Abu Musab al-Zarqawi

[11][12] Raised in Zarqa, an industrial town located 27 kilometers (17 mi) north of Amman, with seven sisters and two brothers,[13] and of Bedouin background, his father has been described as either a retired army officer or a practitioner of traditional medicine whose death precipitated the economic distress of the family, pushing Zarqawi to become a street thug, known for his fights, the terror he inspired, his heavy drinking and his nickname "the Green Man" because of his many tattoos.

[11] In Pakistan he celebrated the marriage of one of his seven sisters to Abu Qudama Salih al-Hami, a Jordanian-Palestinian journalist close to the Palestinian militant Abdullah Azzam, known for "resurrecting jihad" in modern times, because he was one-legged and he thought he couldn't find a suitable partner otherwise,[24] while, years later, the same al-Hami would write a book entitled Fursan al-Farida al-Gha’iba (Knights of the Neglected Duty [of Jihad]), where he criticized Maqdisi's jihadi credentials after he parted ways with Zarqawi.

[11] On the other hand, Ahmed Hashim says that he did fight in the battles of Khost and Gardez, while the magazine, which translates as The Solid Edifice in English, was published in both Arabic and Urdu from the Hayatabad suburb of Peshawar in Pakistan, where he also met his future spiritual mentor, the influential Salafi jihadi ideologue Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi, in 1990.

[23] According to a report by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, "Zarqawi's criminal past and extreme views on takfir (accusing another Muslim of heresy and thereby justifying his killing) created major friction and distrust with bin Laden when the two first met in Afghanistan in 1999.

[28] When Pakistan revoked his visa, he crossed into Afghanistan, where he met, still according to Jordanian officials and also German court testimony, with Osama bin Laden and other al-Qaeda leaders in Kandahar and Kabul.

Jordanian court documents alleged that Zarqawi, during the summer of 2002, began training a band of fighters at a base in Syria,[45] which on October 28, 2002, shot and killed Laurence Foley, a U.S. senior administrator of U.S. Agency for International Development in Amman, Jordan.

[79] The November 2005 Amman bombings that killed sixty people in three hotels, including several officials of the Palestinian Authority and members of a Chinese defense delegation, were claimed by Zarqawi's group 'Al-Qaeda in Iraq'.

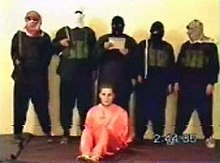

[85] In May 2004, a video appeared on an alleged al-Qaeda website showing a group of five men, their faces covered with keffiyeh or balaclavas, beheading American civilian Nicholas Berg, who had been abducted and taken hostage in Iraq weeks earlier.

[110] Tenet also wrote in his book that Thirwat Shehata and Yussef Dardiri, "assessed by a senior al-Qa'ida detainee to be among the Egyptian Islamic Jihad's best operational planners", arrived in Baghdad in May 2002 and were engaged in "sending recruits to train in Zarqawi's camps".

If you agree with us on it, if you adopt it as a program and road, and if you are convinced of the idea of fighting the sects of apostasy, we will be your readied soldiers, working under your banner, complying with your orders, and indeed swearing fealty to you publicly and in the news media, vexing the infidels and gladdening those who preach the oneness of Allah.

No sooner had the calls been cut off than Allah chose to restore them, and our most generous brothers in al-Qaeda came to understand the strategy of the Tawhid wal-Jihad organization in Iraq, the land of the two rivers and of the Caliphs, and their hearts warmed to its methods and overall mission.

In September 2005, U.S. intelligence officials said they had confiscated a long letter that al-Qaeda's deputy leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri, had written to Zarqawi, bluntly warning that Muslim public opinion was turning against him.

"[121] According to the Senate Report on Prewar Intelligence released in September 2006, "in April 2003 the CIA learned from a senior al-Qa'ida detainee that al-Zarqawi had rebuffed several efforts by bin Ladin to recruit him.

