Acoma Pueblo

[7] Acoma has been spelled in various other ways in historical documents, including ákuma, ákomage, Acus, Acux, Aacus, Hacús, Vacus, Vsacus, Yacco, Acco, Acuca, Acogiya, Acuco, Coco, Suco, Akome, Acuo, Ako, and A’ku-me.

The isolation and location of the Pueblo has sheltered the community for more than 1,200 years as they sought protection from the raids of the neighboring Navajo and Apache peoples.

Estevanico, a slave and was the first person of African descent to explore North America, was the first non-Indian to visit Acoma and reported it to Marcos de Niza, who related the information to the viceroy of New Spain after the end of his expedition.

There was a wall of large and small stones at the top, which they could roll down without showing themselves, so that no army could possibly be strong enough to capture the village.

The encounter shows that the Acoma had clothing made of deerskin, buffalo hide, and woven cotton, as well as turquoise jewelry, domestic turkeys, bread, pine nuts, and maize.

Acoma was next visited by the Spanish 40 years later in 1581 by Fray Agustín Rodríguez and Francisco Sánchez Chamuscado, with 12 soldiers, 3 other friars, and 13 others, including Indian servants.

Espejo also noted irrigation in Acomita, the farming village in the north valley near San Jose River, which was two leagues from the mesa.

Acoma oral history does not confirm this trade but only tells of common messengers to and from the mesa and Acomita, McCartys Village, and Seama.

Zutacapan offered to meet Oñate formally in the religious kiva, which is traditionally used as the place to make sacred oaths and pledges.

However, Oñate was scared of death and in suspicious ignorance of Acoma customs refused to enter via ladder from the roof into the dark kiva chambers.

[12][16] Soon after Oñate's departure, Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá visited Acoma by himself with a dog and a horse and asked for other supplies.

[12][16] On December 1, 1598, Juan de Zaldívar, Oñate's nephew, reached Acoma with 20–30 men and peacefully traded with them and had to wait some days for their order of ground corn.

The Spanish documents do not report an attack on the women and say that the division of the men was a reaction to Zutacapan's plan to kill Zaldívar's party.

[16] On December 20, 1598, Oñate learned of Zaldívar's death and, after receiving encouraging advice from the friars, planned an attack in revenge, as well to teach a lesson to other pueblos.

The Spanish dragged a cannon through the streets, toppling adobe walls and burning most of the village, killing 800 people (decimating 20% of the 4,000 population) and imprisoning approximately 500 others.

Two other Indian men visiting Acoma at the time had their right hands cut off and were sent back to their respective Pueblos as a warning of the consequences for resisting the Spanish.

[12][17][16] On the north side of the mesa, a row of houses still retains marks from the fire started by a cannon during this Acoma War.

Forced to formally adopt Catholicism, the Acoma proceeded to practice their traditional religion in secrecy, and combined elements of both in a syncretic blend.

About 300 two- and three-story adobe buildings stand on the mesa, with exterior ladders used to access the upper levels where residents live.

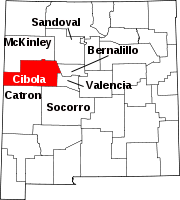

Mesas, valleys, hills, and arroyos dot the landscape that averages about 7,000 feet (2,100 m) in altitude, with about 10 inches (250 mm) of rain each year.

The Acoma later would serve as auxiliaries for forces under Spain and Mexico, fighting against raids and protecting merchants on the Santa Fe Trail.

Education was overseen by kiva headmen, who taught about human behavior, spirit and body, astrology, ethics, child psychology, oratory, history, dance, and music.

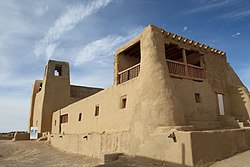

The celebration begins at San Esteban Del Rey Mission, and a carved pine effigy of Saint Stephen is removed from the altar and carried into the main plaza with people chanting, shooting rifles, and ringing steeple bells.

[24][full citation needed] In 1932, George R. Swank published a Master's thesis titled "The Ethnobotany of the Acoma and Laguna Indians," containing short sections on the Puebloans' history, culture and mythology as well as an extensive treatment of plant uses and names.

The arrival of railroads in the 1880s made the Acoma dependent on American-made goods, which suppressed traditional arts such as weaving and pottery.

They grow alfalfa, oats, wheat, chilies, corn, melon, squash, vegetables, and fruit, and they raise cattle.

The uranium mines left radiation pollution, causing the tribal fishing lake to be drained and some health problems within the community.

[3] In 2008, Pueblo Acoma opened the Sky City Cultural Center and Haak'u Museum at the base of the mesa, replacing the original, which was destroyed by fire in 2000.

The complex is also fire resistant, unlike traditional pueblos, and is painted in light pinks and purples to match the landscape surrounding it.

[3] Acoma Pueblo is open to the public by guided tour from March until October, though June and July have periods of closure for cultural activities.