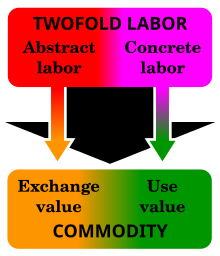

Abstract labour and concrete labour

In the introduction to his Grundrisse manuscript, Marx argued that the category of abstract labour "expresses an ancient relation existing in all social formations"; but, he continued, only in modern bourgeois society (exemplified by the United States) is abstract labour fully realized in practice.

The expansion of trade requires the ability to measure and compare all kinds of things, not just length, volume and weight, but also time itself.

Originally, the units of measurement used were taken from everyday life—the length of a finger or limb, the volume of an ordinary container, the weight one can carry, the duration of a day or a season, the number of cattle.

[8] In other words, when labour becomes a commercial object traded in the marketplace, then the form and content of work in the workplace will be transformed as well.

[9] If different products are exchanged in market trade according to specific trading ratios, Marx argues, the exchange process at the same time relates, values and commensurates the quantities of human labour expended to produce those products, regardless of whether the traders are consciously aware of that (see also value-form).

Closely related to this, is the growth of a cash economy, and Marx claims that: "In proportion as exchange bursts its local bonds, and the value of commodities more and more expands into an embodiment of human labour in the abstract, in the same proportion the character of money attaches itself to commodities that are by Nature fitted to perform the social function of a universal equivalent.

But money enables us to express and compare the value of all different labour-efforts—more or less accurately—in money-units (initially, quantities of gold, silver, or bronze).

The corvee can be measured by time in just the same way as the labour which produces commodities, but every serf knows that what he expends in the service of his lord is a specific quantity of his own personal labour-power.

... For a society of commodity producers—whose general social relation of production consists in the fact that they treat their products as commodities, hence as values, and in this business-like form bring their individual, private labours into relation with each other as homogenous human labour—Christianity with its religious cult of man in the abstract, more particularly in its bourgeois development, i.e. in Protestantism, Deism, etc., is the most fitting form of religion.

Marx's theory of alienation considers the human and social implications of the abstraction and commercialization of labour.

His concept of reification reflects about the inversions of object and subject, and of means and ends, which are involved in commodity trade.

Marx regarded the distinction between abstract and concrete labour as being among the most important innovations he contributed to the theory of economic value, and subsequently Marxian scholars have debated a great deal about its theoretical significance.

[23] They argue that the abstract treatment of human labour-time is something that evolved and developed in the course of the whole history of trade, or even precedes it, to the extent that primitive agriculture already involves attempts to economise labour, by calculating the comparative quantities of labour-time involved in producing different kinds of outputs.

In this sense, Marx argued in his book A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859) that "This abstraction, human labour in general, exists in the form of average labour which, in a given society, the average person can perform, productive expenditure of a certain amount of human muscles, nerves, brain, etc.

Generally Marx assumed that—irrespective of the price for which it is sold—skilled labour power had a higher value (it costs more to produce, in money, time, energy and resources), and that skilled work could produce a product with a higher value in the same amount of time, compared to unskilled labour.

In the first volume of Das Kapital Marx had declared his intention to write a special study of the forms of labour-compensation, but he never did so.

[32] The rent-seeking educated class, on this view, can often raise its income far beyond the real worth of its work, if they occupy a privileged position, if its specialist skills happen to be in short supply or in demand, or if they are hired through the "old boy" networks.

Marx did not think there was anything particularly mysterious about the fact that people valued products because they have to spend time working to produce them, or to buy them.

Ricardo, by a violent assumption, founded his theory of value on quantities of labour considered as one uniform thing.

He was aware that labour differs infinitely in quality and efficiency, so that each kind is more or less scarce, and is consequently paid at a higher or lower rate of wages.

I hold it to be impossible to compare a priori the productive powers of a navvy, a carpenter, an iron-puddler, a school master and a barrister.

"[35]Replying to this type of criticism, the Russian Marxist Isaak Illich Rubin argued that the concept of abstract labour was really much more complex than it seemed at first sight.

[39][40] Possibly, these conceptual issues can be resolved, through a better empirical appreciation of the political economy of education, skills and the labour market.