multi-ethnic Qizilbash organization, although he was equally at ease speaking Persian, which was the language of the administration and culture, of the majority of the population, as well as of the court when Isfahan became the capital under his reign (1598).

[153] Short in stature but physically strong until his health declined in his final years, Abbas could go for long periods without needing to sleep or eat and could ride great distances.

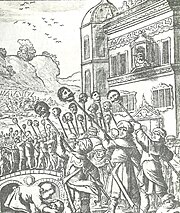

Copper engraving by Dominicus Custos , from his Atrium heroicum Caesarum pub. 1600–1602.