Achievement gaps in the United States

Achievement gaps in the United States are observed, persistent disparities in measures of educational performance among subgroups of U.S. students, especially groups defined by socioeconomic status (SES), race/ethnicity and gender.

The report found that a combination of home, community, and in-school factors affect academic performance and contribute to the achievement gap.

Attempts to minimize the achievement gap by improving equality of access to educational opportunities have been numerous but fragmented.

These efforts include establishing affirmative action, emphasizing multicultural education, and increasing interventions to improve school testing, teacher quality and accountability.

[5] Asian Americans of Indian, Chinese, Japanese, and Korean descent score the highest on average, with the difference primarily on mathematics subtests, in all scholastic standardized tests such as the SAT, GRE, MCAT, USMLE exams and IQ tests followed by White Americans who score in the intermediate range.

Researchers have not reached consensus about the causes of the academic achievement gap; instead, there exists a wide range of studies that cite an array of factors, both cultural and structural, that influence student performance in school.

Sociologist Annette Lareau suggested that students who lack middle-class cultural capital and have limited parental involvement are likely to have lower academic achievement than their better resourced peers.

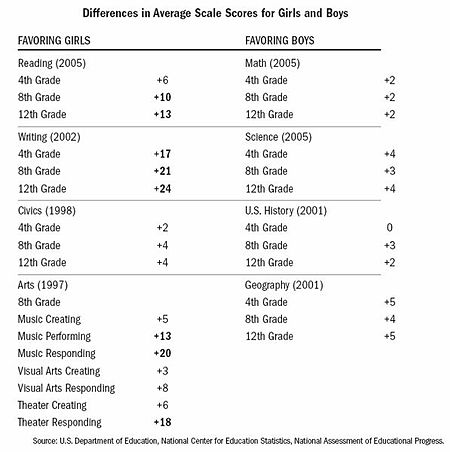

In the 1970s and 1980s, data showed girls trailing behind boys in a variety of academic performance measures, specifically in test scores in math and science.

[9] Data in the last twenty years shows the general trend of girls outperforming boys in academic achievement in terms of class grades across all subjects and college graduation rates, but boys scoring higher on standardized tests and being better represented in the higher-paying and more prestigious job fields such as STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math).

Female students generally have better grades in their math classes, and this gap starts off very minimal but increases with age.

Male students also score higher on measures of college readiness, such as the AP Calculus exams[16] and the math section of the SAT.

In 2008 Janet Hyde and others published a study showing that male and female students did equally well on No Child Left Behind standardized tests that were administered in second through eleventh grades in ten states.

However, Hyde and her team did find gaps that favored males at the upper end of the achievement distribution and tried to examine gaps on more difficult test questions (previous research has shown that males outperform females on more challenging items), but the tests they examined lacked adequately challenging items.

[35] A study by Fennema et al. has also shown that teachers tend to name males when asked to list their "best math students".

Teacher assessment evidence comes from a relatively small number of classrooms when compared to standardized tests, which are administered in every public school in all fifty states.

[38] There is speculation that gender stereotyping within classrooms can also lead to differences in academic achievement and representation for female and male students.

[41] The gender achievement gap, measured by standardized test scores, suspensions, and absences, in favor of female students, is larger at worse schools and among lower-income households.

Differences in gender roles in a particular culture, as well as sexism, can influence a person's interests, opportunities, and activities in a way that might increase or decrease intellectual abilities for any particular task.

[49] The differing maturation speed of the brain between boys and girls affects how each gender processes information and could have implications for how they perform in school.

[50] It is important to address the gender achievement gap in education because failure to cultivate the academic talents of any one group will have aggregate negative consequences.

[39] Researchers have found that the gender achievement gap has a large impact on the future career choices of high-achieving students.

[52] The term LGBT refers to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons but often is understood to encompass the sexual minority.

However, with the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network's (GLSEN) recurring study on school climate in the U.S. for LGBT students, there is now more information indicating the existence of an achievement gap.

[53] In United States secondary schools, LGBT youth often have more difficult experiences compared to their heterosexual peers, leading to observed underachievement, though current data is limited.

Students who are out, while receiving increased harassment from homophobic peers, have lower instances of depression and a greater sense of belonging, a phenomenon well documented in other LGBT studies as well.

[57] An extensive nationwide survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicates that, among women, LGBT identity is inversely related to education level, meaning that for every progressive education level, the percentage of women identifying as LGBT steadily decreases.

[62] Because of these negative home environments, the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, based on studies in Seattle, estimates that 40% of all homeless youth in the United States are LGBT, compared to roughly 3.5% of the general population.

Some public schools are either reluctant to or ignorant about enrolling homeless students, significantly thwarting a teen's pursuit of educational opportunities.

When surveyed, school personnel in California, Massachusetts, and Minnesota ranked lesson plans as the top need in addressing LGBT concerns.

Their proposed curriculum would aim to teach students, over the course of their K–12 education, to understand sexual orientation as well as gender roles, and treat others with respect, among other key concepts.