Abbasid Samarra

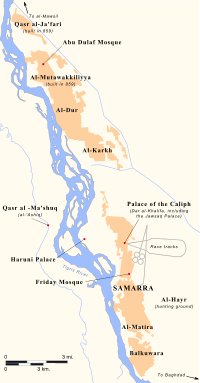

The layout of the city can still be seen via aerial photography, revealing a vast network of planned streets, houses, palaces and mosques.

Studies comparing the archeological evidence with information provided by Muslim historians have resulted in the identification of many of the toponyms within the former city.

Classical authors mention the name in various forms, including the Greek Suma (Σουμᾶ), the Latin Sumere and the Syriac Šumara.

The formal name of the Abbasid city was Surra Man Ra'ā (Arabic: سُرَّ مَنْ رَأَى), meaning "he who sees it is delighted".

These troops, who were from groups that had previously held only a marginal role in the Islamic world, were deeply unpopular among the residents of Baghdad, and violent incidents had repeatedly broken out between the soldiers and Baghdadis.

[5][6][7][8] Following a period of searching for an ideal spot, al-Mu'tasim settled on a site approximately 80 mi (130 km) north of Baghdad on the east side of the Tigris, near the head of the Nahrawan Canal.

[9][10] After sending men to buy up the local properties, including a Christian monastery, the caliph had his engineers survey the most suitable places for development.

Materials and laborers were shipped in from various parts of the Muslim world to help with the work; iron-workers, carpenters, marble sculptors and artisans all assisted in the construction.

[16] Founding a new capital was a public statement of the establishment of a new regime, while allowing the court to be "at a distance from the populace of Baghdad and protected by a new guard of foreign troops, and amid a new royal culture revolving around sprawling palatial grounds, public spectacle and a seemingly ceaseless quest for leisurely indulgence" (T. El-Hibri), an arrangement compared by Oleg Grabar to the relationship between Paris and Versailles after Louis XIV.

[9][17] In addition, by creating a new city in a previously uninhabited area, al-Mu'tasim could reward his followers with land and commercial opportunities without cost to himself and free from any constraints, unlike Baghdad with its established interest groups.

In fact, the sale of land seems to have produced considerable profit for the treasury: as Hugh Kennedy writes, it was "a sort of gigantic property speculation in which both government and its followers could expect to benefit".

[18] Al-Mutawakkil (r. 847–861) aggressively pursued new construction, extending the central city to the east and building the Great Mosque of Samarra, the cantonment of Balkuwara and numerous palaces.

[note 2] The decade following al-Mutawakkil's assassination was a turbulent period, sometimes known as the Anarchy at Samarra, during which the capital was frequently beset by palace coups and troop riots.

Al-Mutawakkil's son al-Muntasir (r. 861–862) abandoned al-Ja'fari and moved back to the Jawsaq palace, which remained the residence of his successors.

[24] Al-Muktafi (r. 902–908) at one point considered moving back to Samarra and encamped in the Jawsaq palace, but was eventually dissuaded after his advisers informed him of the high costs of the plan.

Out of 6,314 registered buildings at the site (as of 1991), only nine still have any components of significant height; the vast majority of the ruins consist of collapsed mounds of rammed earth and scattered debris.

At ground level, the remains are mostly unimpressive; when viewed from the air, however, the entire plan of the Abbasid city, with its buildings and street pattern, can clearly be seen.

[30][31][32] The core area of the city was initially constructed in the reign of al-Mu'tasim, with further development taking place under al-Wathiq and al-Mutawakkil.

Numerous army commanders, together with their regiments, were granted allotments here, including those of the Turks, Faraghina, Ushrusaniyya, Maghariba, Ishtakhaniyya, Jund, Shakiriyya, Arabs and Khurasanis.

[6][37] Besides residences, a number of other buildings were located in this area, including the public and private stables, the office of the Bureau of the Land Tax (diwan al-kharaj), and the great prison.

This site served as the official seat of government during the reigns of al-Mu'tasim, al-Muntasir, al-Musta'in, al-Mu'tazz, al-Muhtadi and al-Mu'tamid.

[55][56] During the violent period following the death of al-Mutawakkil, the Jawsaq palace is frequently mentioned as serving as a prison for prominent persons; al-Mu'tazz, al-Mu'ayyad, al-Muwaffaq, al-Muhtadi, and al-Mu'tamid all were incarcerated there at various points in time.

It was allotted to the Turkish general Ashinas, with strict orders that no strangers (i.e., non-Turks) were to be allowed to live there, and that his followers were not to associate with people of Arab culture.

The western portion of the wall bordering the central city was repeatedly demolished and rebuilt to make way for new construction, including that of the Great Mosque.

[76] Excavation work undertaken in the early 20th century revealed decorative elements consisting of stucco, frescoes, colored glass windows and niches.

[77][78][79][80] Al-Mutawakkiliyya was the largest building project of the caliph Ja'far al-Mutawakkil, who ordered the construction of a new city on the northern border of al-Dur in 859.

[85][82] The building al-Mutawakkiliyya marked the high point of the expansion of Samarra; al-Ya'qubi reports that there was continuous development between al-Ja'fari and Balkuwara, extending a length of seven farsakhs (42 km).

[97][98]Ernst Herzfeld, a German archeologist of the twentieth century, conducted a large-scale excavation at the Main Caliphal Palace of Samarra in 1911–13.

[101]Samarra first drew the attention of archeologists around the turn of the 20th century, and excavation work was conducted by Henri Viollet, Friedrich Sarre, and Ernst Herzfeld[102] in the period leading up to World War I. Aerial photographs were taken between 1924 and 1961, which preserved portions of the site that have since been overrun by new development.

[110] The Iraq War (2003–2011) also caused damage to the site, including in 2005 when a bomb was detonated at the top of the minaret of the Great Mosque.