Abolitionism in the United Kingdom

[4][5][6][7] In the 17th and early 18th centuries, English Quakers and a few evangelical religious groups condemned slavery (by then applied mostly to Africans) as un-Christian.

[10] In Cartwright's Case of 1569 regarding the punishment of a slave from Russia, the court ruled that English law could not recognise slavery, as it was never established officially.

It was upheld in 1700 by Lord Chief Justice Sir John Holt when he ruled that "As soon as a man sets foot on English ground he is free".

[12][13] David Olusoga wrote of the sea change that had taken place: To fully understand how remarkable the rise of British abolitionism was, both as a political movement and as a popular sentiment, it is important to remember how few voices were raised against slavery in Britain until the last quarter of the eighteenth century.

Together with people from other nations, especially non-Christian ones, Africans were considered foreigners and thus ineligible to be English subjects; England had no naturalisation procedure.

[20] After reading about Somersett's Case, Joseph Knight, an enslaved African who had been purchased by his master John Wedderburn in Jamaica and brought to Scotland, left him.

[15] At this point the plantocracy became concerned, and got organised, setting up the London Society of West India Planters and Merchants to represent their views.

Other and dominant factors were the diminishing returns of the African slave trade itself, the bankruptcy of the West Indian sugar economy through the Haitian revolution, the interference of Napoleon and the competition of Spain.

Moreover, new fields of investment and profit were being opened to Englishmen by the consolidation of the empire in India and by the acquisition of new spheres of influence in China and elsewhere.

But the moral force they represented would have met with greater resistance had it not been working along lines favorable to English investment and colonial profit.

In 1774, influenced by the case and by the writings of Quaker abolitionist Anthony Benezet, John Wesley, the leader of the Methodist tendency in the Church of England, published Thoughts Upon Slavery, in which he passionately criticised the practice.

"[26] In 1781 the Dublin based Universal Free Debating Society challenged its members to consider if "enslaving the Negro race [is] justifiable on principles of humanity of [sic] policy?

British banks continued to finance the commodities and shipping industries in the colonies they had earlier established which still relied upon slavery, despite the legal developments in Great Britain.

Slaves cannot breathe in England; if their lungs Receive our air, that moment they are free, They touch our country and their shackles fall.

The African Association had close ties with William Wilberforce, who became known as a prominent figure in the campaign for abolition in the British Empire.

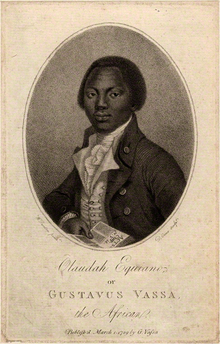

In Britain, Olaudah Equiano, whose autobiography was published in nine editions in his lifetime, campaigned tirelessly against the slave trade.

Also important were horrific images such as the famous Wedgwood anti-slavery medallion of 1787 and the engraving showing the ghastly layout of the slave ship, the Brookes.

There traders sold or exchanged the slaves for rum and sugar (in the Caribbean) and tobacco and rice (in the American South), which they took back to British ports.

Well-known abolitionists in Britain included James Ramsay, who had seen the cruelty of the trade at first hand; the Unitarian William Roscoe who courageously[clarification needed] campaigned for parliament in the port city of Liverpool for which he was briefly M.P., Granville Sharp, Thomas Clarkson, Josiah Wedgwood, who produced the "Am I Not A Man And A Brother?"

Clarkson became the group's most prominent researcher, gathering vast amounts of data and gaining first-hand accounts by interviewing sailors and former slaves at British ports such as Bristol, Liverpool and London.

[1][49] The abolitionists negotiated with chieftains in West Africa to purchase land to establish 'Freetown' – a settlement for former slaves of the British Empire (the Poor Blacks of London) and the United States.

British influence in West Africa grew through a series of negotiations with local chieftains to end trading in slaves.

In 1796, John Gabriel Stedman published the memoirs of his five-year voyage to the Dutch-controlled Surinam in South America as part of a military force sent out to subdue bosnegers, former slaves living in the interior.

Between 1808 and 1860, the Royal Navy's West Africa Squadron seized approximately 1,600 slave ships and freed 150,000 Africans who were aboard.

[56] In 1831, enslaved man Sam Sharpe led the Christmas Rebellion (Baptist War) in Jamaica, an event that catalyzed anti-slavery sentiment.

This combination of political pressure and popular uprisings convinced the British government that there was no longer any middle ground between slavery and emancipation.

Peaceful protests continued until the government passed a resolution to abolish apprenticeship and the slaves gained de facto freedom.

[61] This was because abolitionists had not planned for much more than the long-awaited reform of the law, and felt that freedom along with the option of returning to Africa to live in Freetown, or the nearby state of Liberia, was infinitely preferable to continued chattel slavery.

Deep South, which relied on slavery for cotton production, to fuel the spinning and weaving mills in Manchester and other northern cities.

London merchant banks made loans throughout the supply chain to planters, factors, warehousers, carters, shippers, spinners, weavers, and exporters.