Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan

To that end, he concluded an unfavorable truce with the reinvigorated Byzantine Empire in 689, quashed a coup attempt in Damascus by his kinsman, al-Ashdaq, the following year, and reincorporated into the army the rebellious Qaysi tribes of the Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia) in 691.

The war with Byzantium resumed, resulting in Umayyad advances into Anatolia and Armenia, the destruction of Carthage and the recapture of Kairouan, the launchpad for the later conquests of western North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, in 698.

In the east, al-Hajjaj had become Abd al-Malik's viceroy and firmly established the caliph's authority in Iraq and Khurasan, stamping out opposition by the Kharijites and the Arab tribal nobility by 702.

The foundations established by Abd al-Malik enabled his son and successor, al-Walid I (r. 705–715), who largely maintained his father's policies, to oversee the Umayyad Caliphate's territorial and economic zenith.

[6] The deaths of Yazid and his successor, his son Mu'awiya II, in relatively quick succession in 683–684 precipitated a leadership vacuum in Damascus and the consequent collapse of Umayyad authority across the Caliphate.

[24] This designation abrogated the succession arrangements reached in Jabiya, which stipulated Yazid's son Khalid would succeed Marwan, followed by another Umayyad, the former governor of Medina, Amr ibn Sa'id al-Ashdaq.

[33] Ibn Ziyad, a key figure in the establishment of Marwanid power, set about enlarging the army by recruiting widely among the Arab tribes, including those which nominally belonged to the Qays faction.

[38] In 679, a thirty-year peace treaty was concluded, obliging the Umayyads to pay an annual tribute of 3,000 gold coins, 50 horses and 50 slaves, and withdraw their troops from the forward bases they had occupied on the Byzantine coast.

[38] The modern historian Khalid Yahya Blankinship described the treaty of 689 as "an onerous and completely humiliating pact" and surmised that Abd al-Malik's ability to pay the annual tribute in addition to financing his own wartime army relied on treasury funds accrued during the campaigns of his Sufyanid predecessors and revenues from Egypt.

[47] In 689/90, Abd al-Malik used the respite from the truce to initiate a campaign against the Zubayrids of Iraq, but was forced to return to Damascus when al-Ashdaq and his loyalists abandoned the army's camp and seized control of the city.

[50] Abd al-Malik resolved to command the siege of al-Qarqisiya in person in the summer of 691, and ultimately secured the defection of Zufar and the pro-Zubayrid Qays in return for privileged positions in the Umayyad court and army.

[51] In the ensuing Battle of Maskin, most of Mus'ab's forces, many of whom were resentful at the heavy toll he had exacted on al-Mukhtar's Kufan partisans, refused to fight and his leading commander, Ibn al-Ashtar, fell at the beginning of hostilities.

— Al-Akhtal (640–708), Khaffat al-qaṭīnu ("The tribe has departed")[67] After his victory, Abd al-Malik aimed to reconcile with the Hejazi elite, including the Zubayrids and the Alids, the Umayyads' rivals within the Quraysh.

[6] Those from Kufa, in particular, had grown accustomed to the wealth and comfort of their lives at home and their reluctance to undertake lengthy campaigns far from their families was an issue that previous rulers of Iraq had consistently encountered.

[53] Concurrently, a Kharijite revolt led by Shabib ibn Yazid al-Shaybani flared up in the heart of Iraq, resulting in the rebel takeover of al-Mada'in and siege of Kufa.

[72] Al-Hajjaj responded to the unwillingness or inability of the war-weary Iraqis to face the Kharijites by obtaining from Abd al-Malik Syrian reinforcements led by Sufyan ibn al-Abrad al-Kalbi.

[81] The real casus belli, according to both Theophanes and the later Syriac sources, was Justinian's attempt to enforce his exclusive jurisdiction over Cyprus, and to move its population to Cyzicus in northwestern Anatolia, contrary to the treaty.

[72][85] The military defeats inflicted on Justinian II contributed to the downfall of the emperor and his Heraclian dynasty in 695, ushering in a 22-year period of instability, in which the Byzantine throne changed hands seven times in violent revolutions, further aiding the Arab advance.

[96] Kairouan was firmly secured as a launchpad for later conquests, while the port town of Tunis was founded and equipped with an arsenal on the orders of Abd al-Malik, who was intent on establishing a strong Arab fleet.

[94] Afterward, Hassan was dismissed by Abd al-Aziz, and replaced by Musa ibn Nusayr,[95] who went on to lead the Umayyad conquests of western North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula during the reign of al-Walid.

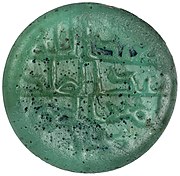

[109][110][111] He is also referred to as khalīfat Allāh (caliph of God) in a number of coins minted in the mid-690s, correspondence from his viceroy al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf and poetic verses by his contemporaries al-Akhtal, Jarir and al-Farazdaq.

[116] He maintained close ties with the Sufyanids through marital relations and official appointments, such as according Yazid I's son Khalid a prominent role in the court and army and wedding to him his daughter A'isha.

[72] At the same time, his response to the Byzantine–Christian resurgence and the criticism of Muslim religious circles, which dated from the beginning of Umayyad rule and culminated with the outbreak of the civil war, was to implement Islamization measures.

[79] In Kennedy's assessment, Abd al-Malik's "centralized, bureaucratic empire ... was in many ways an impressive achievement", but the political, economic and social divisions that developed within the Islamic community during his reign "was to prove something of a difficult inheritance for the later Umayyads".

[123] He supported al-Hajjaj's policy of collecting the poll tax, traditionally imposed on the Caliphate's non-Muslim subjects, from the mawālī of Iraq and instructed Abd al-Aziz to implement this measure in Egypt, though the latter allegedly disregarded the order.

[124] Abd al-Malik may have inaugurated several high-ranking offices, and Muslim tradition generally credits him with the organization of the barīd (postal service), whose principal purpose was to efficiently inform the caliph of developments outside of Damascus.

[125] He built and repaired roads that connected Damascus with Palestine and linked Jerusalem to its eastern and western hinterlands, as evidenced by seven milestones found throughout the region,[126][127][128] the oldest of which dates to May 692 and the latest to September 704.

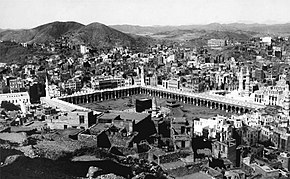

[143] According to Wellhausen, Abd al-Malik was careful not to offend his pious subjects "in the careless fashion of [Caliph] Yazid", but from the time of his accession "he subordinated everything to policy, and even exposed the Ka'ba to the danger of destruction", despite the piety of his upbringing and early career.

[147] The growing strain and heavy losses inflicted on the Syrians by the Caliphate's external enemies and increasing factional divisions within the army contributed to the weakening and downfall of Umayyad rule in 750.

[164] Abd al-Malik also married A'isha bint Musa, a granddaughter of one of Muhammad's leading companions, Talha ibn Ubayd Allah, and together they had a son, Bakkar, who was also known as Abu Bakr.