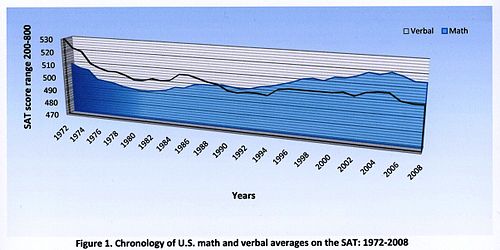

Math–verbal achievement gap

To test that hypothesis Lech constructed scores of survey instruments compiled from the math questions derived from publicly released SATs from the early 1980s through 2005.

Rothstein also suggested that the hugely successful SAT and ACT test preparation courses are unwittingly emphasizing mathematical prowess over verbal acuity.

He rationalized that successful test-taking techniques taught in these courses to boost test scores work very well for multiple-choice math questions.

[6] Rothstein also highlighted that English-language-learners (hereinafter ELL) in American schools were on the increase, and certainly that could have a downward pull on the national verbal average on these standardized tests.

It would seem likely that ELL status would adversely affect a student's verbal score to a greater extent as opposed to the mathematics portion on the same standardized test.

Finally, Rothstein indicated that studies revealed then, as they still do now, that student reading was on the decline while television-watching by American youth was on the increase.

[7][8] What Rothstein could not anticipate in 2002 is the exponential proliferation of text messages teenagers send and receive, and the potential for negative ramifications of that activity when it comes to progressing with their verbal skills.

The New York Times notes that this "phenomenon is beginning to worry physicians and psychologists, who say it is leading to anxiety, distraction in school, falling grades, repetitive stress injury and sleep deprivation."

[10] Lech's alternative suggestions for further research in that 2007 dissertation indicated that it is quite likely the math–verbal achievement gap could be partially explained by the rapid proliferation of math and science Advanced Placement courses in American high schools.

[11] He added that this effect could be multiplied if large numbers of savvy students are front-loading the math and science AP courses in high school to intentionally "bone-up" for corresponding sections on the SAT/ACT.