Delay-line memory

To read or write a particular memory address, it is necessary to wait for the signal representing its value to circulate through the delay line into the electronics.

The basic concept of the delay line originated with World War II radar research, as a system to reduce clutter from reflections from the ground and other non-moving objects.

Several different types of delay systems were invented for this purpose, with one common principle being that the information was stored acoustically in a medium.

The Japanese deployed a system consisting of a quartz element with a powdered glass coating that reduced surface waves that interfered with proper reception.

The United States Naval Research Laboratory used steel rods wrapped into a helix, but this was useful only for low frequencies under 1 MHz.

[2] The first practical de-cluttering system based on the concept was developed by J. Presper Eckert at the University of Pennsylvania's Moore School of Electrical Engineering.

One problem with practical development was the lack of a suitable memory device, and Eckert's work on the radar delays gave him a major advantage over other researchers in this regard.

Conventional computers have a clock period needed to complete an operation, which typically start and end with reading or writing memory.

The high speed of sound in mercury (1450 m/s) meant that the time needed to wait for a pulse to arrive at the receiving end was less than it would have been with a slower medium, such as air (343.2 m/s), but it also meant that the total number of pulses that could be stored in any reasonably sized column of mercury was limited.

The system heated the mercury to a uniform above-room temperature setting of 40 °C (104 °F), which made servicing the tubes hot and uncomfortable work.

(Alan Turing proposed the use of gin as an ultrasonic delay medium, claiming that it had the necessary acoustic properties.

Some mercury delay-line memory devices produced audible sounds, which were described as akin to a human voice mumbling.

When bits from the computer entered the magnets, the nickel would contract or expand (based on the polarity) and twist the end of the wire.

Delay-line memory was far less expensive and far more reliable per bit than flip-flops made from tubes, and yet far faster than a latching relay.

A similar solution to the magnetostrictive system was to use delay lines made entirely of a piezoelectric material, typically quartz.

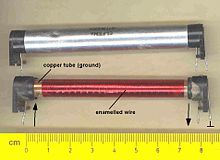

They consist of a long electric line or are made of discrete inductors and capacitors arranged in a chain.

To shorten the total length of the line, it can be wound around a metal tube, getting some more capacitance against ground and also more inductance due to the wire windings, which are lying close together.

[7] Both digital and analog methods are bandwidth limited at the upper end to the half of the clock frequency, which determines the steps of transportation.

This is remedied by making all conductor paths of similar length, delaying the arrival time for what would otherwise be shorter travel distances by using zig-zagging traces.