'"[122] In the April 2006 National Intelligence Estimate, declassified in September 2006, it asserts, "Al-Qa'ida, now merged with Abu Mus'ab al-Zarqawi's network, is exploiting the situation in Iraq to attract new recruits and donors and to maintain its leadership role.

Regarding Zarqawi, Powell stated that: Iraq today harbors a deadly terrorist network headed by Abu Musab Al-Zarqawi, an associate and collaborator of Osama bin Laden and his Al Qaeda lieutenants.

"[127] A Jordanian security official told The Washington Post that documents recovered after the overthrow of Saddam show that Iraqi agents detained some of Zarqawi's operatives but released them after questioning.

"[129] Counterterrorism scholar Loretta Napoleoni quotes former Jordanian parliamentarian Layth Shubaylat, a radical Islamist opposition figure,[130] who was personally acquainted with both Zarqawi and Saddam Hussein: First of all, I don't think the two ideologies go together, I'm sure the former Iraqi leadership saw no interest in contacting al-Zarqawi or al-Qaeda operatives.

According to sensitive reporting, al Zarqawi was setting up sleeper cells in Baghdad to be activated in case of a U.S. occupation of the city, suggesting his operational cooperation with the Iraqis may have deepened in recent months.

The official stated that a foreign government requested in October 2002 that the IIS locate five individuals suspected of involvement in the murder of Laurence Foley, which led to the arrest of Abu Yasim Sayyem in early 2003.

)"[142] In his book At the Center of the Storm, George Tenet writes: ... by the spring and summer of 2002, more than a dozen al-Qa'ida-affiliated extremists converged on Baghdad, with apparently no harassment on the part of the Iraqi government.

Scheuer explained, "the reasons the intelligence service got for not shooting Zarqawi was simply that the President and the National Security Council decided it was more important not to give the Europeans the impression we were gunslingers" in an effort to win support for ousting Saddam Hussein.

DeLong, however, claims that the reasons for abandoning the opportunity to take out Zarqawi's camp was that the Pentagon feared that an attack would contaminate the area with chemical weapon materials: We almost took them out three months before the Iraq war started.

We held a series of NSC meetings on that topic... Colin [Powell] and Condi [Condoleezza Rice] felt a strike on the lab would create an international firestorm and disrupt our efforts to build a coalition to confront Saddam...

However, according to a statement made the following day by Major General William Caldwell of the U.S. Army, Zarqawi survived for a short time after the bombing and, after being placed on a stretcher, attempted to move and was restrained, after which he died from his injuries.

"[196][185][197] On June 16, 2006, Abu Abdullah Rashid al-Baghdadi, the head of the Mujahideen Shura Council, which groups five Iraqi insurgent organizations including Al-Qaeda in Iraq, released an audiotape statement in which he described the death of al-Zarqawi as a "great loss".

[198] Abdelmalek Droukdel, the leader of the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC), published a statement on a website where he said: "O infidels and apostates, your joy will be brief and you will cry for a long time... we are all Zarqawi.

[202] On June 30, 2006, Osama bin Laden released an audio recording in which he stated, "Our Islamic nation was surprised to find its knight, the lion of jihad, the man of determination and will, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, killed in a shameful American raid.

Reports in The New York Times on June 8 treated the betrayal by at least one fellow Al-Qaeda member as fact, stating that an individual close to Zarqawi disclosed the identity and location of Sheikh Abu Abdul Rahman to Jordanian and American intelligence.

[208] Khalilzad, in an interview with CNN's Wolf Blitzer, had stated the bounty would not be paid because the decisive information leading to Zarqawi's whereabouts had been supplied by an al-Qaeda operative in Iraq, whose own complicity in violent acts would disqualify him from receiving payment.

In addition, the 30,000 strong U.S. troop surge supplied military planners with more manpower for operations targeting Al-Qaeda in Iraq, The Mujahadeen Shura Council, Ansar Al-Sunnah and other terrorist groups.